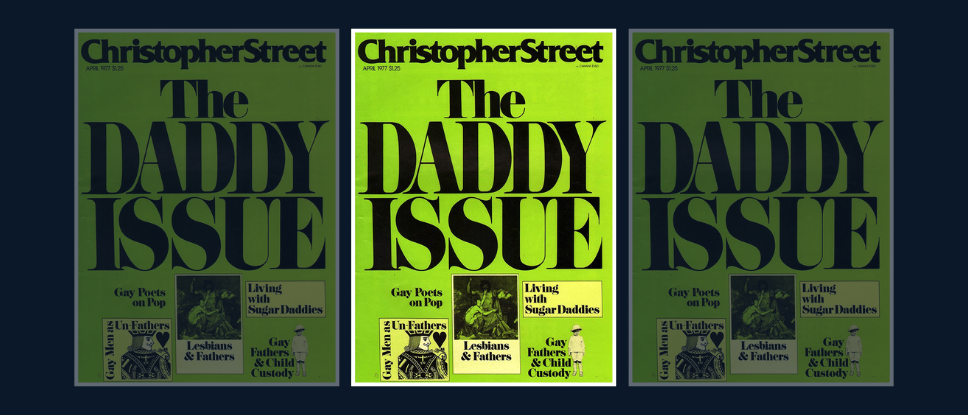

This article appeared in the April 1977 issue of Christopher Street, on pages 49-52.

A few years ago I read an article in the Village Voice wherein the heroine—by none of her own machinations—was transferred from the low life of SoHo lofts to the High Life of chauffeured limousines. Ah, wouldn’t it be… just swell. No matter how ambitious and independent a youngster may be, the thought of being delivered from the evils of poverty is always entertaining. We all know some poor devil who’s hit another’s jackpot and now participates in that rarefied life style, but don’t you ever wish it were you who found Mr. Rich? I used to.

The heroine in the story was lucky; she lived in SoHo and SoHo imbued her with all the colorful connotations of that area. SoHo-ites are a precocious, innovative, thought-provoking, charming, arrogant, or whatever it is that suits the wealthy. Me? I live on the impoverished West Side which frustrates my efforts at assumption into financial heaven. The upper, upper is nicer and a little safer than Harlem, but so lacking in distinction that it doesn’t even have what Harlem has: a name.

Though where you live can aid seekers of animate playthings in discovering your desirability and your poverty, there is another quality instrumental in snagging sugardaddies (what an awful term): exquisitely interesting, preferably good, looks. This I do not possess. My looks are about as unmemorable as the upper, upper West Side. Yet somehow I seem to have snagged more than my share of “benefactors” (yes, benefactor conjures up that delicately evasive smile so often the bond between the wealthy have-nots and the poor haves). In each situation I have had to face certain delicate questions which are considered so distasteful one dare not mention them in polite company—delicate questions I usually didn’t choose to answer.

Maintaining an ethical standard is difficult for me. Continuously vacillating, my standards or beliefs tend to become a bit confused. I attempt diligently to drown the confusion of my thoughts in miasmic agreement. It never works but my free-form logic keeps me amused and on my toes.

First of all, sugar daddies—pardon me, benefactors—aren’t necessarily extremely wealthy: it’s just that they all manage to make life easier and more enjoyable by helping financially. One gave me innumerable (daily) voice lessons, took me to dinners and shows, and used his influence to get me started in show biz (a biz I have since forsaken). Though we spent much time chatting esoterically and though both enjoyed the knowledge we shared, my end of the bargain was not my mind. Since I usually did the chiding, I consequently did everything possible to make the bargain more equitable. Though he was a genius, he was also quite a slob. So I would clean the dishes and cook breakfast and dinner. (Cleaning the apartment was impossible; nothing ever went anywhere—after ten years he was still moving in.) We even played two-piano versions of concertos. We both enjoyed this immensely, but I always knew I was there for another purpose and that knowledge made him neither a friend nor lover. This was made blatantly evident toward the end: he would introduce me to the candidates for “future companion” with a look informing me my act was getting stale. I think I love him now, but the love comes from the pity you feel when you see someone trying to buy love and affection. Pity because buying love and affection is often unnecessary—and always impossible.

Perhaps some people must purchase by amorous adventures, and perhaps, by purchasing these encounters, the subsequent events are the more delicious. (My parents told me to never do anything gratis if you could be paid for it, because the true value of what you do will never be appreciated. But I don’t think my good Catholic parents ever intended that maxim to apply to sex.) Yet there is a great difference between seeking an amorous adventure and seeking a caring companion. One man first attempted to intrigue me with his knowledge (which worked) and then declared his intentions of doing and buying everything for me (which didn’t). Had I stayed, it would have been willful suicide by smothering. Being an opera—specifically, Maria Callas—freak was the decisive factor in my departure. He reminded me too well of a former roommate who would drink and cry himself to sleep while blaring out Maria Callas’s rendition of the “Bell Song” from Lachme. I could have told the man (not the roommate) how much I detested fanatics regardless of what it was they were fanatic about, but we and our opinions were not meant to be on an equal footing. Voicing my opinion would have transgressed the boundaries between mentor and student, benefactor and recipient.

