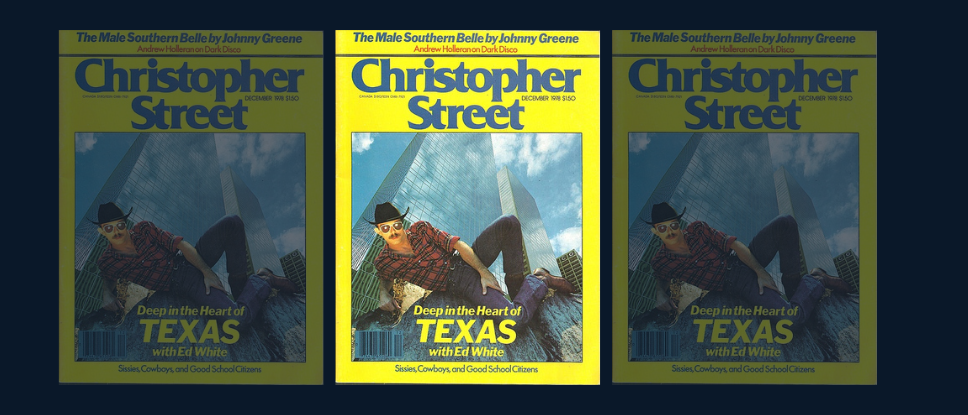

This article appeared as the cover story of the December 1978 issue of Christopher Street under the title, “Texas: Sissies, Cowboys, and Good School Citizens.”

The day I flew to Houston last July I was hung over and exhausted. I had had too much stimulation and too little sleep during a hectic week in New York and was looking forward to hiring a car, heading toward some sedate Texas hotel or other, and curling up for the night; I thought vaguely of buying cool summer pajamas and ordering toast and tea from room service. I was a bit surprised to notice that the plane was packed at one in the afternoon on a Tuesday, but I didn’t become alarmed until the French engineer beside me said that a room might be hard to come by. “We’re flying in from all over the world for a petrochemical conference. There are eighty of us. My assistant has been on the phone for a week searching for rooms somewhere, anywhere, but as of now we still have three vice-presidents on cots in a single.”

Fraternal and amusing as those arrangements sounded, they didn’t augur well for me; I have always, when traveling, counted on fate to play the resourceful concierge. “But Houston is like that,” my engineer said. “Always overcrowded, the whole world standing, hat in hand, at the door, wanting in. We may laugh at it—it is frightfully vulgar—but we are its clients.” He turned back to his copy of Voltaire’s Micromegas. A bit later he explained that he was “really” a writer; though he’d been working for thirty years as an engineer, that was just a curtain-raiser to the main piece, his upcoming career as an author and thinker. Having myself been a teacher, truck driver, editor, and PR man, I understood the delay.

In the airport I was cruised by two men and asked them where I should stay. One of them recommended a motel where he had lived for a few months after first arriving in Houston. It was, he said, near the action, only somewhat “infested,” and quite cheap. The other man expressed mild surprise that I was visiting Houston for “pleasure.” None of the rental services had a car; the attendants smiled wearily at the naive request. Nor could I find a taxi. At last I resorted to the bus—fortunately, since the airport is a costly hour and a half away from the city. (The optimistic Houstonians expect that one day the city will reach out to the airport. Certainly most of them are predicting that by the twenty-first century their city will outstrip all others in size, wealth, and power.)

As I rode in I observed through the tinted panes empty fields out of which erupted, here and there, not the expected house or store but an imposing bronze skyscraper, jutting up like a bold exclamation point following a bland, run-on sentence. Past me flew miles of mobile homes for sale, those shingled and windowed rectangular boxes longing to lose their mobility and sink peacefully into a plot and join their pipes to those in the raw earth. Fields of weeds, dusty trees, the odd skyscraper, and then a motel; its raised billboard proclaimed not “Welcome Engineers” but “Waitress Wanted—Top Pay—Bellboys, Too.” We swept past an extensive development of what I believe are called “town houses” (terraces of rowhouses), all crunched under top-heavy mansard roofs. One ambitious design had even managed to pull the mansarding down nearly to the ground, turning the top three floors into stacked garrets peeking out at the weeds and skyscrapers through dormer windows; only the ground floor had a clapboard siding, painted the pale orange of an unlicked popsicle. The odd proportions reminded me of a little boy half hidden by his father’s giant sombrero. But all buildings in Texas give an overall sense of prefabricated units that have been landed on the terrain. They are pure expressions of will and bear no relationship to the surroundings. Even the most modern space capsule, however, is awarded a name out of history. If there is a restaurant in the building, it too will have a historical name, though not necessarily of the same period. Thus, we will have Bluebeard’s Dungeon in the Queen Victoria, or the Old West Saloon in the Forbidden Palace.

