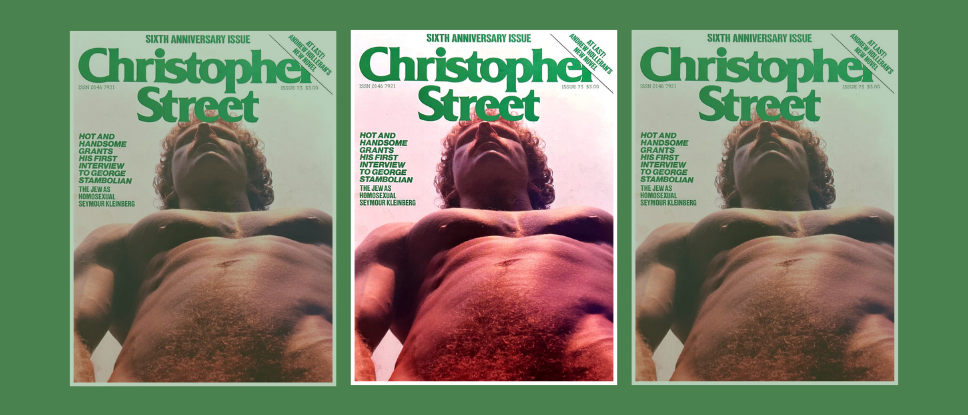

This article appeared in the June 1982 issue of Christopher Street, on pages 60-61.

A Boy’s Own Story

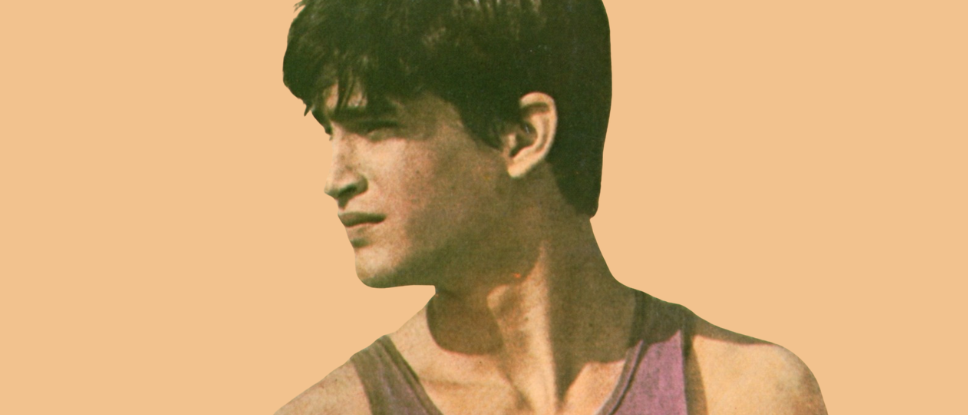

Edmund White

E.P. Dutton, Inc.

218 pages, $13.95

EDMUND WHITE IS TO the contemporary novel what Fabergé was to the egg: a craftsman whose exquisite surfaces are breathtaking in themselves, until one discovers an even richer, more wonderful treasure at the heart of the gift. To say that this novel is his most accessible yet indicates no retreat from the high standards that prompted Susan Sontag to call him “one of the outstanding writers of prose in America today.” Rather, White has turned his acuity, the literary equivalent of haute cuisine, to a meat-and-potatoes subject: the story of a boy growing up.

The first-person protagonist of A Boy’s Own Story lives in the Middle West in the Fifties. Suntanned kids on sun-drenched lakes in Sunkist ads are today’s image of typical teens; but White’s adolescence is a twilight time in which “the teenager” is as unrecognized a cultural entity as “the homosexual.” The novel’s unnamed narrator is both. Self-conscious, sensitive, bright, and wealthy, he is the only son of a nighthawk tycoon whose idea of manliness “was not discussable, but had it been, it would have included a good business sense, ambition, paying one’s bills on time, enough knowledge of baseball to hand out tips at the barber shop, a residual but never foolhardy degree of courage, and an unbreachable reserve.” The boy’s mother drinks, dotes, leans on her son for emotional support. His older sister taunts him as a “sissy.” The narrator knows each of them, with a memory for detail and a lucidity that brings back with aching beauty the perceptual intensity of youth.

Of himself, however, the young man knows little, except for his explosive potential. “I was three people,” he recalls; “the boy who smelled bad when I was with my sister; the boy who was wise and kind beyond his years when I was with my mother; but when I was alone not a boy at all but a principle of power, absolute power.”

The novel describes the boy’s search for the models who will explain to him who or what he is (a progress not unlike the feverish search of the amnesiac narrator in White’s first novel, Forgetting Elena). He summers with father, winters with mother, sojourns in prep schools and summer camps. He meets a delightful range of improbable, perfectly believable characters: a speed-freak psychiatrist, a fourteen-year-old Nazi, a preening, worldly, reactionary priest. He has sexual experiences with a playmate, a hustler, an “oversexed” pariah with a 24-hour erection. And he discovers that the gateway to adulthood is not the achievement of love or the courage to cope, but the capacity (and the power) to betray.

There are lushly romantic moments in the novel: a speedboat ride on a dark lake, privileged moments with a first, unrequited love, dreams of on-stage triumphs in dramatic productions at camp. But A Boy’s Own Story is no romance; rather, it evokes with almost scientific precision the adolescence whose poles are loneliness and aloneness.

It is noteworthy that White’s novel recounts no situations where the discovery of sex or sexual orientation are in themselves keys to discovering the wide world “out there.” His characters inhabit no cultural backwater (unless America in the Fifties can be considered a gigantic one). And sex is not a shorthand form of liberation from anything. In fact, the narrator’s symbolic, sexual act of initiation at the book’s climax is in direct imitation of the cruelty and manipulativeness that characterize his almost unbearably sexually “normal” father.

A Boy’s Own Story, then, speaks to the experience not only of those who, like White, are gay and male, but of all who have “grown up.” It brings back the anguish, the powerlessness, the boredom, and the dreams shared not only by those with “different” desires, but by all who experience the bumpy process of covering the child’s essential, isolating uniqueness with the borrowed garments of socialization. There is, however, a special message here for gay people. Thirteen years after Stonewall, it is increasingly difficult to recall a time when the only models for gay life were the wretched deviants in textbooks or the shadows cruising parks with names like Fountain Square, Lafayette Park, or (more colorfully in my own hometown) King Philip’s Stockade. In his most affecting work yet, Edmund White provides an unforgettable souvenir of that lost time. A Boy’s Own Story is part of our, and everybody’s, history. ❡