❡

Mentors. That was the real attraction of my older “friends.” There was always something I could learn from them; they all knew something I considered important or interesting, whether it was academic or experiential knowledge. Unfortunately, they never felt that a mere prat of a boy could be sufficiently captivated by such qualities (perhaps they were right), and all began to embellish upon their appeal with quantities of money. That would end things immediately. My budding concept of being an “adult” was shattered by their protection rather than furthered by their enlightenment.

So I stopped robbing the grave and began to seek out men closer to my age. Unfortunately, these younger gentlemen had their own little quirky emanations of sugar-daddy-dom. Nothing can possibly be worse than a gay male chauvinist. Never a question of gallantry, I could smell their mental computations. “Opening the door of the taxi, uh… that’s worth one-tenth; opening the door to the restaurant… one-eighth. Let’s see now, that totals nine-tenths of a fuck.” No matter how absurd or inconvenient, I was forever being calculatedly assisted in sitting down, standing up, and being made completely uncomfortable. Furthermore, bedroom arts constituted a miniscule part of their working technique.

With this for experience, my best bet would have been to join a nunnery. This growing body of attritive experiences was making me jaded and crass before losing the smooth, dewy blush of “youth.” But practice gets perfect.

Perfection first arrived in the form of a blond-haired, blue-eyed blue-blood turned theatrical entrepreneur. Though I’m never on the lookout for blondes, they seem to be on the lookout for me. As always, while looking for Mr. Tall Dark ’n’ Handsome, I fell quietly in synch with Neil. I had been trying to stay as far away from theater people as possible, but my admiration for Neil was duly exaggerated because he thought—and not just about who’s who in theater. He was charming, effervescent, intelligent, athletic, and had a good sense of humor, just like the people in The New York Review of Books classified ads. I took him to the Cloisters on a beautiful spring day; he took me to France that summer. We combed too many spots and spent too much time together alone, and he felt as attractive alone as he did chinning with luminaries we would meet in those… interesting places. We ended our grand tour in a small town south of Biarritz. His “cottage” overlooked both the little Bay of Socoa and the larger, riotous Bay of Biscay. It was the end of August and, as at the end of the month, the waves from the Atlantic were enormous and violent in their thrashings. I watched them pound angrily against the “pile d’assiettes”—a seemingly fragile rock in the water that resembled a pile of dinner plates—and I thought about all the quaintly charming dinners at which I had forced down food that in other circumstances would have tasted terrific. I was exhausted and couldn’t wait to leave.

The position I filled was necessary, but I was not. I hated him.

I vowed never to… to do what? Feel like a fool? Worry about such insignificant details as money? Look for love from a wealthy man? My practice with Lenten vows as a child was never successful, and my adult vows are even worse.

That autumn I went up to New Haven to visit a place where I had been happy as a child. It was a silly little brown-shingled cottage off the Long Island Sound that my grandfather had built. There I had spent my early summers and had learned to swim. (My sister pushed me into the deep water from a rock and said, “You’re five. It’s time to start swimming without that dumb preserver.”) Needless to say, little glaring bits of progress had crept into Sachem’s Head. Someone was building a monstrous structure right next to our house. Despite its brash incongruity, when I met the young oral surgeon who had devoted the whole room of his hymn to modern architecture to a potted palm and a grand piano, I felt a perverse attraction toward… the house. We only spent two weeks together. He spent his weekends in New Haven with patients. I killed myself eking sweet letters, trying to figure out how to get the fur coat (which he knew I needed for the cold New England winters) back to him without his being offended.

I left him too. “I guess it’s just me. I don’t know what’s wrong. Maybe I’m just a little out of it.” Great explanation. Not even truthful. I knew exactly what bothered me: all these men wanted a position filled by someone—and the fear of a lengthy vacancy allowed that someone to be almost anyone. The fact that I was a person was nice—an added fringe benefit—but irrelevant. It was as if I were the blank in Scrabble that at first seems so special and valuable until you realize it’s a substitute for any letter and as valueless as boot. I always wanted to be the “K” (the only letter worth five), and being kept wasn't helping.

The final experience that made me swear off sugardaddies was not only the wealthiest, but also the least likely of them all.

