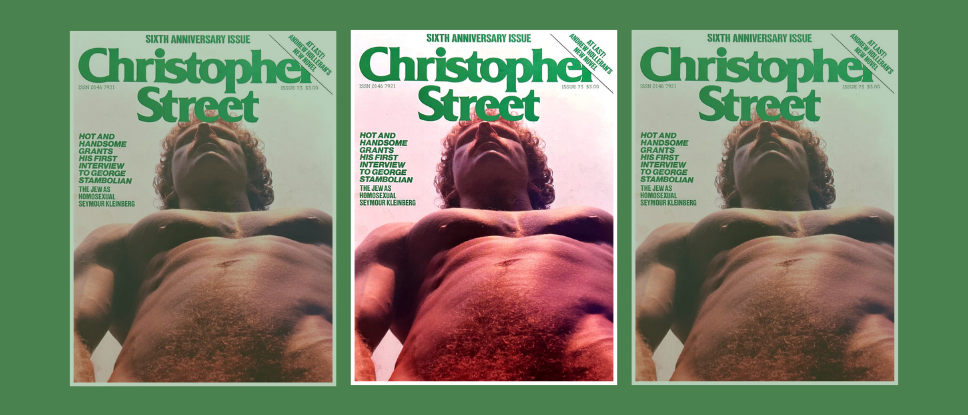

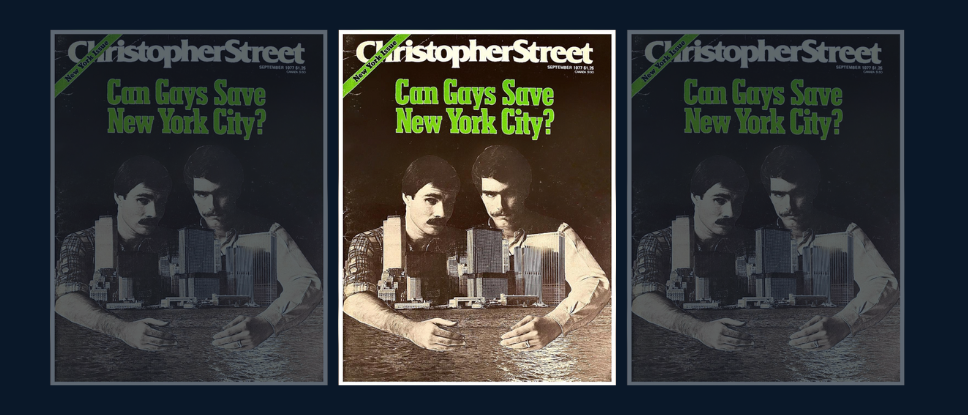

This article originally appeared in the March 1980 issue of Christopher Street on pages 14-22.

Sam Hardison is owner and director of New York’s Robert Samuel Gallery, 795 Broadway (between 10th and 11th Streets). Since its first exhibition in November 1978, it has become the leading gallery in the city specializing in male-image art.

George Stambolian, professor of French and comparative literature at Wellesley College, is co-editor of Homosexualities and French Literature, recently published by Cornell University Press.

George Stambolian: Let’s start with a definition. What do you mean by the male image in art?

Sam Hardison: I mean dealing with the male image as a very human and sensual product in the sense that we have dealt with the female image. There was a point one hundred or so years ago when a nude all of a sudden meant the female nude. The male nude ceased to be considered as a value. We’ve explored the female nude and the female image in all its aspects. Now we have to explore the male image in terms of its own qualities. The male nude is going to be a good percentage of this art because it has been the most repressed form, but the male image itself has also been repressed.

You’ve said that before opening your gallery you repeatedly received discouraging advice from other gallery owners who told you that male-image art does not sell and that, in any case, it isn’t of very good quality. I know you did considerable investigation until you found that there was in fact enough painting, drawing, and especially photography of high quality to justify and sustain a specialized gallery.

I might add that a lot of that negative advice came from gay men who run galleries that can deal with the figure, but who will not touch the male image because of fear of association.

That’s not surprising. The taboo is so great that women working in this area are considered perverse, and men are considered gay. That attitude covers not only the artist, but also the person who sells the art, and the critic who writes it. It’s the familiar Catch-22 situation: negative conditions are created and then used to justify their perpetuation. The presence of psychological fear or social pressure is particularly hard to weed out in criticism, because it is so often disguised by being offered as a purely aesthetic judgment.

That’s a very important point. There have been exhibitions on the male nude so poorly selected and presented that, if I had been a critic, I would have shown little enthusiasm for them. But there has also been a lot of negative criticism that can be understood only by seeing it as influenced by fear.

The problem goes beyond homophobia, of course. In The Male Nude (Paddington Press Ltd., 1978), Margaret Walters says that there is still a rigid distinction in our society between the sexes that has lasted and the sex that is looked at. So showing the male body as something to be looked at is a very disturbing thing for most people, men and women. The fact that gay men have been historically less disturbed by this situation is probably one explanation for their prominence as artists and models in male-image art. But the repression is real, and it affects everyone. Because of her nude photographs of her son and husband, Jacqueline Livingston is right now involved in a suit over the loss of her job at Cornell. She is also being investigated for child abuse. It’s a terribly difficult situation.

On top of everything else, she’s an extraordinarily fine photographer, and it is amazing to realize how many doors have been slammed in her face.

A little history would be helpful here. You recently had an exhibition on male-image art of the Thirties, Forties, and Fifties that included, among others, works by Paul Cadmus, Jared French, Pavel Tchelitchew, George Platt Lynes, and George Tooker. I believe these men were all gay. What kinds of difficulties did they have showing their art or having it accepted?

I never knew Tchelitchew, who’s dead now, and until I opened the gallery I was not aware of the degree to which he explored male nudes and particularly the sexuality of men relating to men. The only people who knew were his friends and some collectors. These works have rarely been exhibited. Most people only know The Tree of Life, which the Museum of Modern Art has, and other, similar works. Then I began to find pieces from old friends of his, and I was astounded by what this man had done. I’m currently putting together an exhibition of his male-image and male-nude works.

What about Cadmus and Lynes?

Lynes is also dead. He was the fashion photographer for Vogue and also did celebrity photographs in Hollywood. All through the Thirties and Forties he did a lot of male nudes, but they were collected mostly by his friends and models. You look at them now, and you see that they are certainly fine photographs and relatively reserved. I have never seen anything that Lynes did that could be labeled pornographic. But it was Cadmus who hit the prejudice head-on. His first exhibition in Washington in the Thirties included a painting called The Fleet’s In!, which caused quite a stir. Naval officials succeeded in having it removed. The painting showed sailors and prostitutes in Central Park and dealt quite explicitly with male sexuality. Paul is a fabulous man, and I have the greatest respect for him, but he’s been so bombarded over the years that he’s not aware of how much he’s been suppressed. I think he really feels that it’s not his work with male nudes so much that hindered his acceptance as an artist, but that maybe he was not as good as some of the other people around.

