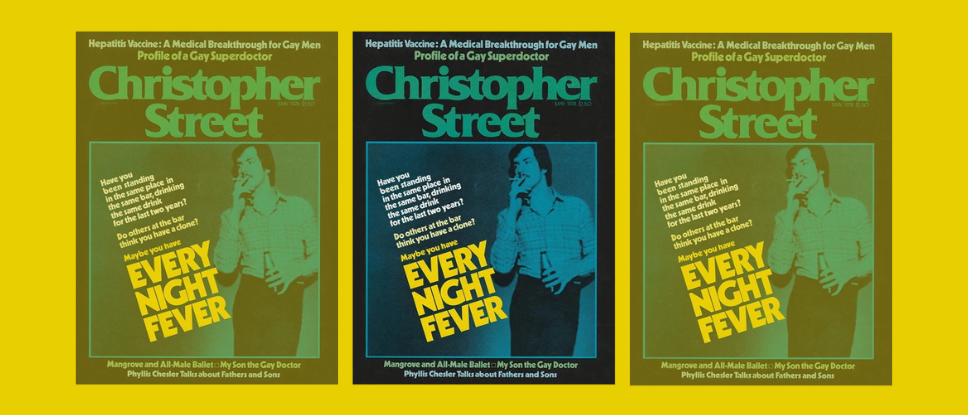

This article originally appeared in the May 1978 issue of Christopher Street, on pages 4-8.

IT'S 11 P.M. You’ve worked all day, crawled home, made dinner, tried to reach a few friends by phone, and now you’re sitting alone in your apartment watching the paint peel off the walls. You decide to turn on the TV, but realize you know this Burns and Allen rerun by heart. You reach for your copy of Hollywood Babylon. It crinkles into yellow pieces from overuse. Out of sheer boredom and a need to be somewhere—anywhere—else, your feet start shuffling, your hips start swaying, and you hear the distant sound of a thumping disco beat. You’ve got: Every Night Fever.

John Travolta had something like it in Saturday Night Fever. He had to go to the disco every Saturday night. It was a physical release, a chance to meet with friends and get attention, to feel real in a thoroughly unreal environment. It was a fun, ego-building escape from his workaday life as a nobody. Take all of that and multiply it by seven on the fanaticism scale—or better yet, imagine a week in which every night is Saturday—and you’ve got an idea of what every night fever is all about.

Randy Heimers has every night fever. He jokingly says he could count on his four limbs the nights he’s been absent from the Barefoot Boy in the past year. Practically every night at around 11:30, the going-out ritual begins: Randy washes, changes, puts every hair into place with more care than he takes preparing to go to work in the morning. At around 11:55 he leaves his apartment and arrives at the Barefoot Boy, three blocks from his doorstep, about ten minutes later. At 1:30 he leaves. On weekends, he says, he doesn’t mind going somewhere else, but usually he can be found in the same spot at the same time.

It takes either extreme exhaustion or illness to halt the routine, and anything else is a small hindrance indeed. In the midst of the worst snowstorm of the decade, Randy trudged through mounds of snow to get to Barefoot Boy; when his father visited from upstate, Randy was relieved when their dinner appointment ended early enough for him to get to the disco for his nightly appearance.

Randy, who has a secretarial job, enjoys the general sense of excitement, of being where the action is. “It’s the most enjoyable part of my day. Often I think, ‘This one hour makes the other twenty-three hours worth going through.’ When I feel depressed, just hearing the music energizes me. The music and the cruising are equal parts of the same experience, which is very erotic. It’s the people. It’s getting out of the house for fresh air, meeting people, seeing people you know…. At the end, I never want to leave.”

At Barefoot Boy, Randy generally stands in the same spot just to the left of the right entrance to the dance floor. He shakes to the music in a subtle invitation to dance. Often he prefers standing amidst the people and swirling lights and deafening music to chatting with friends at the bar. It’s a sacred time for him and he doesn’t want to be disturbed. On weekdays, he stays until 4 a.m., when they play Liza Minnelli’s “New York, New York” and turn up the lights—a moment he hates.

❡

The need to be in a group of people seems to be the main motivation for continually going out—whether it be specifically to meet new friends, to socialize with old ones, or to cruise for a pickup. Different people interpret the urge differently. To the people around them, the every-nighters are simply running away from themselves. To the every-nighters, they’ve made a realistic choice to spend their free time in a lively atmosphere rather than sit home alone.

“They’re looking for a new experience,” says Victor, a waiter at New York’s posh Studio 54. “Circulating with people means anything can happen. It’s easy to get into it if you need an escape. You don’t have to think. It’s like a drug.”

