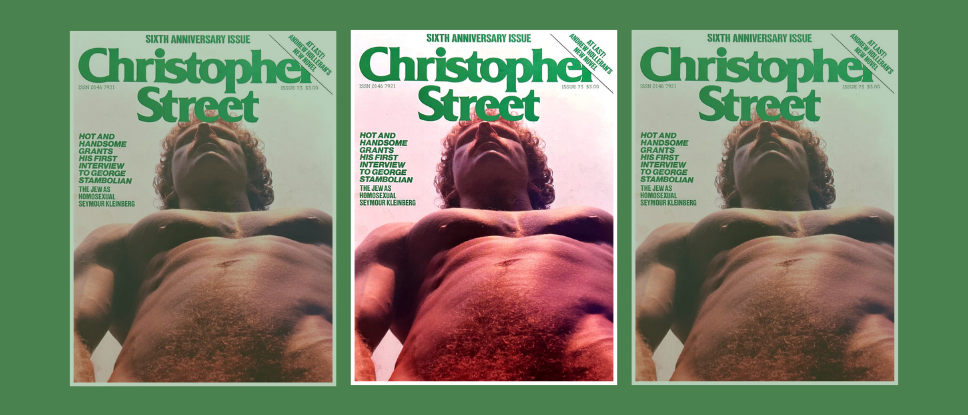

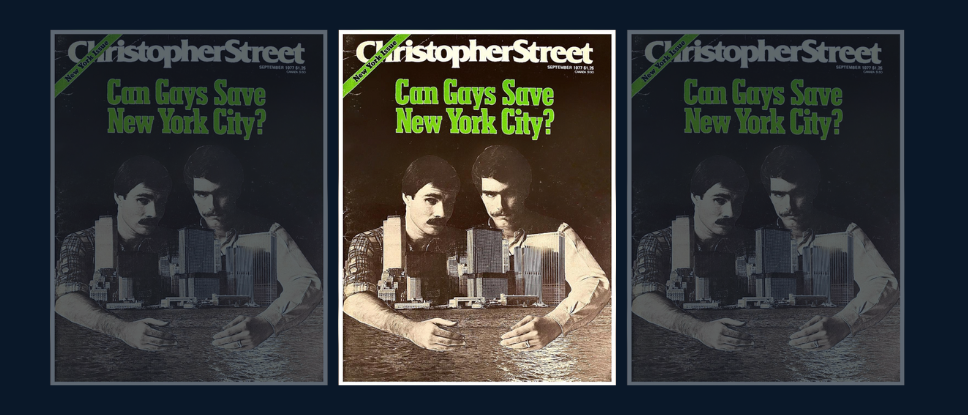

This introduction by Christopher Street editor Michael Denneny (1943-2023) appeared in The Christopher Street Reader, a collection of writings from the magazine, in 1983. It provides a helpful introduction to Christopher Street's philosophy and its desire to create a gay public sphere.

Since the 17th century, magazines have been a peculiarly modern device for bringing a public space into existence. Like a town meeting, a magazine enables people to be in each other’s company by sharing talk about matters that concern them. And it is through talking with others that most of us start to make some sense out of the world, and begin to discover who we are and what we think. Such talk usually does not lead toward general agreement but, paradoxically, to even greater diversity of opinion. Only people who don’t talk to each other—or don’t do it well—think they agree. In my experience, the better and longer the talk, the more you find yourself in disagreement with others, and, if the discussion has genuine quality, eventually in disagreement with yourself—at which point it gets interesting, for this is when change becomes possible and things begin to happen.

Publishing a magazine, writing for a magazine, subscribing to and supporting a magazine are all aspects of an activity whose final purpose is not general agreement, a party line, but rather a greater ease and sureness in moving in the world, a firmer grasp of who we are and what we think. Christopher Street has never tried to develop a party line; we always thought our task was to open a space, a forum, where the developing gay culture could manifest and experience itself. For people who have been excluded from the social world—gays, blacks, women, any minority group that has been colonized by a dominating culture—this access to public space is basic and urgent. Gays know, or should know, as well and colonized people the cost of being “invisible men.” We’re intimately aware of “the havoc wrought in the souls of people who aren’t supposed to exist” (Ntozake Shange). This is no benign neglect, it is an active assault against our persons, a total public denial of the validity of our lives as we experience them. The gap between our inner lives and the socially acceptable version of reality is so wide it makes existence into a charade. It makes you dizzy. It makes you wonder if you’re really there.