So here again prejudice has turned into self-doubt.

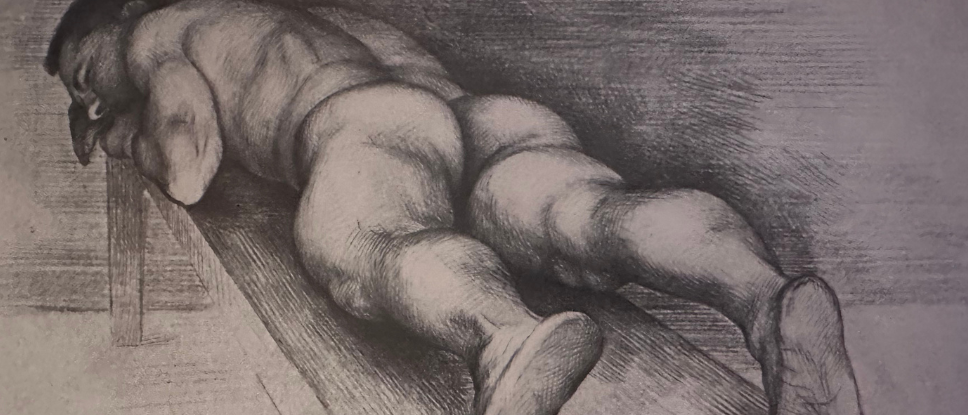

That’s a problem with most of the men we’re talking about. The first male-image piece I bought in New York was an exceptionally fine drawing of a male nude by Jared French. But Jerry has not dealt well with his work, and he doesn’t see himself as being that much of a homoerotic artist, which he is.

Do you think he would call his work homoerotic if he belonged to today’s generation?

I think so, but I don’t know him well enough to say.

It seems evident that artists like Cadmus and French were formed by their own time and generation, and that they still reflect the public attitudes of their time.

Paul Cadmus did stick to his guns. He continued to do drawings of male dancers and a lot of male nudes, and they were shown and sold, probably to a select group of gay men. But Paul did reach straight collectors and museums, thanks especially to the support of Midtown Galleries.

What has his reaction been to your gallery?

When I first opened with the Man to Man exhibition, Paul came in and introduced himself. We talked about the gallery and the show, and he was very pleasant, but to be honest I think he thought I was insane. You have to remember that up until the Leslie-Lohman Gallery, which was very much of a breakthrough because they did deal with male nudes and gay art, the male image had surfaced very rarely in New York and only in the shows of established artists like Bacon, Hockney, and Samaras.

What has to yield is the anti-representational stance so long maintained by art critics and gallery owners. Not only has the whole school of the abstract been against this kind of representational art, but there’s also been a negative attitude toward the expression of identifiable emotions. Even in photography there’s a certain modernist tradition that tends to favor banal subjects because they supposedly reveal more clearly a photographic way of seeing.

There’s no question about that. When Paul Cadmus came of age with his work, the abstract expressionists stole the show. Even when Pop Art came in and did deal with something that was representational, it looked back at traditional representational work as being very passé.

Do you feel that we’ve entered a period when we’re not going to be dominated by one particular school?

I hope so. I think that people who control the art world—gallery directors and museums—have been looking very desperately for a new movement. The new movement may be photography, and if it is, that may be a very healthy sign. It means that work dealing with the figure will have a chance to resurface.