Finally the city itself materialized. My first glimpse of it was blurred by the sudden, cloacal collapse of a searing, five-minute rain. It was as though the devil had decided the infernal heat needed just a soupçon more of humidity to become the sort of torture he had had in mind. The buildings were indifferent to the miasma; with their spotless white mullions and smoked glass or blue, mirrored skins or long, tall merlons flanking windows no wider than a medieval archer’s crenel, they were as alien as space stations deposited on hostile Mars. One suspected they were self-sufficient, tenantless (there were no pedestrians in sight), and fully computerized, that if they retained windows at all, they did so only as a courtesy nod to the past.

Later, when I toured the business district, I discovered why no one was visible: all the buildings are interconnected by air-conditioned second-story covered walkways or underground tunnels. The major buildings are the headquarters of oil companies, and all but one of them had been erected since 1968. The latest development is the Houston Center, which will comprise twelve buildings (including five thousand apartments). The architecture is so advanced that it was used with no modification as the set of the sci-fi movie Logan’s Run. The floors and walls here are pink Texas granite; on a balcony one sees a bent aluminum tube (sculpture? exhaust?); the escalators are outlined in cold white neon. One glimpses into a restaurant filled with foliage and twinkling lights and sees flirtatious couples huddled over little tables—no, it’s a bank, and those are desks. I kept thinking that there’s no reason Houston should have skyscrapers at all; land isn’t that valuable here yet. But of course, for Houstonians the buildings are their Tinker Toys. They contemplate the business district from a distance and say, pointing, “Now you need another black one over there, maybe a trapezoid. And then square that corner off with a nice silver one.”

❡

The bus deposited me at a terminal where a long row of brightly colored telephones promised to connect me instantly with a wide assortment of hostelries (there are, it turns out, few hotels, and they are listed in the Yellow Pages under “motels”). Every place was full, including the motel the guys at the airport had recommended. In a panic I decided to apply in person to their motel. I ordered a taxi and after a long wait obtained one. At the motel office I was for some reason accepted; I was directed to the sixth and last building of the complex, a good half-mile down a blinding gravel service road. Behind the motel were parked several semis; hanging over the balcony railing were trim black women in micro-skirts, plastic boots, and bouffant wigs. The rather dour whites I passed kept addressing one another as “Brother This” and “Sister That.” Saudis in turbans were streaming into the restaurant. Dazed by the heat and feeble to begin with, I had difficulty reconciling these elements with one another. Was I feverish?

As it turned out, the motel was notorious as a hangout for hookers who serviced truckers. They and their stylish pimps occupied half the rooms; all night long men were tapping on my door and imploring Judi to “open up.” The rest of the place had been rented by Jehovah’s Witnesses; there were fifty-five thousand of them convening in Houston for a powwow at the Astrodome. Hookers and Witnesses rubbed shoulders all week in the coffee shop, which was also popular with Arab students who’d come to Houston to master the mysteries of petroleum technology. To add to the fun, Barnum and Bailey (the six o’clock news reported) had also descended on Houston—elephants, like overheated tanks, had rumbled through the empty streets that afternoon, their massive bulks hosed down with cold water every block or so to keep their radiators from boiling over. Agitated by so much that was mal assorti, I left my room, with its moderate infestation of roaches and water beetles and its two double beds, both their backs broken, and sallied forth for a walk—only to discover that the town fathers had neglected to give sidewalks to this neighborhood. There I stood, far from a bus route and unable to walk or rent a car or hail a taxi, and watched the traffic hurtle merrily by. I contented myself with an overdone steerburger, a rather sweet little covered basket of biscuits, and a large milk as I eavesdropped on Arabs, whores, and the religious, those poor souls subscribing to a regimen of no smoking and only light drinking in a city where Mexican grass sells for $12 an ounce and more beer than water is consumed in the summer months, a place that has the third highest rate of alcoholism in the nation and a crime rate that rose 12 percent in the first six months of the year. Houston also has no zoning laws, and as a consequence a church can be squeezed in between a shopping center and an adult bookstore and peep show (it is a city of unlikely company). Although one group is campaigning to keep the porn shops at least two thousand feet away from the churches and schools, the proposal for such a cordon sanitaire violates the Houston charter, which grants every microbe the run of the city.

