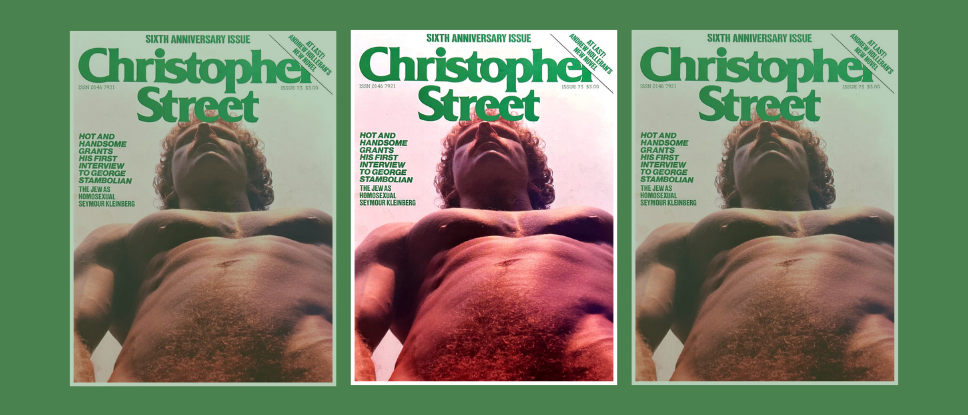

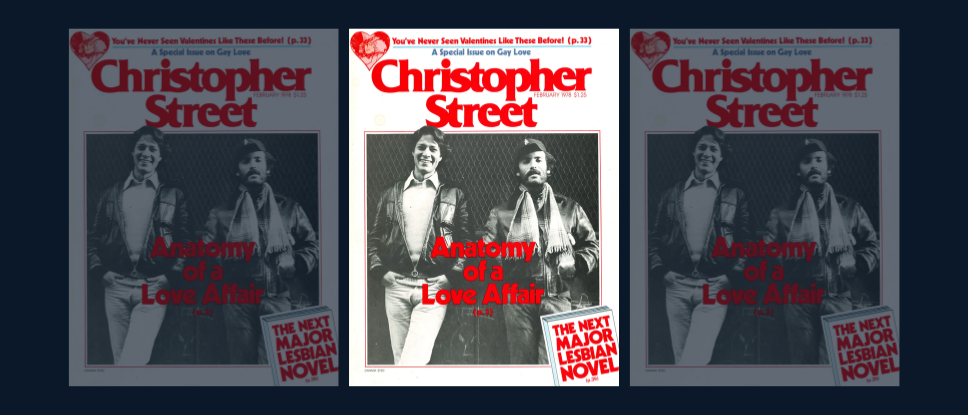

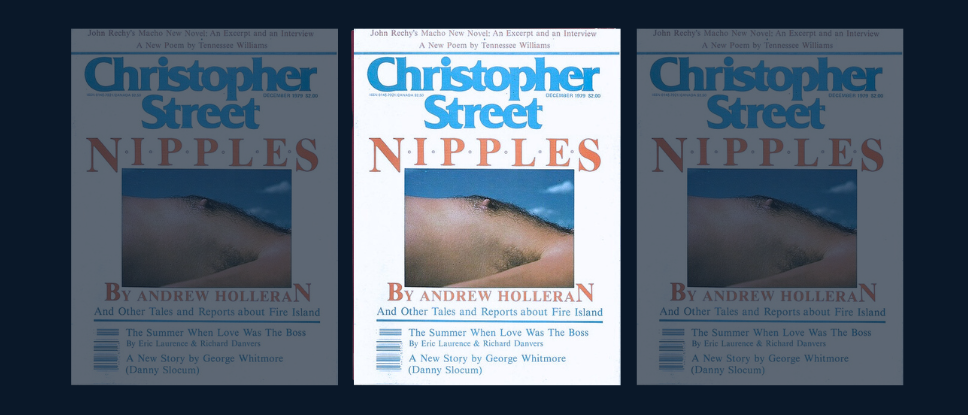

This story appeared in the December 1979 issue of Christopher Street.