“Going out is a false cure for loneliness,” says Mike, the coat-check person at Barefoot Boy. “Anyone who does it all the time has just lost interest in it. I don’t see that’s constructive in it at all.”

“It’s mostly social,” explains a twenty-year-old aspiring actor from Buffalo who used to be an every-nighter, and then a waiter, at the Hibachi Room there. “The Hibachi Room draws you in, for some reason. Once you become a regular, you didn’t want to leave. It became a family. You’d see the regulars on the street and immediately say, ‘Hibachi Room.’ It was so much fun. They’d put on Hello Dolly and I’d go up on stage and act out the lyrics. It was a ball.” He paused for a second, checking himself. “There were other things to do, but I got into a rut. I would sometimes say, ‘Can’t we please just sit home and watch television?’ Regulars always say, ‘Isn’t there something else we can do?’—but they don’t. Still, I never regretted going.”

John Koch, manager of the Ninth Circle bar in Greenwich Village, also cites the security of being a member of a clique as a motivating factor for every night fever. “Most of the people who come here,” he says, “know that so-and-so’s going to be here at such-and-such a time. There’s security in that.” Koch added that for a lot of the people—about half the regulars—the motivation for going out is purely sexual. People with an endless capacity for quick sex, or just low batting averages, go out night after night looking for someone to make their beds less empty–at the same time making bars such as the Ninth Circle crowded every night of the week. “When I go out,” says a middle-aged, bearded man who frequents the place, “I go out to cruise. If socializing is all that comes of it, I’m not tremendously disappointed. But I’m here to cruise.” He added with a shy smile that he used to go out every night until he moved to northwestern New Jersey—“The best thing I ever did for myself.”

❡

Cruising is also the motivating force for twenty-year-old student Aaron Silverberg, but with an unusual twist. Aaron goes out to bars more to be looked at than to be picked up. He says he’s struck by every night fever, often against his will, whenever he comes down from Cornell to New York on vacation. “Sometimes I go out even when I don’t want to. It becomes a habit after a while. I never even think about it. Last summer, I went out every night. I was living in a tiny room and I couldn’t sit at home and read. Of course, I didn’t have to have that apartment.”

Without pausing, Aaron—an athletic but studious-looking biochemistry major with a permanent smile on his face—narrowed the list of possible motivations to one. “I need to have people pay attention to me. People stand around and look at one another. It makes me feel attractive. I usually want to go home with someone–but if I turn somebody down, it’s a feather in my cap. I feel I have to impress people. If one or two guys in the Ramrod know me, it’ll lead to a wealth of connections. Soon I’ll know everyone in New York.”

Although Aaron said he would rather have been reading or seeing a movie, he found himself going to the same rounds of Village bars every night—the Ninth Circle, Julius’s, Ty’s, and then the Ramrod—and that most nights he returned home depressed. “I don’t think it’s a good thing to do the same thing every night,” he says, smiling the whole time. “There’s always different people, but it’s the same scene.” His smile broadens. “Still,” he says, “there’s always a chance that one of those nights you’ll go home with someone wonderful who’ll change your life.”

Aaron looks admiringly at businessmen standing around the bar at Julius. “When I dream about my future, I’ll come to New York and find a job like these guys in business suits have. They all come here and are talking with friends. It seems like a pleasant existence.” But what he really wants, he says, after more thought, is “to be settled, to see if I can really keep out of bars.”

He brushes his hair with the back of his hand and looks slightly miffed, but still smiles. “I’m going bald. You lose your sexual attractiveness as you go bald. Sometimes it worries me, but I’m optimistic.”

Going out constantly may have helped Aaron’s sex life, but he feels it’s also drastically hurt his social life. “You don’t want to bother with having any long, complicated conversations with people. Last summer I didn’t even want to go home on Sundays to visit my parents. I didn’t want to be talking.”

“Someone once said to me, ‘Don’t ever have a relationship with someone you meet in a bar or disco,’” says a one-time habitue of Twelve West. “They can’t escape to anything else.”

This is all myth, according to one virtual resident of Uncle Charlie’s South. Just because people enjoy going to bars doesn’t mean they’re mindless, he argues. “In fact, they’re generally more interesting and worth meeting than people who don’t go out.”

Perhaps that’s true. Perhaps every-nighters aren’t any less visible as social creatures outside the bar than anyone else. But consider the lot of the friend of the every-nighter. He’s walking along with his feverish friend after, let’s say, seeing a play together. Suddenly the every-nighter says goodbye, darts for the nearest subway station, and disappears. The friend looks confused, checks his watch, and realizes that going-out time has struck. “It’s one thing to be ditched for another person,” he mutters, “but to be ditched for a place—that’s something else.”