❡

Unsteady though I may have been, at ten in the evening I summoned a taxi and headed to the best leather bar in town, the Locker. There I stood in the back patio, propping myself up against a corral fence and looking out at a withered, spotlit tree. Its small leaves weren’t stirring. Along one wall was painted a large mural of cacti on the moonlit mesas, looking like disembodied rabbit ears out for a midnight stroll. At one end of the yard rose the false front of an Old West hotel, a Potemkin set where pairs of men nursed funny cigarettes. The air was sweating, dreamless, more in a faint than asleep. The men around me, conserving their energies, weren’t talking; the only vital sign was an occasional shift from foot to foot, unless that was an illusion performed by the warping heat waves.

And then, interrupting this saurian torpor, someone entered who was very much in motion. He hovered up to me, engaged me in conversation, and permitted me to buy him a beer. He was twenty-two and chubby and was experimenting with a mustache (it looked like a caterpillar paralyzed by stage fright halfway across a winter melon). All the little movements he produced (and he was as active, as rippling, as the draperies of an Ascending Virgin) arose from inner turmoil—the familiar conflict, for instance, between a desire to establish contact and a fear of being snubbed.

As he talked on, I turned my lidless eyes toward him, unscrolled my sticky tongue in a trial run, and watched my fly buzzing around another contradiction—his inclination to be flamboyant and his resolve to be reserved (one imagined him wearing a gold anklet under his cowboy boot). And then it wasn’t clear whether he wanted to seduce me or himself, for though half his talk was about sex and the possibility of having it, the rest was devoted to his Past, a plot by Dreiser written in the vivid style of Georgette Heyer. Apparently even his life, his novel, was tremulously ambiguous, as was his recital of it; he had a trick of saying something sad about himself, which elicited sympathy—and then springing on me, out of nowhere, a big, disconcerting, shit-eating grin. When he spoke, he kept himself in modest profile, but when he produced that grin, he turned toward me with shocking intimacy. He seemed to be a writer who enjoyed torturing both his reader and his protagonist, despite the fact that the reader in this case was a potential pickup and the protagonist his own immortal soul. My only fear is that I make him sound sinister; have I made it clear he was, despite the boots and mustache, that perennially endearing figure, the Southern Sissy?

“My father,” he said, “liked me, but my mother never did. She didn’t want us kids, didn’t want to cook for us—heck, didn’t even want to talk to us. My dad liked me”—and then the grin unleashed—“because he was gay. I found that out by going into his closet (no pun intended) and discovering all these dirty magazines. When I was eighteen, he died from lung cancer, and he wasn’t the smoker; my mother smokes and is still going strong. She threw me out of the house as soon as he was under the ground.” (Southern speech, no matter how casual, always lilts with little literary touches: the parallelism of “out of the house” and “under the ground,” even the old-fashioned periphrasis of “under the ground.”)

“I got a job and some credit cards. And then I just charged and charged”—the “charged” is drawn out, sung first on a high note, then on a low—“until I’d run up a bill of $15,000. I didn’t know what to do. So I fled town and came to Houston with nothing but a bag and a $5 bill.”

“And then?” I asked anxiously; I am not one of those people who believes, as Rilke did, that the world will take care of you, that its hands are under you and will catch your fall.

“It’s very easy to succeed in Houston,” he said. “In one night at a bar you can make four or five friends and they will put you up one after another. Everyone’s new here.”

“And then?”

“I went into a beauty-supply store and asked for a job. I lied and told them I had a degree in cosmetology. They put me to work that very day. Now it’s a year and three months later and I was just named the store manager.”

“How,” I asked, already suspecting the answer, “did you fake a knowledge of cosmetics?”