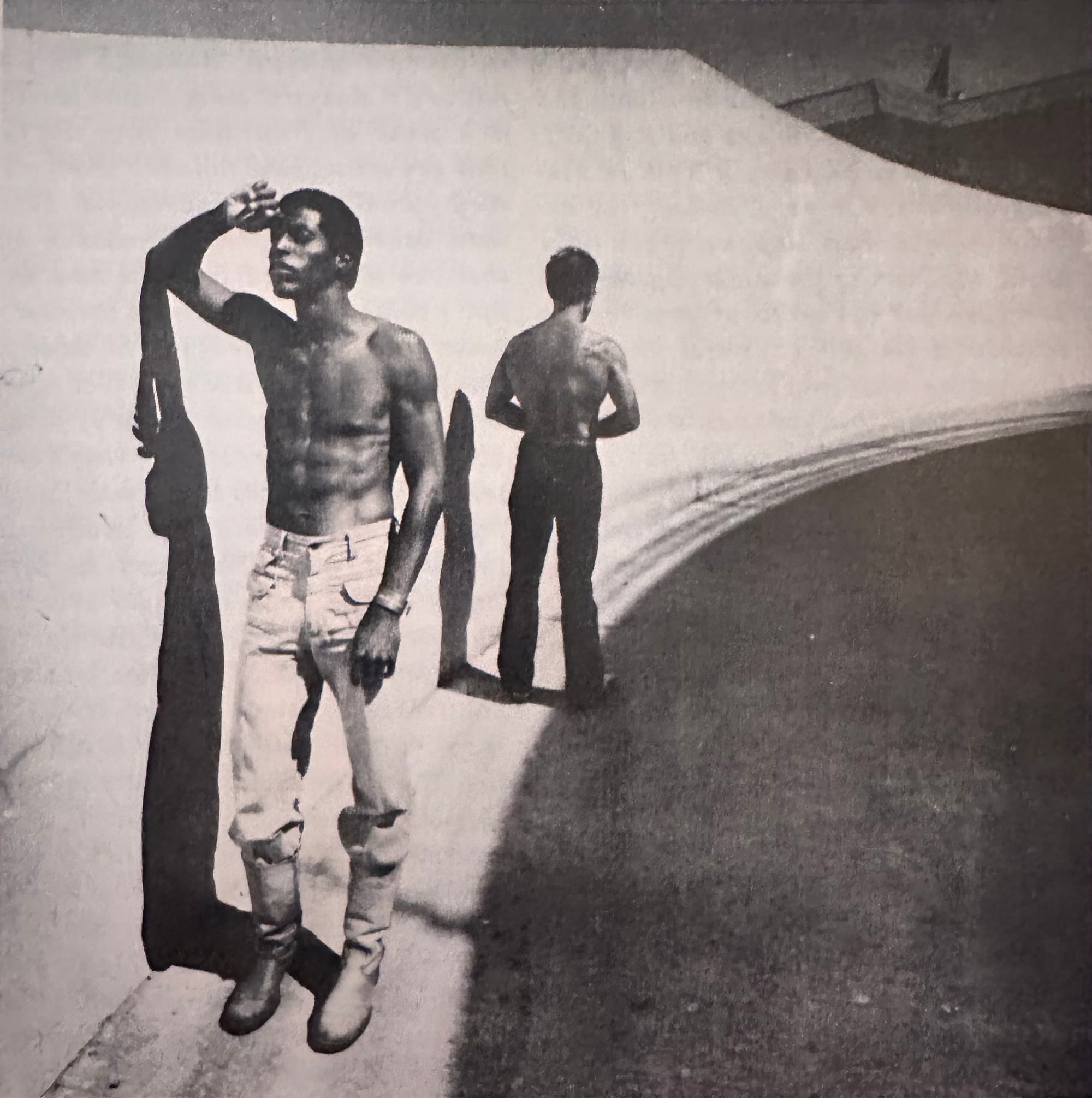

My impression is that, at least until now, the homoerotic aspect has tended to dominate the work shown at your gallery. Others might say simply that the sexual has dominated. I don’t think you can show a male nude—no matter how stylized the pose—without it being considered sexual. Anything that draws attention to a man’s body, even clothed, is also going to be seen that way. Also, at this point in history the very act of photographing or painting a man’s body makes a sexual statement no matter what other statement is being made. Obviously, the same things can be said about looking at a female body, and thanks to the work of feminist critics in particular, we’ve begun to understand the politics of figurative art in all its forms. But the fact remains that the female body has been so culturally absorbed that it doesn’t act so violently on our senses. Having said that, everything else gets terribly complicated, because there are so many degrees of quality and different ways of seeing.

I see a lot of work, an average of twenty artists’ work a week, and to a point I don’t see the shows I have as being as sexual as some people do. I agree there is a tendency to judge a work as sexual because it is a male nude, and because we’re not accustomed to looking at male nudes. I also think that it may not be completely accurate when some gay men say my shows are homoerotic, because most women who come in don’t judge the pieces as gay art at all.

But the majority of gay men do, and that’s one reason why your openings have become rather remarkable events in themselves. A special, and perhaps ideal, context for viewing is created when a group of gay men assembled to look at gay art. A friend of mine has even said that openings at your gallery, or at Stompers or Leslie-Lohman, are becoming another gay institution. So, there are the bars, the baths, CR groups, and gallery openings!

That’s interesting.

I’m not talking about cruising or therapy, but about sharing a culture by looking at works that tell us something, whether positive or negative, about our identity and purpose. That to me is very exciting. Now I wonder whether the electricity and sense of election would be there if the audience were more mixed.

The Robert Mapplethorpe opening in November attracted the most mixed audience we’ve ever had, and the electricity was definitely there. We’re picking up good support from the straight public. One test will come in September–October 1980, when we’ll have an exhibition of works by twenty-three women. So, we’ll have a mixed audience looking at male nudes by women artists.

Do you think that the gay audience you have now is the gay contingent of the existing uptown or Soho gallery audience, or is this a relatively new gay public?

It’s both. Some may have gone to galleries but not to openings. I also think we’re getting people who would never have supported a gallery before because they didn’t have a way of relating to it. But we are also getting art collectors. I do know that we must grow and expand, and that we must make art that deals with the male nude, be it gay or straight art, acceptable to the general public.

Would a change in the public affect the kind of art that is being done? In other words, to what extent is the male-image art of Mapplethorpe, Tress, or Sable directed toward an audience they sense is primarily gay?

Let’s take Kas Sable’s exhibition. A gay man going to that exhibition would call it gay art, yet a number of the pieces were sold to straight collectors and museums, who didn’t see it as gay art. This is where something is going on that I find very exciting.

Do you mean that in a Sable piece the image of a man lying on his stomach and surrounded by props like inhalers, leather boots, and high-heeled shoes is not going to seem gay to a straight audience?

No, that audience is going to see the image and those objects as sexual. For example, a woman could see the shoe not as his, but as hers.

But if women read those signs in a different way, gay men may never fully understand their experience, since we would find it difficult not to read the same signs as part of a gay iconography.

Most women who come in are aware of the fact that there is a lot of gay art in the gallery. But what is important is that they are seeing aspects of male sexuality that they have never seen in an art form before. The Arthur Tress exhibition also attracted a wide audience, although it is true that almost every piece sold went to a gay buyer. And I must say that that was the first exhibition where you really did get a sense of gay pride.

Here’s where more complications come in, because Arthur Tress makes a point of saying that his work cannot just be called gay. He is certainly using many of the elements and signs of contemporary gay culture—items of clothing, gestures, expressions, props, and places—but he is transforming the specifically gay meaning of these signs and playing with them in order to build them into something else—fantasies or states of being that extend beyond the limits of the homoerotic. Now for me, seeing and enjoying the transformation itself is what is most interesting, and that can’t happen unless one recognizes the original context of the signs. But calling the works gay can be dangerous if it denies or ignores the transformation. Gays are expert readers of some signs, but that same ability can also blind us to other signs and narrow our vision. A few gay elements don’t make everything gay.

There’s no question that our vision has been drastically narrowed. But the most important thing is what restrictions have been placed on the male image for everybody. It’s absolutely frightening when you think of what happened to the male nude in art. Look, we can do anything in art now and it’s accepted. Christo, whose work I respect, can do a running fence across California, but what is not accepted is one of the basic structures on which we’ve learned to build our art—the male nude. Many gay men do immediately assume that a male nude is gay art, but we’ve shown works by straight men, and the women’s show will include two very interesting pieces by gay women. I believe very firmly that a lot of the exhibitions we’ve had were not as gay-oriented as some people seem to think they were. Now that the male image is being explored in other areas—advertising, for example—we are all beginning to accept it. And maybe we can accept it as not being necessarily homosexual. I think that would be a very healthy thing.

But there is something in all this that is not limited to the art scene, and that is the desire of many gays to shape and maintain a specifically gay identity. So when “our” clothes or “our” disco become popularized we feel pride, but we also have a sense of loss.

There are going to be galleries, I hope, like Leslie-Lohman, Stompers, Rob of Amsterdam, that are going to deal with that which is very specifically homoerotic art. But this is not what I want to do, because I think that before you can get to the level of even dealing with that art, you’ve got to at least open the doors to male-image art. You’ve got to make that as acceptable as dealing with the female image would be. Ideally, I want my gallery to be open to as vast an audience as possible.

Is that only a commercial consideration, or is it philosophical as well?

It is very much philosophical. To be very honest, I think I could be more commercially successful if I came out as a gay gallery for gay artists. But the problem I’m dealing with is the male image. That’s a big problem, a big taboo. It has ruined a lot of artists’ lives.