ONE HAS ALWAYS had nipples but one became aware of them only last summer, on Fire Island, on a quiet midweek night devoid of the suppressed hysteria which defines the dinner table on Saturday night, when everyone is going out at two to dance at the Ice Palace and wondering which drug to take. No, on a Wednesday evening it is not at all imperative that you go out; the prospect is something to be considered between yawns, over coffee, around midnight, when the dog at your feet looks up as the conversation pauses and everyone stares at him. On a Wednesday evening in midsummer with the fog drifting over the dunes and a profound silence emanating from the houses on either side of ours, which until this day have played Evita so loudly the fact that our own tape deck is broken is irrelevant, shirtless in the light of the candles on the table and amid the intimacy that five-for-dinner allows, the conversation becomes almost grave. We talk of lovers, and if people really want them or only think they do; we talk of books we’ve read; someone even reads our palms and then, rather than retire, for it is still early, we talk of nipples.

It has been a strange mélange of the concrete and the purely abstract all evening, in fact. In our room downstairs on this quiet night, while we wait for our chicken to bake, a housemate says to me, “I’ve had a wonderful breakthrough in therapy this week.”

“Oh? What?” I ask, leaning forward with the sense that something profoundly human—something elicited by the silence, the fog, the wash of the surf—is about to be revealed.

“I can suck cock now without being nauseated,” he says.

“Oh,” I say, sitting back in slight confusion. “I didn’t know it used to nauseate you.”

“Couldn’t stand it,” he says. “But now I’m getting better. I did it last night, for example. No problem.”

“Well—” I say. The word “congratulations” hovers in the air, but it hardly seems appropriate; I allow “That’s wonderful” to sink to the floor while the dog looks up at us.

The sense of communion after dinner is even stronger: the candlelit faces, the wash of the surf, the dog indifferently dozing, the burning cigarettes in hands suspended in midair before a magic circle of bronzed chests. The words which emerge are these: “Have you been noticing nipples?”

“Yes!” someone says instantly, as if he has been wondering about the same thing himself. “Nipples are in vogue this summer,” he says emphatically.

“Really!”

We sit forward at the announcement of a trend.

“Absolutely. I’ve been noticing them for some time now. They’re getting much larger, more cultivated, more distended, more prominent. I’ve noticed nipples becoming more . . . distinct, on several of my friends.” Everyone is suddenly abashed, their nipples quite clearly the objects of some attention. “Have you seen—?” and here he names several people whose nipples, we have all noticed, protrude from their chests like heads of yarn. “Do you enjoy your nipples?” someone asks.

“I haven’t particularly, till recently,” he replies. “But I think it’s something one learns; it’s an erogenous zone one develops.”

“Yes,” agrees another.

“I love nipples on other people,” he adds.

“Oh, quite,” the man who introduced the topic says. “I could dangle them for hours. I wanted to go into the dunes yesterday and just munch on nipples.”

“Women’s nipples change color after they’ve had a child,” I offer. “They become dark.” But this is irrelevant; it elicits nothing more than a few glazed nods. “I find,” I begin again, hoping to be more on point, “that in the baths nowadays, when people meet in a hallway and stop and negotiate erotic matters, they often play with one another’s nipples first. Before, they simply grabbed the crotch. Now they stand there dialing each other’s nipples like men trying to tune in a radio.”

“I had a boyfriend once who went crazy,” a friend says in a slightly awed voice. “One touch and he was yours.”

“Some people feel nothing at all,” I add.

“Then they should go to San Francisco,” he says, “where you can take a course on getting in touch with your anus. I’m sure they have something for the nipples, unless it’s taken for granted, as it probably is there, that you’re in touch with your nipples.”

“In San Francisco, they paint their nipples,” someone else says. “In concentric circles. On Castro Street. Which is not surprising, I guess,” he finishes.

“What do you think of pierced nipples?” someone asks.

“Ghastly,” comes the answer. We are a traditional group.

“Are nipples an index of penis size?” someone asks.

“Not at all,” cries his roommate, and everyone, seated shirtless at the table, begins wondering what his nipples tell of himself. “There is no connection. A friend of mine who used to search for that El Dorado, the test for penis size, tried and had to give up using noses, feet, hands, earlobes—”

“Earlobes!” someone says.

