This article appeared in the May 1981 issue of Christopher Street, on pages 59-61.

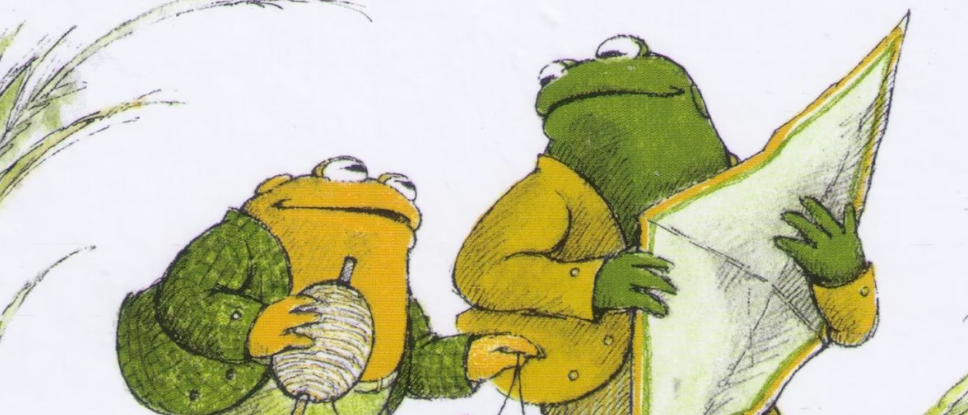

Frog and Toad Are Friends

by Arnold Lobel

Harper and Row, 1970

84 pages, $7.95

Frog and Toad Together

by Arnold Lobel

Harper and Row, 1972

84 pages, $7.95 hardbound

$1.95 paperbound

Frog and Toad All Year

by Arnold Lobel

Harper and Row, 1976

84 pages, $7.95

Days with Frog and Toad

by Arnold Lobel

Harper and Row, 1979

84 pages, $7.95

IT IS OFTEN NOTED that literature contains few full-blooded portrayals of real friendship. What is even stranger is the rarity of such portrayals in children’s books. After all, books about adults are usually about adultery, a subject children’s books tend to avoid. You might expect the empty space to be filled by the subject of friendship, but no, the great majority of children’s books are about lone individuals dealing with the obstacles of the world. The obstacles can come in the guise of a fire-breathing dragon, a logic-chopping caterpillar, an anarchistic cat in a beat-up top hat, Farmer McGregor, a stony stepmother, or the protagonist’s own stupidity. Occasionally the protagonist is given company, maybe a sibling or a pet, but the company is there only to provide a spectator or an additional obstacle. Even when the stories are closer to home and take place in the real world of backyards and classrooms, friends only take the form of a gang, a heartless, polyfaced Hindu god that usually goes by a name like Samandjimmyandmaneandanna. The one-on-one friendship that is the source of so many pleasures and aggravations in childhood is bizarrely absent in children’s books. It was this absence that must have been noticed ten years ago when writer and illustrator Arthur Lobel began a series of stories for beginning readers about the adventures of two friends. To the limited company of great fictional friendships—Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, Huck and Jim, Bouvard and Pecuchet, Jules and Jim—Lobel added the names of Frog and Toad.

Frog and Toad are, as their names suggest, a frog and a toad. Frog is green, tall, usually dressed in striped trousers and a brown sports coat without a collar. Toad is brown, shorter, and wears a green plaid jacket with green trousers. Neither wears shoes. Their world is an odd mix of the anthropomorphic and the natural, the child-like and the adult. They live in tiny Tudor cottages that are surrounded by immense stalks of grass and flowers as big as suns. They are financially independent bachelors who are given to drinking copious amounts of tea, and yet have the emotions of two very perceptive six year olds. It is the world of The Wind in the Willows, only scaled down for a younger reader, and if there is a precedent for Lobel’s work, here it is in Kenneth Grahame’s chapters about the friendship of Mole and Water Rat.

In themselves, the Frog and Toad stories are not cause for wonder. They are cleanly written, well-illustrated, occasionally achieving a snap that even an adult can enjoy, but with nothing that really lifts them above the better tradition of imaginative beginner books that includes the work of Maurice Sendak, some Dr. Seuss, James Marshall, and other books by Lobel himself. But in the context of children’s literature, the focus of the Frog and Toad stories is new and even quietly exciting. For here the source of interest is not the friends’ adventures, most of which are trivial even by the standards of the most undemanding child, but the give and take of their friendship. Not even Kenneth Grahame makes the reader so conscious of the work involved in friendship, or of the pleasures that make that work worth the effort.