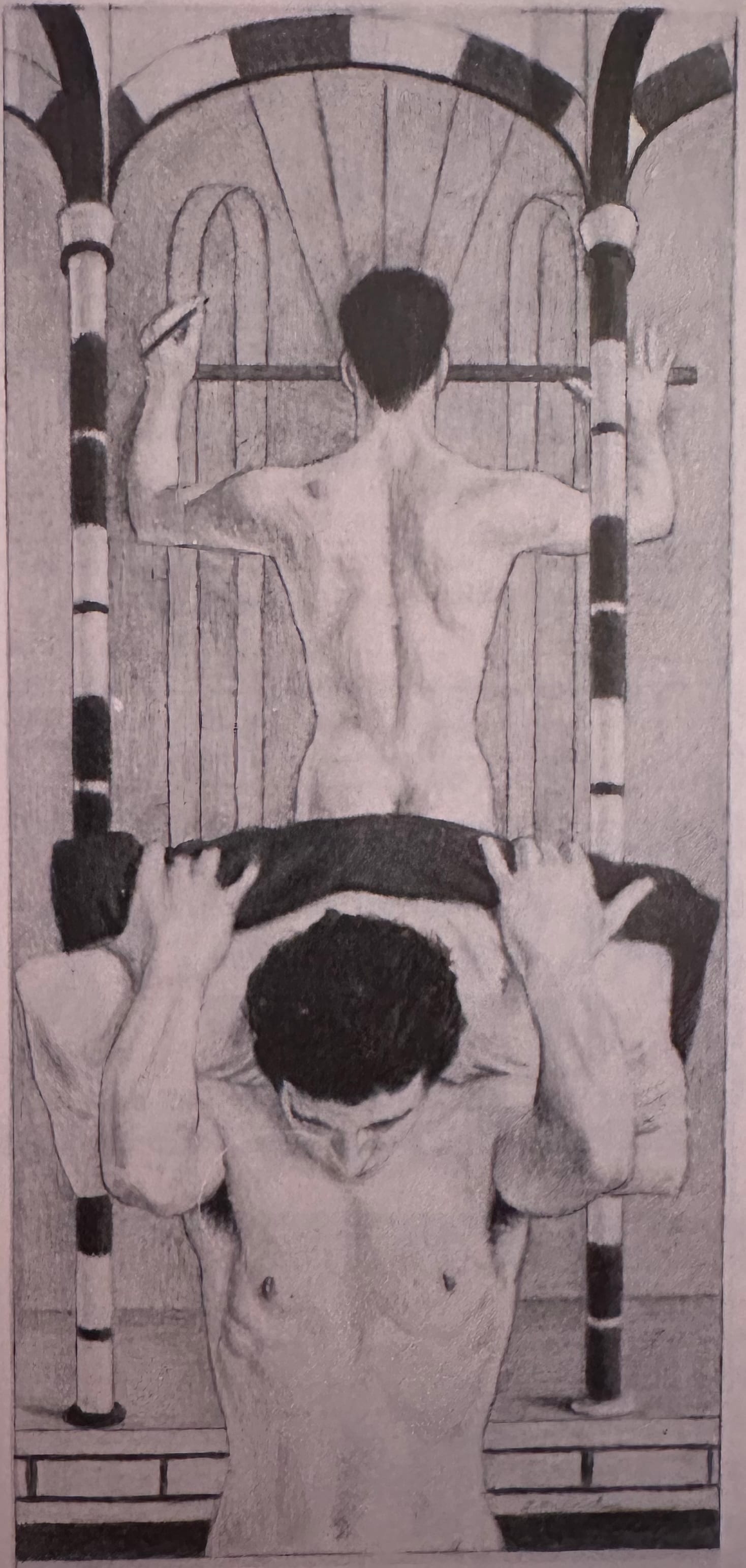

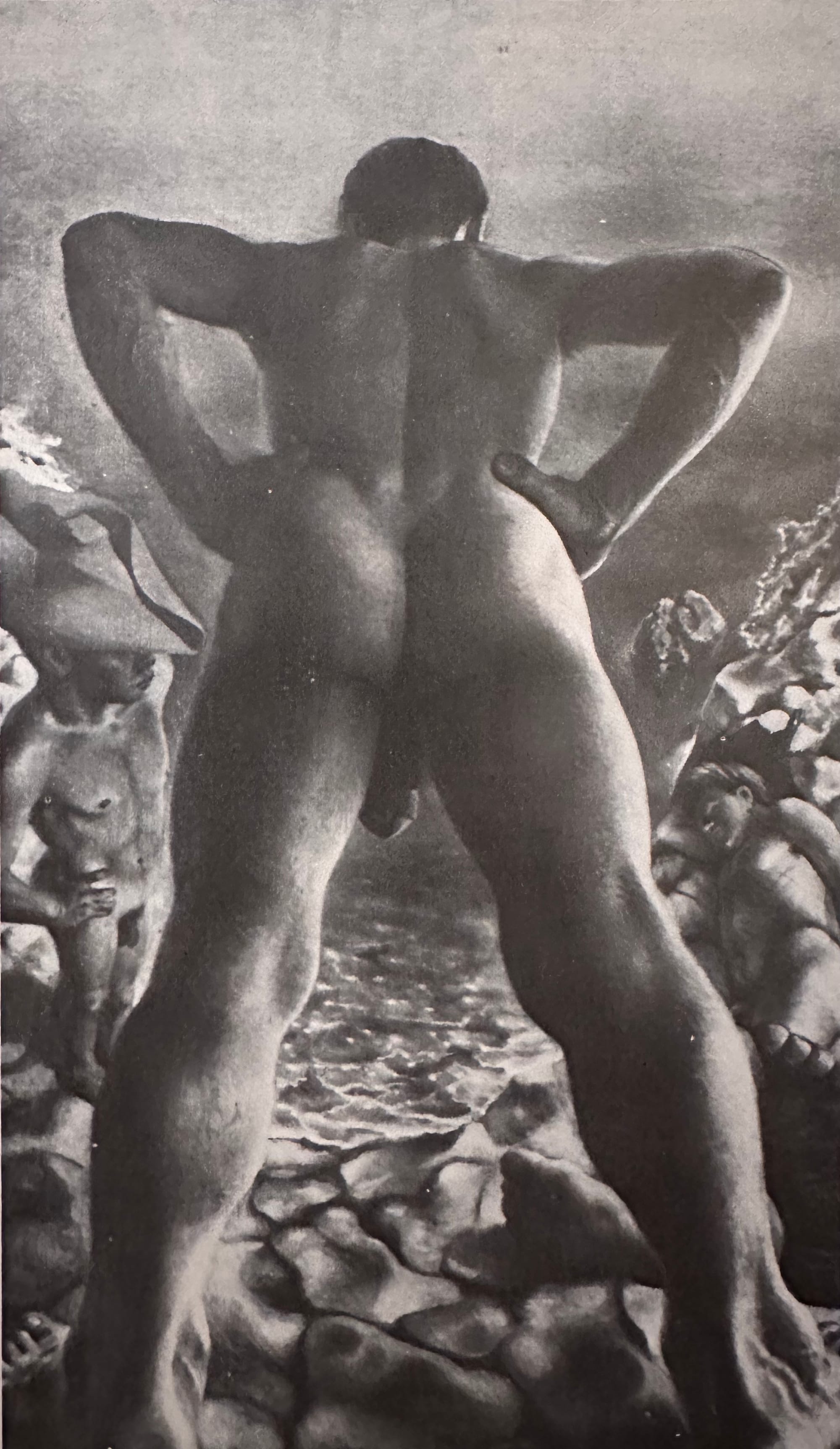

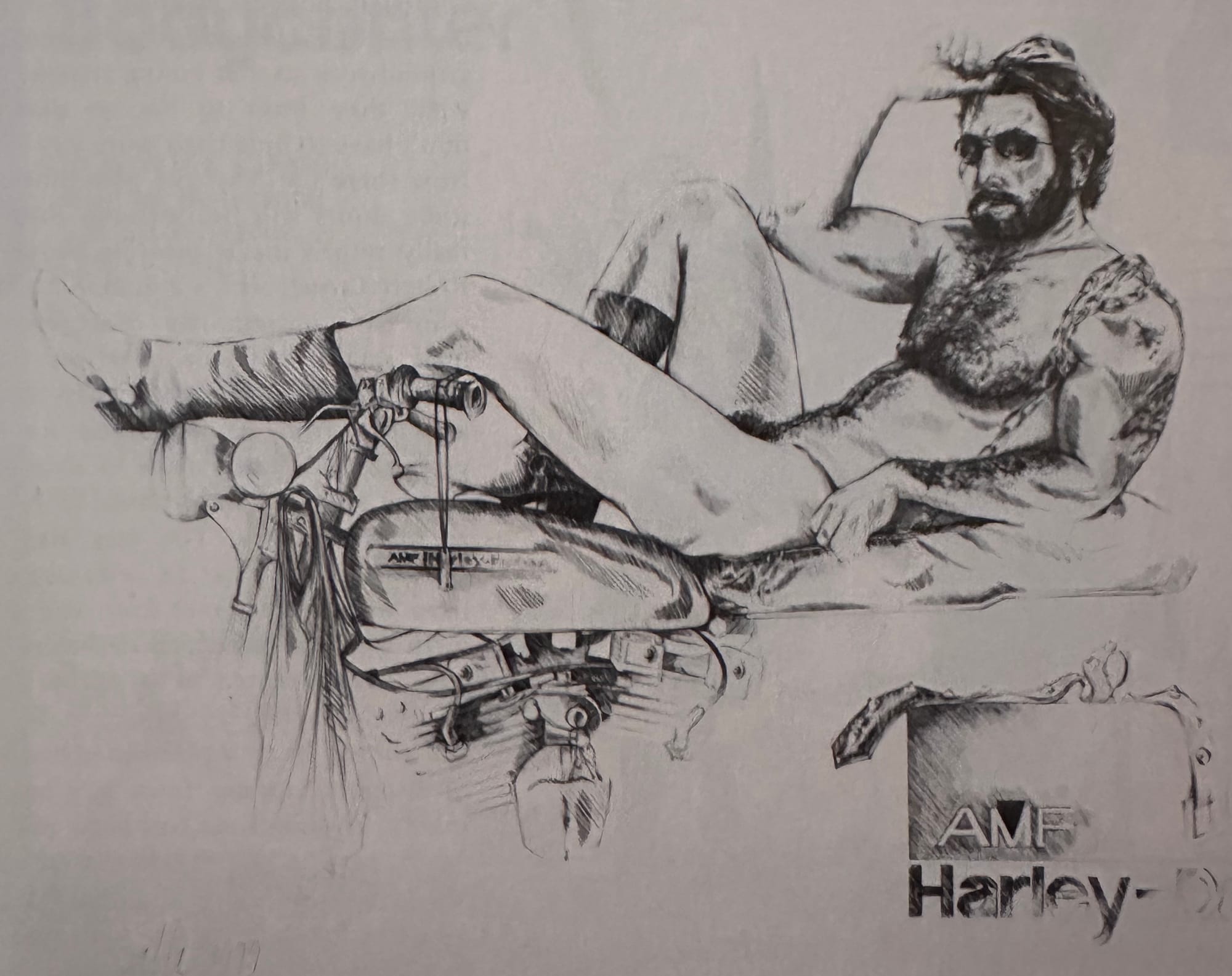

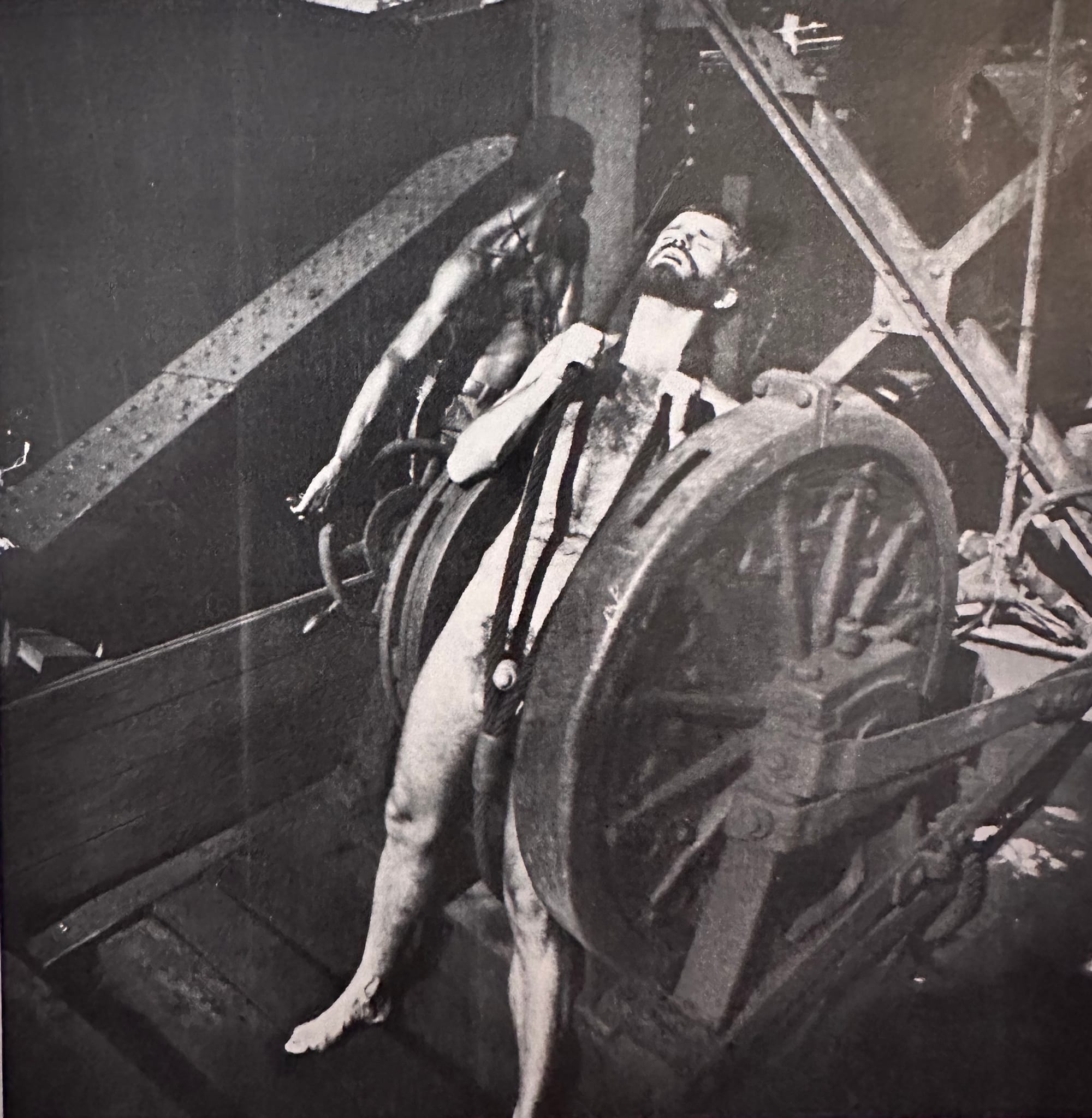

What has made acceptance difficult for some viewers is also the source of the most consistently negative criticism your shows have received—the supposed presence of violence and brutality in certain male images, and particularly in the photos of Mapplethorpe and Tress. There is also the related issue of pornography. You have said that a good deal of the visual education of today’s artists was formed by pornography, and it is significant that your first exhibition included works by Tom of Finland and Rip Colt. I know you’re planning a Tom of Finland show in February. In fact, the exhibition of Robert Mapplethorpe’s early work that was in the gallery in November bore out the truth of your remark because it showed in several pieces his fascination with images from skin magazines. I think that many artists working with the male image today find themselves between two traditions—the classic, going back to Greece and strongly modified by the Renaissance, and the pornographic. Somewhere in between these two extreme poles we are witnessing the beginnings of a new tradition that hasn’t been defined yet, and that’s what makes this such an exciting time.

Exactly. It’s all a question of what you had to look at, what you had to identify with. If you were an artist who wanted to work with the male nude, you had, in addition to the great masters, Thomas Eakins or Paul Cadmus to look at. Dali also did a few male nudes, and Picasso did some beautiful male nude etchings. Some artists looked at these works, some at pornography, and others at both.

I don’t mean to suggest that the violence comes solely from pornography. In this respect even the two traditions I mentioned are not so far apart. After all, the history of art is filled with nude battle scenes and wrestling bouts, crucified Christs and brutalized naked saints, and today’s skin magazines never tire of doing variations on the image of St. Sebastian, who early became an archetypal homoerotic figure.

Yes, with the exception of most Greek works which aren’t particularly violent, the whole history of the male image in art is very violent. There’s a point somewhere in time when the only way a man can deal with another man is to totally mutilate his body in some form or another. Today, an artist who wants to deal with the nude and have success has to work with the female nude, because how can a man deal with another man romantically? It’s not acceptable. Women artists, on the other hand, can be romantic.