“Earlobes,” he replies. “My friend thought thick earlobes a foolproof sign. Well, it isn’t so,” he says indignantly.

“Thank God,” someone sighs. “Imagine going to the Meat Rack tonight to feel earlobes.”

“There is no correlation,” the man continues. “It’s as hopeless as looking for the Northwest Passage!”

“So nipples do not indicate penis size,” says another, who, due to his experiences with hospital budget meetings, is accustomed to summing things up.

“No, they do not,” says the man.

“Well, what good are they, then?” asks someone brightly.

“Nipples?” says my housemate, in an elevated tone. “Nipples are the windows of the soul.”

❡

At the end of July, one of my housemates hears of an opening for a houseboy in a place on the beach which has always been considered one of the most beautiful houses in the Pines, a house whose simple and elegant architecture exemplifies what is best here, an emblem of that unspoken pride gay men have in their taste and ability to produce beautiful designs. The Pines has its share of architectural junk, to be sure, flung up in the building boom which has filled nearly every empty lot in the community these past few years, but if there is one, when, if you came to the Island, the air was contrapuntal with the sound of hammers. But the house in which my friend becomes houseboy is one of the very finest, and one evening we all decide to go over and sit with him on the deck to enjoy its beauty. It is a house purchased by men from a southern city, but to us it will always be a house which belongs to the previous owner, a New Yorker whose end was a scene from Looking for Mr. Goodbar. His ashes are purportedly near the deck.

Solitary runners float past the dunes, their heads bobbing up and down. The sun begins to set. We can see no other houses, only the pristine seascape, only the sloping lines of dunes, the wild roses, the wild grass and the milky blue sky which has suddenly become precisely the same shade as the ocean. We were never invited to this house by the deceased owner; he had his own circle of friends, now middle-aged, who, in the days when we first came to Fire Island, could be seen playing volleyball at a net near the house. The net still stands. The players have disappeared, although not as luridly as their former patron; they have simply vanished from the scene.

We sit sipping our wine and watching the play of light on the weathered cedar curves of the house, the pots of geraniums and petunias on the steps, and feel no remorse. Fire Island is a curiously public community, and one may find oneself in its homes through circumstances far less coincidental than these. It does not bother my friend that he has suddenly become a houseboy at thirty-three; we all have our summers at different stages in our lives. This, we discover with an odd absence of those considerations that define our lives on the mainland, is la vie en rose.

“You’re not afraid you’ll be bored?” I ask him. “I tried to live out here one summer and it drove me crazy. I thought I wanted a summer on the Island more than anything else in the world, and I was so glad the day I went back to Manhattan.”

“I’ll go back from time to time,” he says, “if I get crazy. But darling,” he says, putting down his drink and looking at me to share an ideal almost every one of us has had at some point in his youth, “I’ve always wanted to spend the summer out here, and who knows when I’ll have the chance again?”

It is the dream of everyone who has ever hated his job, or city, or the very limitations of life itself. As the dusk deepens before us, with its ascending moon, the opalescent waves, the runner floating past the dunes, it is hard not to conclude that if an earthly paradise exists, this is it.

❡

“One has to be rich and beautiful to go to Fire Island,” a friend writes me from Oregon. “Nonsense,” I reply. One has to be rich or beautiful, I am tempted to add; but this, if witty, would be untrue. The Pines is composed largely of people who are neither rich nor beautiful, although occasionally, as in the house next to ours, that alliance is achieved. The place belongs to an older man who simply likes to fill it with attractive youths, who spend their days naked around the pool and are endowed with the buttocks ordinarily given to dancers and to statues supporting lanterns on a bridge in Paris. The house is bursting with inflated beach toys, a pair of Afghans and countless plastic pendants. The youths turn Donna Summer up very loud, or Evita or KTU, and go out by the pool. It is like watching life on Fire Island as dreamed by a gay boy in Arkansas: Fire Island is lying by your pool listening to Donna Summer and drinking Piña Coladas. As opposed to the neighbors’ Fire Island, which consists of Mozart and walks at dusk. But the boys are all twenty-one, and what can the neighbors, who are ten years older, say? Nothing.

