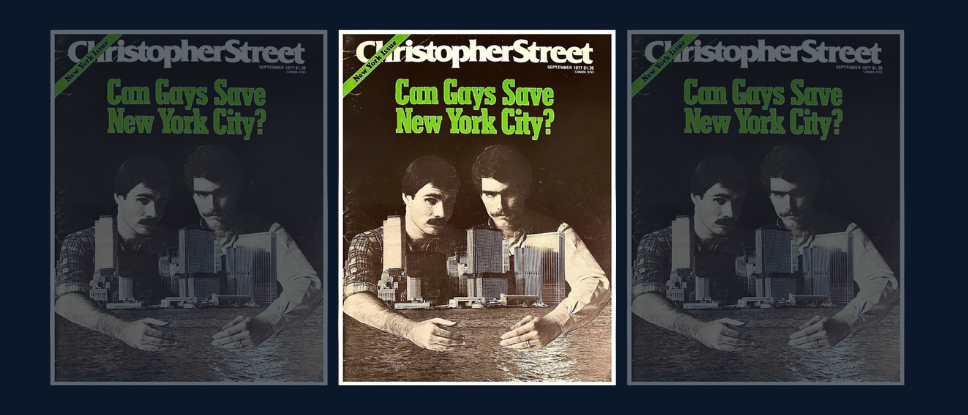

This article appeared in the September 1977 issue of Christopher Street.

For me New York gay life in the seventies came as a completely new beginning. In January 1970 I moved to Rome after having lived in the Village for eight years. When I returned ten months later to the United States, an old friend met me at the airport, popped an “up” in my mouth, and took me on a tour of the back-room bars. In Rome there had been only one bar, the St. James, where hustlers stood around in fitted velvet jackets; the only sex scenes had been two movie theaters, where a businessman with a raincoat in his lap might tolerate a handjob, and the Colosseum, where in winter a few vacationing foreigners would cluster in nervous, shadowy groups. For real sex in bed I had to rely on other Americans and upper-class Italians, the only ones who didn’t regard love between men as ludicrous. (I had an affair with an impoverished Florentine baron who was writing his dissertation on William Blake.) On the streets, even when shopping or going to lunch, I dressed in a fitted velvet jacket and kept my eyes neutral, uninquisitive. Today, of course, Italy has an active gay-liberation party, large annual gay congresses that choke on Marxist rhetoric, and articles in Uomo about gay fashions that purport to be without any historical precedent (actually they’re just overalls or unironed shirts). But when I lived there Rome was still a bastion of the piccolo borghese and miniskirts were considered scandalous.

I have a disturbing knack for doing what used to be called “conforming,” and by the end of my Roman holiday I was hiding my laundry in a suitcase (to avoid the disgrace of being seen—a man!—carrying dirty shirts through the streets), and I was even drifting into the national sport of cruising women. My assimilation of heterosexuality and respectability made new New York all the more shocking to me. My friend took me to Christopher’s End, where a go-go boy with a pretty body and bad skin stripped down to his jockey shorts and then peeled those off and tossed them at us. A burly man in the audience clambered up onto the dais and tried to fuck the performer but was, apparently, too drunk to get an erection. After a while we drifted into the back room, which was so dark I never received a sense of its dimensions, although I do remember standing on a platform and staring through the slowly revolving blades of a fan at one naked man fucking another in a cubbyhole. A flickering candle illuminated them. It was never clear whether they were customers or hired entertainment; the fan did give them the look of actors in a silent movie.

All this was new. At another bar, called the Zoo or the Zodiac (both existed, I’ve just confused them), a go-go boy did so well with a white towel under black light that I waited around till he got off—at 8 A.M. In the daylight he turned out to be a bleached blond with chipped teeth who lived in remotest Brooklyn with the bouncer, a three-hundred-pound man who had just lost fifty pounds. I was too polite to back out and was driven all the way to their apartment, which was decorated with a huge blackamoor lamp from Castro Convertible.

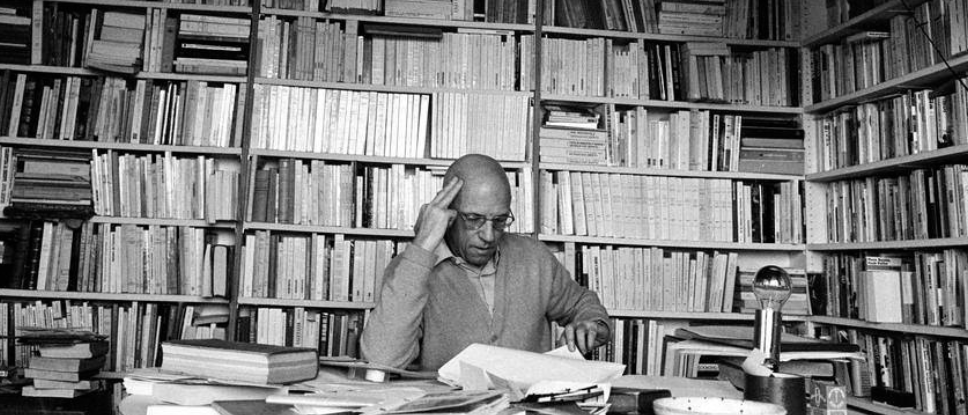

For the longest time everyone kept saying the seventies hadn’t started yet. There was no distinctive style for the decade, no flair, no slogans. The mistake we made was that we were all looking for something as startling as the Beatles, acid, Pop Art, hippies and radical politics. What actually set in was a painful and unexpected working-out of the terms the sixties had so blithely tossed off. Sexual permissiveness became a form of numbness, as rigidly codified as the old morality. Street cruising gave way to half-clothed quickies; recently I overheard someone say, “It’s been months since I’ve had sex in bed.” Drugs, once billed as an aid to self-discovery through heightened perception, became a way of injecting lust into anonymous encounters at the baths. At the baths everyone seemed to be lying face down on a cot beside a can of Crisco; fistfucking, as one French savant has pointed out, is our century’s only brand-new contribution to the sexual armamentarium. Fantasy costumes (gauze robes, beaded headache bands, mirrored vests) were replaced by the new brutalism: work boots, denim, beards and mustaches, the only concession to the old androgyny being a discreet gold earbob or ivory figa. Today nothing looks more forlorn than the faded sign in a suburban barber shop that reads “Unisex.”