That leads to another criticism directed at gay artists—that their works are impersonal, overly concerned with surface, and lacking in psychological depth. It is interesting that this kind of criticism, which has been made particularly of the photographs of Tress and Mapplethorpe, has come primarily from gay men writing in gay publications. Although they do not say it directly, what comes through is a sense of frustration over the fact that gay artists have failed to show what they should have understood better than others—the deeply human bonds that can be formed between two men. But I think that these critics themselves sometimes fail to recognize to what extent gay artists are still men; that is, still shaped by a masculine vision of things. They should also recognize that homosexuality emphasizes things male, including qualities that have been traditionally considered masculine, such as force, strength, and even a certain brutality. But these are precisely the realities that are often rejected. Shelly Rice, writing in Soho Weekly News about the Tress show (which she generally liked), said that the violent images hardly affirmed the new man she fantasizes about meeting in the future. And Lester Burg, commenting on the same show in Gaysweek, said that he hoped someday to see images that didn’t include so much brutality. Do you see yourself in any way involved in fostering such changes in the male image?

I would like to think so, not necessarily because it is strictly my point of view, but because it is a point of view that is very valid. But the change won’t come until artists like Sable, Tress, and Mapplethorpe first pave the road, and they are beginning to do that now.

That’s important, because you’re saying that the evolution can’t be short-circuited.

Absolutely. If these artists were not attracting attention by exhibiting their work, then the next generation of artists would not have the freedom to deal with the male image in a way which they would like.

I think we should make the point that these artists are not using violence as a way of getting attention or selling their work.

Mapplethorpe has been accused of that, and it’s not true. I know Robert, Arthur, and Kas well. They are very serious about what they are doing, and they are also concerned about what will be done fifteen years from now.

For me, the violence in Mapplethorpe’s photographs is never facile and is always strictly controlled in a fashion one has to call classic. And if some of his works are related to pornography, they also recall certain medieval and Renaissance images of religious torment and ecstasy. In Tress, the violence is less in acts than in gestures that are part of a larger fantasy or dream. In other words, here again the violence is partly neutralized and absorbed by other considerations.