This experience of displacement and insubstantiality is common to all people society forces to be invisible. The dizziness of the dizzy queen not only expresses the inner confusion of finding oneself constantly forced to play in a charade—“Am I real, honey? Is this world for real?”—it is also a stubborn, insidious, perhaps unconscious but quite effective political assertion—“Don’t you dare think I’m really here, that this is really real, that this is who I am.” The celebrated ambiguity of camp is a psychological zap, guerrilla tactics for people who can’t afford open warfare—not unlike the legendary laziness of blacks or stupidity of colonized people. Straights are irritated or uncomfortable with it because it’s meant to make them irritated or uncomfortable—if you’re going to press us down with those values, we’re going to camp it up and undermine those values, ridicule them and expose them for the pretensions they are. Those reactionaries who in their heart of hearts know we’re making a mockery of them are right on this point. You bet. When you can’t afford to fight back openly, you ridicule, you undermine, you resist in the only way you can.

But the cost is too high. Living in the closet and putting on a mask when you go into the world does not leave your soul intact. Social invisibility reaches inward and causes a confusion of spirit. Our imaginations become closeted internally—a phenomenon feminists are pointing to when they discuss “male identified women.” We are no longer able to imagine our own lives. It’s well known that we come out sexually before we come out socially, that most of us have been screwing for years before we’re willing to say to ourselves, never mind publicly, “I’m gay.” After all, homosexuals were undoubtedly sexually active before Stonewall as well as after. But the assertion of gay liberation that started with the Stonewall riot is not enough. Pecs, track lighting, and brunch do not a soul make. We all know people who dress like clones—and whether they know it or not, this is a militant act, broadcasting the statement “I am gay” not only to gays (we could always recognize each other) but primarily to the straight world—but these same clones wouldn’t be caught dead reading a gay book or subscribing to a gay magazine.

This seems to me an enormous strategic mistake. (Of course, being deeply involved in the business of gay books and magazines, I’m not exactly an impartial commentator—on the other hand, who is?) Put simply, I don’t think it’s possible to have a liberated gay world socially or a satisfying and fulfilling gay life individually without developing a gay culture. Over a decade ago, we found that a private gay life was not enough, that we required some kind of public and visible assertion of our gayness, that “coming out” was the path to liberation and the “closet” a repressive trap, not only politically but in terms of our immediate day-to-day lives. While we may be obscure about the precise nature of this connection, unable even to our own satisfaction to articulate why we feel the necessity of this public assertion—which, quite honestly, most straights and not a few gays still view as a perverse flaunting of our lifestyle—still, in our gut we knew it was necessary, and this obscure but quite powerful conviction is what has fueled the gay movement for the last ten years.

It is as if liberation proceeds in three stages. The first is the sheer exhilarating discovery of sex and same-sex emotional bonding, which becomes the true center of our lives and the ultimate excitement of our souls even if we remain socially in the closet. The second stage is the public and social assertion of our gayness; our demand for the rights and dignity that a decent respect for humanity in all its diversity would grant to everyone. To these, I suggest, should be added a third stage, the liberation of our imaginations from the closet of straight culture. We need to be able to imagine our own lives as we live them if we are to have any chance of living them well. To use a concrete example: for many years I used the term “ex-lover” to name relationships I thought had ended, had failed. It took forever before I woke up to the patent fact that I spent a substantial part of my social time with these “ex” lovers; that these were among the deepest, closest, most stable and rewarding relationships I had. When I looked around and saw this was increasingly the case with many of my friends, it began to dawn on me that we were in the process of redefining the family, or better still, that we were creating new structures—little tribes—that functioned in our lives in much the same way as, and perhaps in place of, the traditional family. For me this incident encapsulates a general phenomenon: we are in the odd position of having trouble seeing the very lives we lead because we still look at them through the lenses of straight culture, the same straight culture that has gone to such bizarre efforts to deny that we even exist.