He seemed caught in another crosscurrent of uncertainty. His hand flew up to pat an invisible but palpable chignon, the chic saleswoman’s bun, pierced ukiyo-e-style with several pencils at odd angles, while simultaneously his voice dropped into a lower register: “I know all about that; I had a lot of... uh... friends in drag.” (The well-known “friend” strategy: “Doctor, I have this friend who’s homosexual and needs advice.”) “And what do you do?” he asked. It was his first acknowledgment that I, too, might have a life, might be more than a reader, though I suspect he was more eager to get away from the subject of drag than curious to explore my story.

“Write,” I said.

“So do I!” he exclaimed, more delighted by the coincidence than I, since I had already been perusing his work. “I’m a writer, too. I loved English in school. My favorite period of poetry was the Romantic, and my favorite poet Percy Bysshe Shelley.” Naturally. If Americans, as Gore Vidal says, are both Puritans and Romantics, then the Romance must begin in the South. Shelley is the South’s favorite poet; Southerners name their sons Shelley.

❡

Now if you’re a Yankee I can hear you grumbling, “Texas isn’t in the South; it’s in the Southwest, which is something else entirely.” Or more up-to-date Yankees will refer to the “Sunbelt” stretching from Florida around the Gulf to Houston and on west. I must confess I find these to be distinctions without differences. The Southwest was a fiction Lyndon Johnson invented when it became clear he would not win the South; the Sunbelt, where Nixon liked to say his cronies came from, is a cultural fiction, if an economic fact. Northerners choose to refigure the map, I suspect, because the revision places the energy and industrial wealth of Texas in exemplary contrast to the racism and supposed rural character of the “true” South. Puritans demand a moral and hold that riches reward virtue; they are discontent with the prospect of unreconstructed rednecks becoming the most prosperous element of the population.

But Texas is Southern in the good sense and the bad, and it can never be understood if it is seceded from the Confederacy. Take the racism. In small towns and among older people it persists unchanged. Among the Houston young, the racism may be disguised by lighthearted “nigger” jokes told on the understanding that, of course, we’re both liberals, we all know better—and isn’t it fun to say “nigger,” to use the real down-home word, the very word they use?

And so it might be if integration were more secure, equality more fully achieved, and the past more distant. As things stand, the jokes betray anxiety at best and conceal bigotry at worst.

Or take the rural character of Texas life. Although four out of five Texans live in cities, they are often from farms and dream of returning to them. The big, raw countryside—the fly-blown Nehi sign, the glass of ice tea on the porch swing in the sweltering evening heat, the shriveled grapes in the arbor in the back yard, the “bauking” of chickens, the rust-speckled blades of the creaking windmill, the trail of dust behind the pickup truck—this desolate countryside is both literally and spiritually close to the booming metropolises.

❡

“What are you doing here in Houston?” my friend asked. “Business?”

“No, just looking around.”

“You came here for fun? To Houston?”

Texans may be chauvinists, but few of them are loyal to Houston (though some transplanted Northerners defend it). It is only a place to run away to, a town where you can make a fast buck and then get out without regret—a sort of cloverleaf in the American Route to Riches.

My friend, sensing I was more chatty than randy and confident that I’d studied his text with care, hailed a waiter he knew and started giggling with him. Perhaps we’d understood each other too well to be mutually attracted. There were no occlusions in communication, those breaks in apprehension that awaken desire. Sex with strangers is an alternative to language, the code that replaces speech.

Inside the Locker things were picking up. It was midnight and the dance floor was crowded, as was the pool room. The prevailing “heavy” look for this malarial climate seems to be a black, sleeveless T-shirt, black or blue denims, and cowboy boots. Here and there, however, were ensembles that seemed ill-sorted. A tall, lanky man ambled past decked out in a ten-gallon hat, a faded workshirt, patched jeans—and sneakers. Home on the range in sneakers? Or the forty-year-old standing beside me wearing engineer boots, a black leather vest, chaps—and a cowboy hat. Yet another man had on an S-and-M top (chains, leather, tattoos)—and shorts.

These are expressions of individual taste in a state where personal flair is still regarded with nostalgic approval. By day, as one walks through the miles of air-conditioned corridors below the business district, one sees mostly fresh-faced executives in three-piece summer suits. But every once in a while one encounters an old, unbowed Buffalo Bill, his white locks flowing out from under his weathered Stetson, his $300 boots worn but polished, and a string tie around his neck—he is the magnate who grumbles about how the Yankees have turned Houston into a damn dude ranch.