Indeed, the unisex of the sixties has been supplanted by heavy sex in the seventies, and theurge toward fantasy has come out of the clothes closet and entered the bedroom or back room. The end to role-playing that feminism and gay liberation promised has not occurred. Quite the reverse. Gay pride has come to mean the worship of machismo. No longer is sex confused with sentiment. Although many gay people in New York may be happily living in other, less rigorous decades, the gay male couple inhabiting the seventies is composed of two men who love each other, share the same friends and interests, and fuck each other almost inadvertently once every six months during a particularly stoned, impromptu three-way. The rest of the time they get laid with strangers in a context that bears all the stylistic marks and some of the reality of S and M. Inflicting and receiving excruciating physical pain may still be something of a rarity, but the sex rap whispered in a stranger’s ear conjures up nothing but violence. The other day someone said to me, “Are you into fantasies? I do five.” “Oh?” “Yes, five: rookie-coach; older brother-younger brother; sailor-slut; slave-master; and father-son.” I picked older brother-younger brother, although it kept lapsing into a pastoral fantasy of identical twins.

The temptation, of course, is to lament our lost innocence, but my Christian Science training as a child has made me into a permanent Pollyanna. What good is coming out of the seventies? I keep wondering. Well, perhaps sex and sentiment should be separated. Isn’t sex, shadowed as it always is by jealousy and ruled by caprice, a rather risky basis for a sustained, important relationship? Perhaps our marriages should be sexless, or “white,” as the French used to say. And then, perhaps violence, or at least domination, is the true subtext of all sex, straight or gay; just recently I was reading an article in Time about a psychiatrist who has taped the erotic fantasies of lots of people and discovered to his dismay that most of them depend on a sadomasochistic scenario. Even Rosemary Rogers, the author of such gothic potboilers as The Wildest Heart and Sweet Savage Love, is getting rich feeding her women readers tales of unrelenting S and M. The gay leather scene may simply be more honest —and because it is explicit, less nasty—than more conventional sex, straight or gay.

As for the jeans, cowboy shirts and work boots, they at least have the virtue of being cheap. The uniform conceals the rise of what strikes me as a whole new class of gay indigents. Sometimes I have the impression every fourth man on Christopher Street is out of work, but the poverty is hidden by the costume. Whether this appalling situation should be disguised is another question altogether; is it somehow egalitarian to have both the rich and the poor dressed up as Paul Bunyan?

Finally, the adoration of machismo is intermittent, interchangeable, between parentheses. Tonight’s top is tomorrow’s bottom. We’re all like characters in a Genet play and more interested that the ritual be enacted than concerned about which particular role we assume. The sadist barking commands at his slave in bed is, ten minutes after climax, thoughtfully drawing him a bubble bath or giving him hints about how to keep those ankle restraints brightly polished. The characteristic face in New York these days is seasoned, wry, weathered by drama and farce. Drugs, heavy sex, and the ironic, highly concentrated experience (so like that of actors everywhere) of leading uneventful, homebodyish lives when not onstage for those two searing hours each night—this reality, or release from it, has humbled us all. It has even broken the former tyranny youth and beauty held over us. Suddenly it’s okay to be thirty, forty, even fifty, to have a streak of white crazing your beard, to have a deviated septum or eyes set too close together. All the looks anyone needs can be bought—at the army-navy store, at the gym, and from the local pusher; the lisped shriek of “Miss Thing!” has faded into the passing, over-the-shoulder offer of “loose joints.” And we do in fact seem looser, easier in the joints, and if we must lace ourselves nightly into chaps and rough up more men than seems quite coherent with our soft-spoken, gentle personalities, at least we need no longer be relentlessly witty or elegant, nor need we stand around gilded pianos bawling out choruses from Hello, Dolly, our slender bodies embalmed in youth, bedecked with signature scarves, and soaked in eau de cologne.

My enthusiasm for the seventies, as might be guessed, is not uninflected. Politically, the war will not take place. Although Anita Bryant has given us the temporary illusion of solidarity, gay liberation as a militant program has turned out to be ineffectual, perhaps impossible; I suspect individual gays will remain more loyal to their different social classes than to their sexual colleagues. The rapport between gay men and lesbians, still strong in small communities, has collapsed in the city, and this rupture has also weakened militancy. A general American rejection of the high stakes of shared social goals for the small change of personal life (study of the self has turned out to be a form of escapism) has left the movement bankrupt. But in the post-Stonewall decade there isa new quality to New York gay life. We don’t hate ourselves so much (although I do wish everyone would stop picking on drag queens; I at least continue to see them as the Saints of Bleecker Street). In general we’re kinder to our friends. Discovering that a celebrity is gay does not automatically lower him now in our eyes; once it was enough to say such-and-such a conductor or pop singer was gay for him to seem to us a fake, as inauthentic as we perceived ourselves to be. The self-acceptance of the seventies might just give us the courage to experiment with new forms of love and camaraderie, including the mariage blanc, the three- or four-way marriage, bi- or trisexuality, a community of artists or craftsmen or citizens from which tiresome heterosexual competitiveness will be banished—a community of tested seaworthy New Yorkers. ❡