Anyone today who thinks he can lead a free gay life without participating in the creation of gay culture is in the same position as those homosexuals of the fifties and sixties who thought they could have meaningful and significant intimate relationships while staying in the closet. It won’t work. It didn’t work then. Untold numbers of homosexuals were severely damaged or driven to distraction by this contradiction beatween their intimate and their public lives—a situation brilliantly captured by The Boys in the Band, an analysis of an emotional pre-revolutionary situation if I’ve ever seen one. The only way to consolidate the gains of the past decade of gay liberation is to forge a new imagination of our lives and the world, and this can only be done by a serious interaction with our writers and artists, for these after all are the people who have elected the task of reporting and imagining and celebrating and criticizing how we live now.

I suppose it’s necessary to add that a commitment to a separate gay culture and identity in no way requires the rejection of straight culture. Does anybody think that a Jew who gains sustenance and identity from his people’s heritage cannot also be an American; that someone deeply involved in the forging of an American black culture cannot love Shakespeare and Cézanne? The idea is absurd and is never raised with other groups; when it comes up in discussions of gay culture, in attacks on what’s called gay separatism, it’s a red herring.

The writings included in this book are among the most interesting and valuable attempts I know at imagining our lives anew. These writers do not agree with one another. They are pushing and probing, thinking and criticizing, celebrating and berating the new lives we find ourselves leading and the new people we have become. To the reader who takes them seriously, they offer invaluable and concrete assistance in the daily struggle we all face to invent ourselves anew, and to recognize ourselves when we’ve done it.

❡

Any collection of articles from a magazine presents the opportunity for, in fact requires, a reflective interpretation of what exactly that magazine is all about. In re-reading five years of published material inevitably one begins to see the collective endeavor in the clearer light of hindsight. In the case of Christopher Street, my own experience of this massive re-reading left me—a bit to my surprise—with a new sense of a roughly coherent public discussion with its own logic and progression. It is this rough sense of the unfolding of an ongoing discussion that informs the present collection, its content and arrangement.

This coherence should not be overemphasized. A magazine publishes articles—glimpses of how we are, brief and tentative surveys of the geography of our lives, sudden clearings of self-awareness, reports from different corners of our world—and a collection of such articles could never offer a systematic and balanced overview. The vagaries of interest, accidents of timing and pressures of circumstance, financial and otherwise, see to that. Yet it did seem to us that an unusual number of articles retained their interest and vitality, that even this scattered record of the attempts of a large and open-ended group of people to make sense of their lives and confront the problems and paradoxes of establishing a gay culture was coherent enough to warrant the permanence of a book.

The final decisions on the contents and arrangement of this collection reflect our sense of the cultural evolution this magazine has recorded and reflected back to the public.