Despite its architectural splendors and its hospitality to the arts, its influx of Northerners and its go-go economy (a survey revealed that young executives in Houston regarded a 10 percent annual raise as the minimum they would accept), the city remains raw. One talks to a tall twenty-year-old with an Adam’s apple that rises and falls obscenely along his taut neck. His voice is too loud, given the social distance, but it goes with the depthless eyes that seem focused on a distant figure. “My damn dad,” he drawls rapidly—that is a trick of the Texas accent, a Southern intonation speeded up—“tried to stop me going with guys. Ha! I beat that son of a bitch up. I slugged my goddamn brother, too, till he was a bloody pulp. My mom was screaming so I chased her around the house. See”—here he lowers his voice a bit—“I’d gotten this damn bitch I knew in high school pregnant, so the old man was hollering about that, too. But I’m bigger than him, I’ll knock out his fuckin’ teeth. I told the bitch to get her cunt scraped—then I moved in with Joey.” He told me more—of night rides in old cars with six buddies hee-hawing and gulping down a carton of beer, of straight guys from high school he lured home and then fucked (using cooperative girls as bait), of parents howling around the house trying to shut down a late pot-and-disco party—but I withdrew from him. I didn’t want to hear any more. Sure, I like tough guys, but only if the toughness is undermined by warmth and experience, only if I sense that in this man’s head there is somewhere a court of higher appeal. I felt awed and overpowered—was this the gay liberation we had had in mind?—and headed home to my motel, at last to sleep.

This rawness crops up everywhere. Houston is a city where businessmen chew gum, sport long ginger sideburns and Baptist pins on their lapels, smoke cigars, dangle calculators from their belts, carry pens above their hearts in aqua plastic inserts, and choose beige summer suits with dark brown stitching to match their dark brown shirts underneath. It is the place where, during the fuel shortage in the North, a block-long Cadillac carried a bumper sticker that read, “Let Them Freeze In the Dark.”

It is also the town where I met Harv. He approached me at the big disco, Numbers, with an opening line so contrived it was winning: “I’m doing a survey for the New York Times. Do you like blonds? How do you feel about blue eyes? And how would you like the best blow job in Houston?” We never got to the blow-job stage, but we did have a couple of drinks together in the glassed-in booth upstairs. Downstairs, lights strafed the crowded floor and glowed behind white silk curtains billowing inside tall, fancy scrollwork frames (I was reminded of the decor of a 1920s movie palace). Harv was a computer expert; he had been working late all week unscrambling a lousy program written by someone else. The pride he took in his work was all the greater because he was a self-made man. He had always fought with his parents, he told me—dark, murderous fights—and they fought with each other. When he was eight he begged them to send him away to boarding school. They complied, but when he came home for holidays he found them even more intolerable. The old hostility flared up again. After a particularly tormented, tormenting session his parents kicked him out. He was fourteen and had only $3 to his name. He worked in stores around his little Texas town until he finished high school. He then joined the Navy and was assigned a job in intelligence. At night he took more and more courses, determined to make something of himself—until one night, during a calculus exam, the numbers swam before his eyes and he could not read the questions. He had been, he told me, “overcome by nervous exhaustion.”

After the Navy, Harv obtained a position in Houston with a computer-programming firm and rose rapidly. Now he was just twenty-four and owned a 1972 Oldsmobile and a two-bedroom suburban house complete with a game room—and a wet bar and fireplace he had installed himself. Harv assured me this was just the beginning; his goal was to make $200 million. His taste in men was correspondingly ambitious: his first lover had won a major muscle-building contest. The only problem was the lover’s laziness. He was thirty-one and refused to work. “I did everything for him. I moved his mother into my house and took care of her. I bought him a new car and kept the old one for myself. But he kept pushing me. He didn’t come home for four days, so I went after him. I entered that bar and ordered him out. He said, ‘I ain’t going.’ I cleared the bar right out. I hit him, I ripped his shirt off, I lifted him by the seat of his pants and hauled him out. Then I asked him, ‘You wanna come home or you wanna go back in the bar?’ He said, ‘The bar, but I’m too bloody.’ So I said, ‘Well, I’ll drive you home and you can change and drive your car back, ’cause I don’t want to fool with you no more.’ I got him and the old lady out of my house. Now I live alone.”