Most of that work is the result of the different natures of the two friends. Toad is somewhat neurotic. He worries tremendously, loiters in bed (five of the twenty stories begin with Toad, like Oblomov, ensconced in bedclothes), and tends to obsessive-compulsive behavior: he must do this, he must do that (Wake Up, Get dressed, Eat breakfast, Visit Frog—a very simple lifestyle, even for an animal). Frog, on the other hand, is sanely healthy. He likes sports, gardening, and telling stories. He is occasionally imperious. If Toad was in the movies, Toad would be played by Woody Allen, Frog by Gerard Depardieu. It is an uneven relationship, with Toad often playing the younger brother to Frog and there is the feeling that he needs Frog more than Frog needs him. But the deck isn’t stacked so that either the reader or Frog feel smug toward Toad. On more than one occasion, Frog’s common sense comes out second best to Toad’s neurotic instincts.

Lobel plays down the didactic intent by filling out the books with episodes that do not bring friendship to trial: Frog and Toad eat cookies, Frog and Toad fly a kite, or go sledding or rake leaves. They do things together, but they do them differently, and their friendship serves only as a backdrop. But it is when Lobel is at his most didactic and brings friendship to the center, usually in only one story per book, that the tales seem to catch fire.

Such a story is “The Dream” from Frog and Toad Together, in which Toad dreams that he is performing in an enormous theater with only Frog for an audience. “PRESENTING THE GREATEST TOAD IN ALL THE WORLD!” announces a distant voice, and Toad proudly plays the piano, walks a tightrope, and dances. Each act is applauded by Frog, who confesses that he can do none of those things. And as he applauds, Frog becomes smaller and smaller and smaller, until he disappears. Toad sees what he’s done, breaks out of his narcissism, cries out for Frog, and begins to spin in the empty darkness. Suddenly, Toad wakes up and finds Frog standing beside his bed. Toad is overjoyed to find his friend back to his usual size, once again the same, big contented lug, standing in the bedroom with one hand in a pocket.

“Frog,” he said, “I am so glad you came over.” “I always do,” said Frog.

And the two go outside and spend the day playing together. The story is amazing not only because it opens a can of worms—the dream is weighted with Toad’s resentment of always being the inferior—but because it promptly throws the worms away. Questions of who is better or smarter or stronger only threaten a friendship and have nothing to do with its pleasures. The pleasures are obvious in Toad’s joy and Frog’s quietly loyal, “I always do.” No psychoanalyst ever discarded the worms more deftly.

In the same vein is “Alone,” the last story in Days with Frog and Toad. Toad finds a note on Frog’s door saying that he has gone off to be alone. Toad is disturbed by the note, hunts for Frog, and finally sees him on a rock in the middle of the river. Deciding that his friend needs to be cheered up, Toad fixes a lunch of sandwiches and iced tea and gets a turtle to take him out to the rock. The turtle, one of those obnoxious creatures who agrees with everything you say, echoes Toad’s fears that maybe Frog wants to be alone, and even that Frog doesn’t want to be Toad’s friend anymore. Stirred into a fit of anxiety, Toad falls off the turtle and into the river. Frog pulls Toad and the lunch basket onto the rock and consoles Toad for the ruined lunch that was meant to make him happy.

“But Toad,” said Frog. “I am happy. I am very happy. This morning When I woke up I felt good because the sun was shining. I felt good because I was a frog.”

And, of course, he felt good because he had Toad for a friend.

“Now,” said Frog, “I will be glad not to be alone. Let’s eat lunch.” Frog and Toad stayed on the island all afternoon. They ate wet sandwiches without iced tea. They were two close friends sitting alone together.

What I would give to have written that last sentence.

By now, you are probably wondering, both because of this review and the nature of the magazine you are reading, if Frog and Toad might just possibly be, well, gay. True, they do not sleep together or even share the same house, but the intensity of their attentions and worries certainly point in a homosexual direction. I do not want to entertain that possibility. The scope of the stories seems so much broader and, although Frog and Toad are more consistently loyal and kind than the children I remember or know, the fervor of their relationship rings true for all childhood friendships. Such friendships are our first opportunity to connect with someone to whom we are not bound by authority or physical need. They don’t always make up in intensity for what they lack in duration, but perhaps they serve as half-forgotten models for our relationships with people when we grow older, whether as friends, spouses, or lovers.

Lobel chose to take these original contacts seriously. And he chose to make those contacting creatures male. Simply by changing pronouns, he could have made his friends female, or one female and the other male. Society expects its females to be sharply conscious of each move in the intricate business of their friendships, but expects its males, even as children, to be above such attention to emotional detail. By making both of his friends members of the “strong” gender, Lobel goes against convention. He never draws attention to this revolt. Lobel presents his amphibians’ attention to details as something natural and unbounded by gender, which it is. Not only do Frog and Toad live in a fulfilled dream of loyalty and kindness, they live in a world that approaches a true sexual democracy. ❡