One of the differences between Tress and Mapplethorpe is that Tress is basically exploring his own fantasies and projecting them on another situation, on another person, whereas Mapplethorpe is documenting a fantasy reality that is coming from the person he is photographing.

And both are also providing us with documents of a particular moment in gay history. We can’t expect to have a gay culture set up in a certain way and the artists to be radically separated from it. These men are going to reflect at least part of the gay world as it is.

In general, the response to Mapplethorpe and Tress has been very positive. But some people don’t go past the surface elements. They are repulsed by a scene of sadomasochism or by the simple fact that there’s male nudity.

We were talking before about reading signs, and these examples show how distorted things can become if one doesn’t read all the signs or sees only the most blatant ones. It’s a little like going to Christopher Street and seeing a lot of men dressed in leather and boots, and seeing only that, or not seeing the poetry of it, or not seeing beyond it. It’s the same kind of problem that causes some people to see only facile pornography in images which are really presenting a far more complex eroticism. I also think that Mapplethorpe and Tress have produced greater controversy because they work in photography. As Jackie Livingston remarked after her difficulties at Cornell, painting a nude is one thing, photographing one is something else, because the photo is seen as more real. In all this I’m not trying to make excuses for Mapplethorpe and Tress, whose works I like very much, even though I think some of the criticism directed against them is justified. Mapplethorpe on occasion is overly slick, and Tress does sometimes lack subtlety. But much of the criticism has been unjustified, and what interests me are the reasons for certain types of reactions to all forms of male-image art.

Look at it this way. There are those who are aware visually, and those who are not. When you get to people who are aware visually, they’re not that aware of what the figure is about any more because it got lost somewhere. Then when you narrow it down even closer to the male figure, you’ve got a lot of those identifiable objects that you see one way and someone else sees another way, and you get into a lot of strange contradictions.