I’ve omitted to say that Harv is a boxer and presses three hundred pounds but is short and baby-faced and sprays his hair and drenches himself in cologne. We necked for a while and he was soft, yielding. I had the impression of being in the plush grip of a powerful androgyne; beneath the hairless skin lethal muscles lay coiled. On the dance floor four guys were passing poppers, stomping fast and hard, and ripping out rebel yells. Given the heat, the humidity, the darkness outside, the feeble porchlights streaked with worrying mosquitoes, the disco seemed all the more improbable, an overnight Klondike improvisation. If the electricity being piped in were to fail, the lights would dim and cease their arbitrary but assured revolutions, the air would warm and thicken, the tape would grumble into silence—and we would be left in a hot tin shack somewhere in the middle of the bayous.

❡

The gaudy stereotype of American machismo is the Texas cowboy, but a visit to a gay cowboy bar forces one to recut that worn old plate and to print from it in fainter, more somber inks. The Brasos River Bottom is on a quiet side street but looks out toward the glowing spires of the business district. Inside are well-mannered couples sitting around the bar. A few people are playing pool. Most of the men are in their forties or fifties. A jukebox plays sad country-and-Western tunes while cowboys dance cheek to cheek. They sway to the strains of “Waltzing Across Texas” or do the two-step, or they perform a brisk foxtrot to an upbeat song like “Big Ball’s in Cowtown Tonight” (the title always draws a smile). Over the polished wood floor hangs a sign, “Get Hot or Get Out.” That is the only modern note, though the redneck belligerence neutralizes the up-to-date vocabulary.

The etiquette is formal, almost severe. A brief nod of the head has taken the place of the dance-class bow from the waist. If both men are the same height, one of them (usually the one who leads) removes his 10VRanch cowboy hat and holds it in his hand behind his partner’s back. Since it is summer most of the hats are straw. The shirts, however, are long-sleeved; cowboys are frugal people who wear the same clothes year in and year out. As the men danced to the impassioned strains of Tammy Wynette singing Johnny Paycheck’s “You Hurt the Love Right Out of Me,” their faces were unsmiling. I was reminded of a story an Argentine once told me of a tango contest on the pampas: as the gauchos glided back and forth to heartbreaking lyrics about jealousy, great tears streamed down their stoic faces. It was the same here, except the words also covered divorce and the Pill.

When a city slicker has a jerk-off fantasy about cowboys, he usually forgets their true distinguishing marks—the air of detachment and the polite, old-fashioned decorum. He ignores the fact that cowboys are low in perceived status, suspicious of outsiders, grave, insecure, a bit touching—and quite conventional sex (they would be appalled by rough stuff, for instance). At the Brasos River Bottom, smoking grass (so common in all the other Houston bars) is forbidden, as is pissing in the patio (a curt sign reads, “Rest Rooms Are Inside”). The spirit that reigns is respectable and cozy—a few old friends getting together for a beer.

Only about half of the customers are genuine cowboys or farm people; they are the ones most reluctant to discuss their origins and work, as though they are afraid you might laugh at them. But for all Texans the emergence of the Western look has come as a relief. Ten years ago most Texans were uncomfortable in their alligator shirts, chinos, and Topsiders; now they have received permission to slip back into the clothes they wore as teenagers.

For most Northerners, Texas is the home of the real men. The cowboys, the rednecks, the outspoken self-made right-wing millionaires strike us as either the best or worst examples of American manliness. The metal-drilling voice; the flashes of canniness and dry humor; the loping walk and the rangy gestures; the readiness to offer help and the reluctance to accept it; the unspoken code of personal honor; the physical courage and the unexpected grace in combat—all these are aspects of the Man, and for most of us He is a Texan.

This is, obviously, the movie version, but it is based on fact. The ideal is not an illusion, nor is it contemptible, no matter what damage it may have done. Many people who scorn it in conversation want to submit to it in bed. Those who believe machismo reeks of violence choose to forget that it once stood for honor as well. Until recently, as a Houston lawyer told me, Texas businessmen could conclude staggering transactions with just a handshake. Today, the invasion of Yankees has meant that all deals must be firmed up with written contracts. The gentleman might have been more tough than gentle, but he was at least honest.