❡

When I envision a High Life Benefactor I see an white-haired gentleman, European in outlook but a born and corn-fed American, his stature diminishes the reality of his paunch, and he appears to be amused without ever smiling. My latest benefactor had none of these attributes. Tall, slender, thirty-five, English but imbued with a pure American trashiness, quite puppyish in his enthusiasm, and… a millionaire. How nice. It should have been easy to reconcile myself to his favors. Why, then, did I struggle so to find a reason for liking him? Once again, I was disgusted by the callousness of it all.

Before meeting James I knew three things about him: that he had a strikingly handsome, full-time lover; that being lovers never stopped them; and that James was a millionaire. I would hate being described in those terms—an intriguing description that says absolutely nothing (well, millionaire says something). I was determined he would become a person for me, that these superficial characterizations would disappear, that I would be his friend and not a mere recipient of his favors.

Relegated to an ancillary position within his corral of young sycophants, disgust won the first round of my crusade. He made no effort to be anything but trashy and rich. He would jokingly describe how his lover, being so exquisitely attractive, would lure pretty young men back to their lair where James, the dirty old man, would jump out of hiding and pounce on the fresh blood. Yet it was James I found attractive. His lover is perfectly beautiful—suspiciously beautiful. Models belong in magazines. How odd, I thought, that James should do such disservice to his physical appeal. Surely many people must have found him attractive, or had former encounters totally convinced him that his only trump was the credit card? Anyway, thirty-five years do not a dirty old man make.

My crusade was causing a good deal of frustration. I swore (I swear a lot) I would discover that shining nimbus of human warmth which he, too, must possess. But difficulties constantly blocked my investigation, for James rarely spent any time alone with me, except in bed (and sometimes not even there). Whatever time we had outside the bedroom was shared with various members of a large entourage—male, female, rich, poor, influential, sycophantic. Topics of discussion were matters that, at best, I do not feel strongly about. Hotel dropping (not even place dropping) never truly fascinated me. Since he hadn’t a piano, I couldn’t register my presence and annoyance by playing and singing cocktail music.

We would plan a lunch or dinner or whatever for two, and at the last minute James would surprise me by including one, two, or ten others. Though I had, to their relief, been to Paris a few times, none had ever heard of l’Hotel Henri IV. I knew why they didn’t know it, but I couldn’t imagine burying myself with an explanation. My pouring over medieval manuscripts at the Bibliotheque Nationale did not prove to be scintillating conversation. (I forgave them that; medieval history is not a particularly winning topic.) In my consequently repressed state I went back to picking at my food. I knew there was something terrifically wrong; everyone was finished before I had made a dent in my shrimp and avocado salad. (It wasn’t even a huge chef salad which I usually order to save myself from the embarrassment of finishing long before everyone else: I’m known for inhaling any food put before me.) Yet during all of these group encounters James continued to insist that I travel with him and around the globe with him. Why? If he liked my company so much, why was he continuously taking cover from me behind a phalanx of friends and acquaintances? The idea of "just the two of us" spending a number of days or weeks together anywhere horrified me. Why should I hop a plane in order to read (that’s what I’d wind up doing)? And I had no intention of going somewhere with him as his “well, I always have…” should he not find someone cuter.

Our first solo dinner was a complete bust. Solo only because his out-of-town friend bowed out at the last minute. The excellent and rather charming restaurant I chose had virtually no other diners, and the cavernous chill transformed my desired conversation into blind-date chat. I ate my usual alacrity; he praised the sauce on the veal, and the waiter sneered at me when—in my low-keyed, friendly fashion—I said I would enjoy eating the whole dessert tray. The waiter found me vulgar; I found dinner a disaster.

At our second intimate rendez-vous, I was determined to scotch the works. I hated feeling stupid and cute, as if I were still in that category of “children are to be seen and patted.” Yet before I could hit him with my “whiff of grapeshot” he began to open up—about himself, about liking me and actually considering me to be his friend. Previously he had been very tight-lipped, but now my questions began to receive answers freely given. At long last I could formulate a real description of him.

❡

At long last, I who usually form an instant opinion and accept or dismiss people on that basis, decided to give James a second, third, tenth chance to alter my initial opinion. Sinkingly, I realized that his wealth had played the greatest part in my crusade. I noticed something else that irked me: James had become so accustomed to having some "perfectly lovely young chap" around that he assumed all of them enjoyed playing house-boy to his sugardaddy. When he began to parade the presents and the trips and the money before me, he also expected me to execute my part in the farce with gusto.

No.

Had it not been for the odious casting, I probably would have left him quietly as I had all the others. Instead, being sufficiently shocked and self-righteously disgusted—not only with James, but with my shoddy excuse for a crusade—I launched into a diatribe that commenced with the tenuous state of our friendship and probably ended with the desolation of the human condition. He listened, gave it just consideration, smiled sadly, and said, “I never thought of it that way.” No, why should he? Everyone else had been only too glad to play his game—thinking the joke was on James.

We’re friends now. I’m also riding the subway again.

I’m still not sure who the joke is on. ❡