The next day, the feverish disco-hopper relates to his friend how uneventful the night turned out to be—empty, dead, boring—and asks incredulously why the friend didn’t want to come along. The friend might conclude that every night fever is less a blessing than a curse—for him, anyway.

❡

Steve Rudolph says he used to consider going out more important than being with friends or having time alone. But not anymore. “I was very bored with my life,” he explains. “My job at CBS was very routine, and I refused to let the weekend stop for me. I found the need to fill up my life with as much partying as possible. I used to feel I’d miss the man of my dreams if I didn’t go out.” What happened when he didn’t find the man of his dreams? “It was frustrating at first. I wasn’t finding what I was looking for. Then I changed my attitude. I started looking to have fun, to make connections. That was destructive, too. I’d meet people in much higher financial brackets at Studio 54. To them, a bottle of champagne was nothing. It made me feel terribly insecure.

“I was filling gaps in my life, filling voids. People have to be in the limelight, they have to be in the right place at the right time. It’s the old saying, ‘Everyone’s a star at a disco.’ Ninety percent of the people at Studio 54 are not real. They’re not the same on the inside.”

Steve says he’s much more content with his work now—he does per diem work for CBS and works weekends at the Institute for Human Identity. “Now I’m so tired I can’t go out. I feel generally more fulfilled. Years ago, I could not face being alone. Now I like being with myself. I can just go out to dinner with a friend, watch Saturday Night Live, and then go to sleep.”

Steve looks back on his every night fever with mixed feelings. “When I first came out of it, I felt resentful. It’s the old Sunday morning ritual: ‘What the hell did I do that for?’ Now I say, ‘It’s a stage I had to go through to get where I am now.’”

Chuck Silverstein, Steve’s coworker at the Institute for Human Identity and the psychologist who co-authored The Joy of Gay Sex, takes an even dimmer view of every night fever. “Anyone who has to get out of the house every night is probably someone who can’t withstand the feeling of being alone,” he says. “I wouldn’t want to differentiate between going to discos or bars and having dinner with friends. It’s the same motivation—fear of being alone.”

Silverstein goes even further when he says that anyone who’s involved repeatedly in some kind of physical activity such as disco dancing is “dissolving all the anxiety they have about themselves into physical activity. It’s the old adage, ‘If you want to jerk off, run around the block.’ You can run it off or dance it off. It’s a way of avoiding problems. Even if they don’t actually dance, it’s the same thing. It’s all in the preparation—dressing up and showering. There are a lot of fantasies involved. It’s a whole ritualistic scene.”

What’s ignored in this view, perhaps, is that releasing anxieties through going out is unquestionably better than keeping them pent up. Few every-nighters would say that their anxieties drive them out of the house; they just want to have a good time and to hell with psychologists. Try telling them what a noted anti-gay psychiatrist said—that people who go out every night are “wasting their time in meaningless socializing and meaningless sex”—and they laugh it off and continue dancing.

One regular at Barefoot Boy says he knows going out may be bad for him in the long run. “Judgments anyone else may make on my behavior,” he says, “don’t mean anything.” David, a waiter there, points to him with a slight sneer as he passes. “He belongs to a certain type that always comes here. He never buys drinks, he looks like a total noodnik, and he usually goes home alone. He never even checks his coat.” David laughs uproariously, then stops. “This scene shouldn’t be portrayed as a boulevard of broken dreams, though.” The every-nighters come out of necessity, he argues, and they have good reason to be there. “They’re persevering. They want lovers,” he says. “They want to be around people. Once you get out of college, there are so few meeting places. The only place where you’ll find a group is in a disco. It reinforces the idea that yes, there are other people out there. It’s good for these people to realize that.” As for himself? He smiles. “I like the sanctity of the home. I’d rather curl up with a good book, the Late Show, and my lover.”

❡

It is a Sunday morning in March. Four a.m. The manager of Barefoot Boy is about to lock the door for the last time. The club, soon to re-open under another name, is about to pass into history. People straggle out in groups, laughing, singing, drunkenly avoiding the sad consequences of the occasion. Eventually, Randy Heimers emerges, his face drawn in disbelief. “The Barefoot Boy is dead,” he says with mock pomposity filled with obvious hidden pain. “I should go into mourning. I’ll wear my black jeans.” He surveys the facade, the canopy, the exiting patrons. “This place should be a shrine. We should place flowers on the grave.” He’s cracking jokes, but not laughing. “I’m glad I went for the sad last day. It’s the end of a long era. When I think I’ve been going for two and a half years…” He doesn’t complete the thought.

“Now I’ll just sit around. . . . No, I have to go out. I do have every night fever.”

The following night, Randy is standing on the left side of the dance floor at Harry’s Back East. ❡