Well, contradictions can be revealing and even a lot of fun if we accept them and learn to play with them. I think artists realize today, whether they want the responsibility or not, that they are involved in redefining man, which means shaping a new image out of materials and models that are necessarily contradictory and that carry a heavy political and social weight. It certainly isn’t easy, especially for a gay artist who, in addition to the general taboo against male nudes, has to fight the more specific problem of homophobia and the pervasive ignorance about gay life. Historically, gays have had a marvelous talent for recycling and reshaping cultural elements of all kinds, and I think one has to admire and enjoy Mapplethorpe’s success in fusing together different artistic traditions, or Tress’s ability to transform signs, or even Sable’s way of undercutting the macho mystique with humor. If we don’t catch this play, we’re missing a lot.

That’s true, it’s very true.

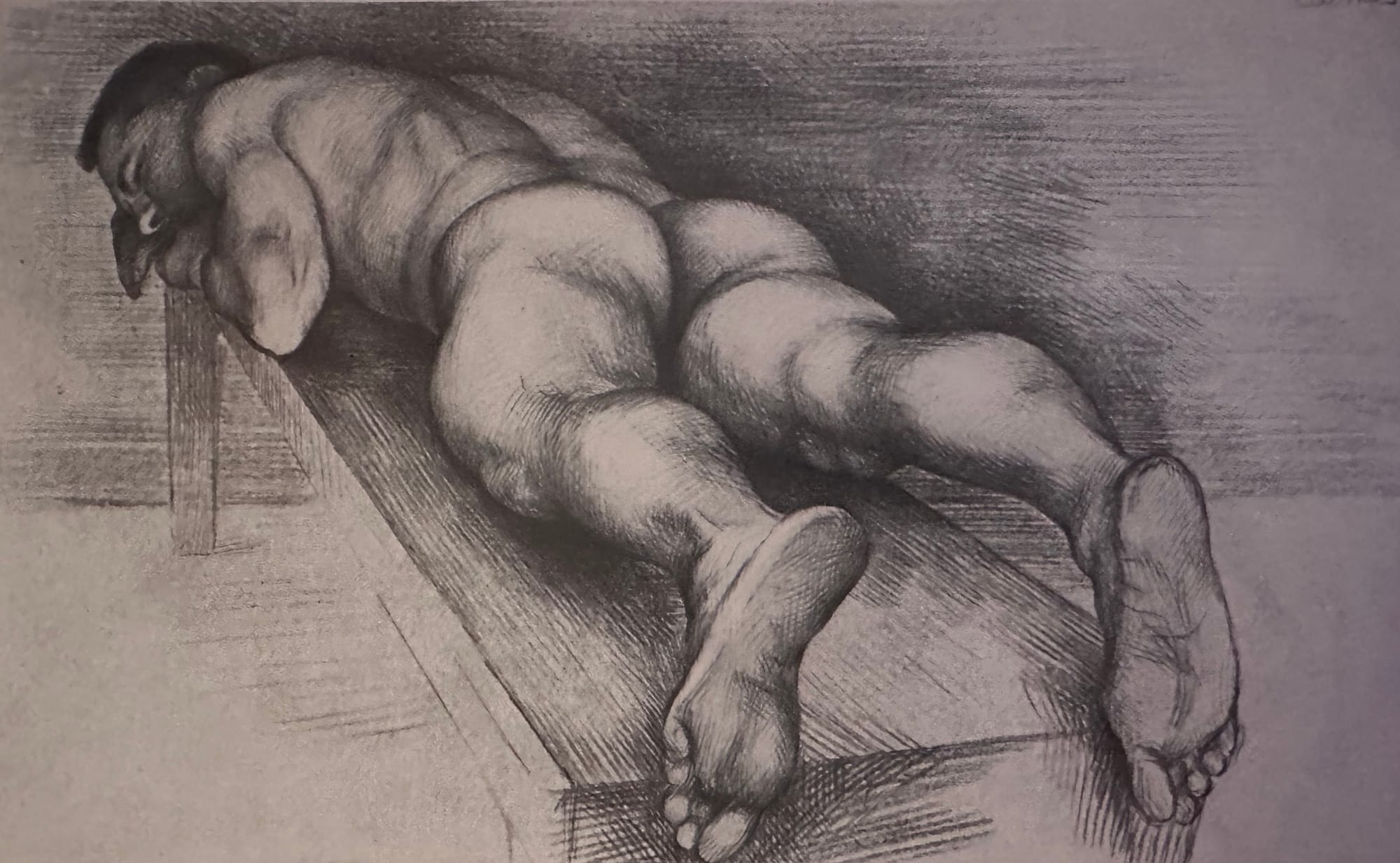

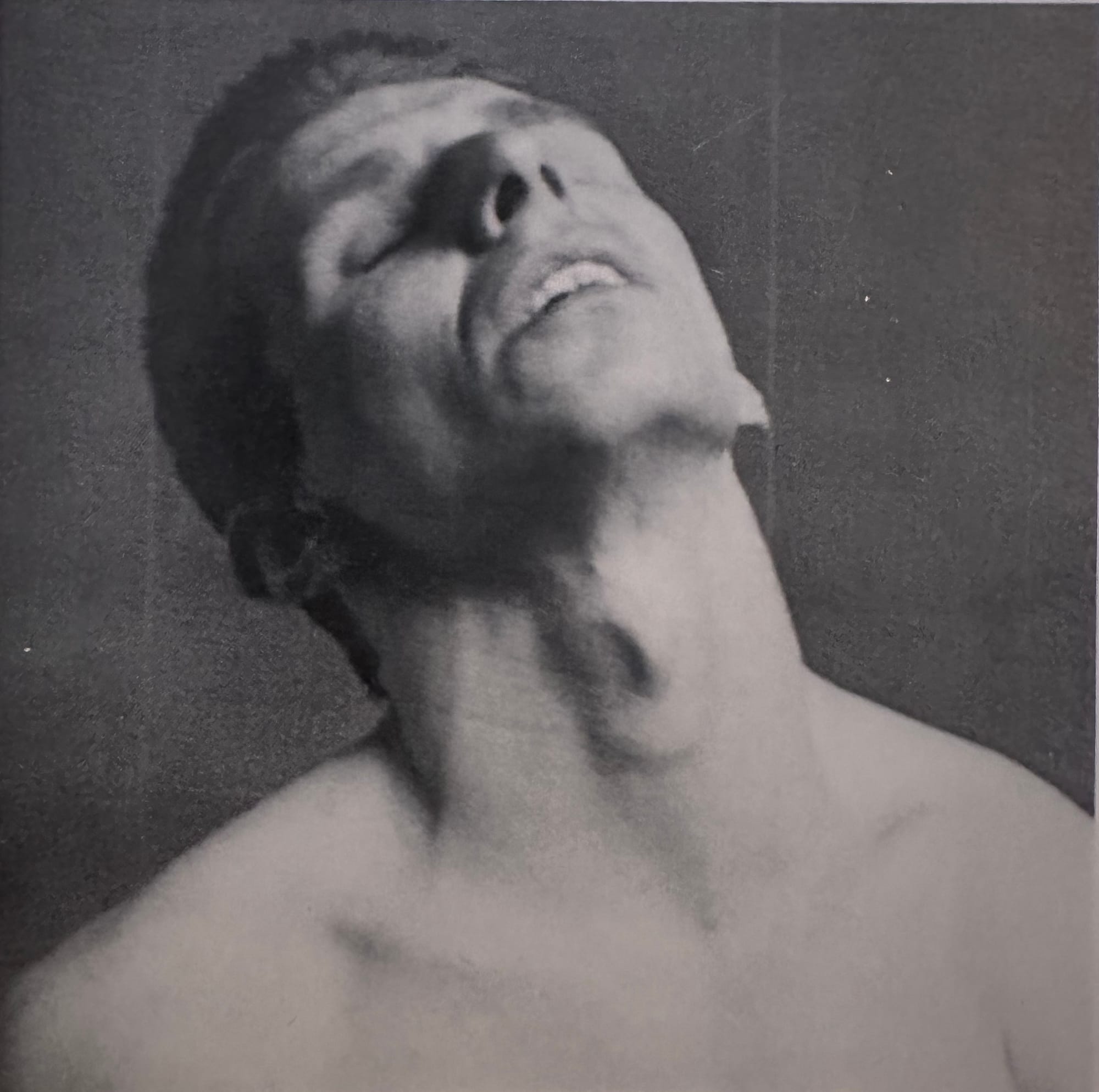

Up to this point, we’ve been talking about male artists, and historically most of the images of men have been done by men, straight or gay. It seems now, however, that more and more women are becoming interested in the male image, particularly in photography. What has struck me in their works is their ability to see men as children; that is, to see the child in man. Gay artists may show playfulness, but women show man’s vulnerability and his need for love and warmth. Jackie Livingston recently remarked that men can be nourishing, especially to each other, that they can be open and comfortable about their bodies, and that they can be vulnerable. Men do not usually see themselves or show themselves in these ways, and it’s here that male artists have much to learn from women.

I hope that the women’s exhibition next season is going to have that influence. It will include photography, drawing, and painting by artists like Alice Neel, Audrey Flack, Patti Smith, Nancy Grossman, Jacqueline Livingston, and many others. There is no question that a woman’s point of view is very different from a man’s.

You said before that women artists tend to be more romantic in their treatment of the male image.

Yes. The one word that you use that is so obvious to me in women’s portrayal of men is vulnerability, allowing a sensitivity to come through that men never, or rarely, allow to come through, even gay artists. They have a tendency to make the male nude a very strong, macho, hard image. Again, it has to do with the way men have learned to deal with men romantically.

Most of the romantic images done by gay men have struck me as forced and inauthentic, or at least less authentic than the harder images. I think that Tress’s weakest pieces, for example, have been his romantic ones. Perhaps women will be able to renew the romantic vocabulary, but many men still see it as used and rather old-fashioned. What is more telling is the fact that gay artists usually do not show men as being comfortable with their bodies. In much of their work, they seem more interested in the uses of the body than in its being at ease with the world or with itself.

There’s no question about the control of the sexuality factor in male-image art coming from men. Women treat sexuality also, of course, but they do it more as part of a one-to-one individualistic approach to a person, as opposed to men, who treat it almost as a mass product.

That may arise in part from the promiscuity in some areas of gay life.

I think that has an enormous amount to do with the male-image art of gay men.

We know that sexual tastes can have a strong influence on aesthetic tastes, particularly in the area of figurative art. It is not surprising, therefore, that the vast majority of works you have shown have presented men who are young, beautiful, and well proportioned. Although the beautiful body has a long tradition in art, can you be criticized for your choices or for not showing much of the grotesque, for example, which also has a well-established tradition?