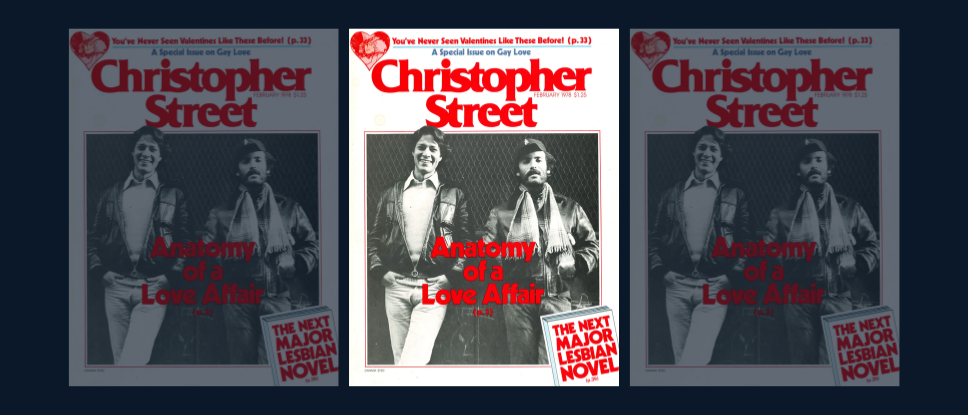

The most striking aspect of this book for regular readers of Christopher Street will undoubtedly be the absence of women. From the first issue until today, Christopher Street has not only published but gone out of its way to publish articles, fiction, art and poetry by and interviews with women writers, both lesbian and non-lesbian, including Bertha Harris, Kate Millett, Rita Mae Brown, Ntozake Shange, Audre Lord, Blanche Boyd, Mary Daly, Joan Baez, Sheila Ortiz Taylor, Noretta Koertge, Jane Rule, Olga Broumas, and Nicole Hollander among others. Yet in reading it all over, it became apparent that this was a secondary aspect of the magazine. The initial selection of material for this book included articles by some nine women and about sixty men which, sensibly enough, made us all nervous, especially since a third of those women were not gay. It would be easy to charge the magazine with tokenism and this collection with chauvinism—and we shall no doubt hear such charges—but I think the truth of the matter is more complex, less hostile, and ultimately promising.

Christopher Street started with a determined effort at gender parity which lasted about a year and a half. It would be superfluous to recount the demise of this effort—virtually everyone who has been active in any gay endeavor will be familiar with the scenario. What I personally remember with striking clarity was the time one of the women editors told me she actually didn’t read any of the pieces by men. She preferred to concentrate her work, energy, and enthusiasm on developing women writers; she simply wasn’t particularly interested in what men had to say, unless it touched on a feminist concern. I was startled because I generally found the writing of the women so interesting myself. In fact, we found it to be more or less the case that male readers were quite interested and enthusiastic about women writers, but that women had little interest in the work of the men. Their concern was so intensely engaged in the situation of women that reading the articles by men seemed irrelevant to them. So the magazine was, by and large, never able to win the loyalty of women readers, and the women on the staff slowly drifted away.

At the time all this led to some muttered sound and muted fury and hurt feelings on both sides, but it makes more sense to me now. The connection between gay men and gay women was only ideological; we did not really share a world in common. Women needed their own space, as the lesbian feminists correctly argued, and gay men were trying to create a cultural space to begin with (without the great initial advantage gay women had in the very fact of the feminist movement). The attempt at integration may or may not have been misguided, but it certainly came too soon. Both gay men and lesbians were still struggling to gain some sense of their own identity and apparently neither could afford the effort to try to make themselves acceptable to or even understood by the other.

Where it will all end up is another matter. The relation between lesbians and straight feminists may be changing, the relation between gay men and the feminist movement is certainly changing, and the relation between gay women and gay men seems to be in flux. We can all be good allies with anyone who is on our side, but we cannot be good allies, or even good friends, if we confuse ourselves with each other. We need our separate identities and we need to respect the differences between us. Personally I think that gay men can greatly benefit from reading the several excellent collections like this one, consisting entirely of the work of gay women, which are now available. But to have a few women represented in a dominantly male collection does seem objectionable to me. Christopher Street simply has to accept the fact that at the moment it is a gay male magazine; as such, it will continue to publish the best women writers we can find who will interest our readers. Before I’m attacked in print for all this, I would urge people to consider whether any feminist or lesbian magazine has ever opened its pages to as many gay men as Christopher Street has consistently to gay women—much to its benefit.

Lesbians and gay men have a lot in common, but we’re not the same folk. This would seem to be a very simple fact, one that has been abundantly clear for years. Yet confusion over this issue and the attempt to wring from the word “gay” a uniformity that would cover both men and women has led to unbelievable wrangling. It’s time to accept our differences with good humor and a genuine interest in each other’s lives and work. Lesbians and gay men are natural allies, if only because a generally hostile society sees us as the same—homosexuals. But only if we recognize our differences and can live with the same tolerance of diversity we’re demanding of straight society will we be able to work together and enjoy each other’s company. ❡