The neighbors marvel as they watch them come and go with their inflated rafts and their two Afghans, Marissa and Snowflake. The neighbors belong to the ordinary class composed of bankers, copy editors, ribbon clerks, attorneys, temporary typists, physicians, designers (apprentice and famous), novelists (aspiring and jaded), carpenters—people who return on Sundays to offices in New York and Washington; people to whom the summer is fraught with guilt (over spending what is easily enough for a month in Europe), worry (over whether or not you left the house unlocked, flirted unconsciously with a roommate’s lover, or ignored a friend in the city who should have been invited out), routine (whose turn is it to cook?), and a certain absence of privacy. It is even difficult to have sex on a weekend in the Pines, for the same reason that families living together in one room in Moscow find their personal lives limited. Then, too, the social fastidiousness of the Pines—the good taste, competition, and consuming gossip—produce a certain climate in which sex is the least possible of all things here. This is why Sunday nights at the baths are crowded with people just off the bus from Sayville who have endured a weekend of sexual stimulation so powerful it amounts to torture. This is not to say there aren’t houses to be found on Saturday afternoon where twelve naked men lounge around a swimming pool, and the bedrooms upstairs are filled with copulating couples. There are people who spend their entire weekends having nothing but sex. No, the Pines, like the Army—like life—cannot be the subject of a single descriptive sentence; it is what happens to you, just you, when you go out there.

❡

On one of those hot, sticky, white evenings in New York, when one would kill just to be in the Pines, just for the breeze, I overhear a conversation at my gymnasium between two people I first saw on the Island six years ago. They discuss the exorbitant rents, the increased crowds, the absence of their friends, and conclude that it would be nice to go out once this summer, but that next year they are definitely going to Europe. I wonder which has changed, the Island or they?

Is it an illusion that the Pines is more crowded, more frenetic, more watered-down? Is the Sandpiper really filled with heterosexual teenagers from the mainland on Saturday nights? Or have we simply become more finicky? One friend of mine cannot get over the fact that pizza is sold at the harbor. It’s true that the Pines is a long way from its rustic beginnings.

A friend calls up one Sunday from the Pines and says in a voice tinged with panic, “It’s mobbed out here, there are Puerto Ricans on the beach, they’re barbecuing a pig!”

A friend from San Francisco calls to ask, “How are the drugs out there this summer? I hear it’s very heavy.” I tell him I do not know. He then inquires, for a friend who is deciding when to return east, “Do you know if there are going to be any big parties before Labor Day?” I cannot answer that, either. He seems disappointed when I confess that lately I have been going to bed around midnight and have not been to a single fête; I feel guilty for not contributing to the Fire Island legend.

A housemate calls from the city one day midweek to say he is not coming out this weekend. “I have to be honest,” he says. “The weekends depress me.”

“Ah,” I say, with the coolness of a nurse who has seen all the symptoms before, “it always gets that way at the end of July. Take a break.” The summer, like a fever, has its doldrums. “Is anyone coming back to town?” he asks. “It’s not really all that important, but if someone is, I’d appreciate—”

“What?” I say. “I’ll be glad to bring it in, whatever you need.”

“My suntan pills,” he says sheepishly.

❡

A white tent appears on the beach the last Friday in July, and we watch from a nearby blanket as a group of men around the tent applaud individual speakers whose words are inaudible to us. It is a meeting for people interested in the Advocate Experience.

“Do you think it’s just that people are tired of the baths, the bars, the discos, the Pines?” someone on our blanket asks. “Do you think it’s just another way to meet people?”

Our friends are going to therapists, chanting, studying Gurdjieff, Zen, taking est, the Advocate Experience; one wonders if this is a movement of gay men in general or just of gay men my age, who turn quite naturally, in their mid-thirties, to matters which never concerned us during our more frivolous twenties. Even on the beach, which, alas, has come to stand for little more than the partying mob, this white tent reminds me of the tents in Saratoga a century ago, filled with people listening to speakers on the chautauqua circuit.