There is an opening for criticism on that level, because I remember Ben Lifson in the Village Voice saying that Mapplethorpe’s people were all fashionable and glamorous. But I don’t think of his work in that way. An artist working with the visual image of a man is going to treat something that satisfies him or just the opposite. Most of the men hanging on my walls are going to be attractive, well proportioned, etc. However, that’s not why I’ve chosen them. I’ve chosen these works because they are the best being produced by artists who are the best ones dealing with the male image.

Weren’t you also criticized in the beginning for showing only works by men?

When I first had the Man to Man exhibition, I had a head-on confrontation with a woman from a feminist magazine, who asked me very angrily why there were no works by women in the gallery. She said she was going to expose the whole thing and see that we were attacked. I explained that I was not making a stand against women or feminist groups, but if anything I was making a stand for women, because it would lead to a freedom for women to deal with the male nude as they would like. Later I wrote a letter to the magazine and asked that if they were going to send someone to cover the exhibition, that it be someone who knew something about the history of art before jumping on me for political reasons. I did get a response with an apology, and the story was never written.

Then you realize that, whether you like it or not, you and the male image are involved in politics, gay and straight.

It is a very strong political issue within the art community. I’ve lost friends over this gallery. I know one particular gallery director, whom I respect very much, who resents the fact that I’m doing this, because she thinks that it’s very dangerous, particularly for gay men showing with me, because they’re going to be labeled and branded in some galleries in this city. On the other hand, I’ve alienated some gay men who believe I’m exploiting male-nude art, or who believe that there is no taboo against this art in other galleries.

The charge of exploitation was inevitable. It comes whenever someone thinks that commercial considerations are overriding aesthetic ones—for example, when the sexual aspects seem overly emphasized or when the work is inferior in quality or judged to be inferior.

As I said before, I’m presenting the best male-image art that is accessible to me right now. I’m also keeping a decent ratio between what is established and the non-established. If it’s successful, then artists are going to be able to survive by means of their art, and it’s going to be a reasonable process dealing with other galleries.

What is very encouraging is that your shows are educating not only the public but also other artists. Have you had any reaction from younger artists? Has the existence of the gallery brought some out of the closet?

Oh listen, not just younger artists, older ones as well. Hopefully, we’re laying the groundwork so that young artists can do what they want to do, so that they don’t have to hide their work any longer. Now there’s at least the possibility that some doors will be opening. But what really moves me is meeting people like Robert Crowl, who’s a man in his fifties who has continuously dealt with the male image, but in a relatively private fashion. Galleries had repeatedly discouraged him from painting male nudes. A year ago I offered him an exhibition, and he has started to paint. The works are extraordinary. The man has a life about him now that he certainly didn’t have when I first met him. It’s the rebirth of a man who’s finally doing what he’s always wanted to do all his life. So yes, we’re having an influence. This season there’s been a phenomenal amount of support coming from gay men primarily. It makes me feel very good. My job is now to get together top quality exhibitions so that all those critics, reviewers, and supporters can stand behind me validly. I’m in a particularly vulnerable position right now because a lot of people are watching the gallery very closely. ❡