Someone on the blanket says, “So first they get their bodies together, then they get their personalities together. Then what? What is the point of a room filled with handsome, lean, muscular men with open, friendly, communicative personalities? Oh, give me a room filled with sullen beauties!” Then everyone sits up to watch the latest blond model from California, a perfect physical specimen of Man, walk by with X, after which we discuss who has the better ass.

❡

We end with this paradox: my house is filled with men who love the Island, but none is sure he will return next year. These men are perfect housemates. Veterans of summers past, they know how important it is to be considerate, to make and abide by certain fundamental rules—say, no guests without sponsor present. They have all spent horrendous summers in houses where no one was considerate and they vowed, Never again! Those were the summers that produced the hilarious stories. This summer we kept the place neat; each asked the others if anyone needed anything from the store or if anyone had any colors because we were doing a wash. We did not interrupt when people were reading. We wrote down telephone messages, we virtually competed with one another to do the dishes after dinner and (in keeping with the new mood of fiscal caution which seems to have swept over even the most spendthrift of New Yorkers) whoever was cooking on Saturday night went to the trouble of buying some of the food in the city, to keep the price of dinner down.

But if the outrages, the horror shows are gone, so are the glamour, the excitement, the thrill. We have learned how to shape the Island to our tastes; it can no longer pick us up and take us on a ride we never rode before. By the time you are mature enough to be considerate, you are too mature to be susceptible to social and sexual glamour. Tea Dance repels us; the Ice Palace seems too obligatory. What is the Island then? We recall an afternoon a friend who has not been here in two years arrives from the city and falls on his knees before the ocean, then does cartwheels up and down the beach. For this narrow line of dunes breasting the Atlantic is simply one of the most beautiful places on earth. He stands up to gush about the boy he saw on the boat coming over and we, who have allowed our experience of the place to sink beneath the weight of routine, have to smile and remember, Yes.

❡

The weekend our house closes, we are irrepressibly happy. The summer is over at last, Labor Day is behind us, the weather is indescribably gorgeous. “There are no words,” says a housemate, coming in from the moonlit, starry night.

At the Sandpiper that night, a friend turns to me and says, “This is Heaven!” And it’s a very good facsimile: the most handsome men we’ve ever seen are dancing around us.

We awaken the next day, eat blueberry pancakes and go down for our last swim. The ocean is the green of a tropical sea. We say hello to the people we pass on the boardwalk, as we did in the spring, and the summer seems like an enormous tumor which has been removed. The sheer number of people has been reduced to a civilized scale, and the Pines becomes the place that makes you wonder, against your better judgment, if you shouldn’t take a share again next summer.

For that is the illogical lure of it: as with perfect sex, an experience which may be rare in proportion to the time spent searching for it, we go back, nevertheless, for a few incomparable moments. One forgets being depressed by the crowds, the routine, the regimentation; the disco from the house next door and having to share one’s house with eight men and two dogs. Where else on earth is there anything like it? The gorgeous dusk, the constellations toward the end of summer, when you walked home slowly from the bar with X, stopped to kiss, lay down in the sand to seek out Orion, and kissed again in the perfect, windy silence. Love and nipples, and stars, and deer in the darkening dusk: around March we will be starved for the very things we are relieved to see coming to an end on Labor Day.

It is perfectly understandable that a man who has come to the Pines for seven summers should awaken one sunny Sunday in August and say to himself, “There’s nothing to do out here!” He may take an early train back to the city, go to his local delicatessen and find himself sitting happily at home with the paper, his rice pudding and his cat, while Tea Dance, which, seven years ago, so dazzled him when he came out of his room at the Botel that he decided on the spot to leave Washington and move to New York, is beginning in all its splendor.

But this is not to say that there is anything on earth quite like Fire Island, because there simply isn’t. It is simply to say that after many a summer dies the swan. Or at least that particular swan, whom you will now find bicycling in SoHo or sunning himself on the pier on weekends, while on the beach near that famous house, a new team is playing volleyball, a team of newcomers whose nipples one hardly notices. ❡