Nor are courage, strength, a touchy pride, and a muted range of emotions without their usefulness. They are the traits of the pioneer, quick to defend what he has won and slow to complain about what he has lost. Nor is the frontier a mythical past in Texas. Both my parents are Texans and most of my relatives still live there. My paternal grandfather came to Texas from Louisiana in a covered wagon. My maternal grandmother’s parents were homesteaders, and my mother remembers vividly her girlhood on that farm with its smokehouse, its cool dugout under the pump house, its pecan trees along the creek, its rooms tacked onto the original cabin, its tribe of twelve uncles and aunts ruled by a mother who presided from an oak rocker where she read the Bible, chewed tobacco, and concocted herbal cures. Her husband was silent, hardworking, and strong.

When my mother returned to her home town for a reunion a few years ago and stepped breezily out of her Cadillac, an ancient woman wearing a bonnet approached her and asked her name. The name was given and the woman said, “Then I am the first person who kissed you. I was the midwife. As soon as you were born, I said to your mother, ‘I’m going to kiss her.’ Your mother said, ‘Don’t kiss that nasty old thing till you’ve washed her,’ but I didn’t wait. I was afraid someone would beat me to it.” My mother is seventy-five; the midwife must be in her nineties.

I mention all this only to remind the reader that the day of early settlers is within living memory for Texans and that the frontier ideal of manliness was until recently functional, needed. My own father worked as a cowboy when he was young, before he moved North and became a businessman. My childhood was a battlefield on which two opposing Texas forces fought it out—the strictures of manliness and the aspirations toward culture. My parents divorced when I was seven, and I was shunted back and forth between them. What my mother wanted me to be was artistic, creative, someone who “contributed” to society; her father had been a math prof in a rural junior college and she herself had taught grade school. (Texas has always spent large sums on education. The school teacher remains the beacon of culture; and many a modest home has a good library of the classics, headed by the Harvard Five-foot Shelf. Even today a dedication to culture is maintained in Texas; after all, Houston is the only American city aside from New York to have a full complement of resident opera, ballet, theater, and symphony. No matter that old oilmen snore through a Handel revival; they have at least done their bit for uplift.)

My father subscribed to my mother’s values in passing, though they struck him as more appropriate to a girl than a growing boy. What he wanted in a son was someone brave, quiet, hardworking, unemotional, modest. I can remember traveling to Mexico with him once after I’d spent a year with my mother. I embarrassed him by being a know-it-all and by admiring the cathedrals with too much enthusiasm. He drew me aside and said, “A man doesn’t say ‘I love that building,’ he says ‘I like it.’ Don’t talk with your hands. And you shouldn’t correct older people, but if you must, say ‘In my opinion’ or ‘I believe’ or ‘I may be wrong, but I’ve heard...’ He also told me that I should never wear a wristwatch, smoke cigarettes, or use cologne—all sissy things. Men have pocket watches, smoke cigars, and use witch hazel. These are principles, alas, that I have failed to observe.

❡

I’ve talked with many Texas men about the way machismo was instilled in them, and they all agree it was done indirectly. I’ve never heard one male Texan say of another, “He’s a real man” or “He’s not very masculine” or anything of the sort, though I have heard a few women say of a child such things as “You’ll like him. He’s all boy.” (Usually the comment is repeated: “All boy.”) But manliness is never mentioned by men in Texas. I suppose the subject is too momentous and too tender to be voiced. What is talked about is sissiness. The shape of the unspoken province of manliness can easily be inferred from the explicit, exact, and surrounding contours of sissiness, much as Canada might be deduced as a potent shadow from the glittering boundaries of Alaska and our northern border.

If there were only two choices facing Texas WASPs—manliness or sissiness—then most of them would resemble the Chicanos, who are usually either fiercely butch or extravagantly nelly. But there is a third option available to white, middle-class men in Texas: the good school citizen. He cannot talk in a high voice or love the arts (though he may like them), lest he descend into sissiness. But he need not play contact sports or drink or brawl in order to ascend into manliness. The good school citizen can run for the student council, earn excellent grades, do charitable work, and lead his church group. He may date an equally serious, upright girl and “respect” her virginity. This option is the one most of the gay men I met in Texas took as teenagers. They may have experienced themselves as sissies, but they were not taken as such by their friends and neighbors.

There’s one last thing that should be said on this subject—the extraordinary naivete among rural people about homosexuality, at least in years gone by. Today television talk shows and the antics of Anita Bryant have made the word gay part of everyone’s vocabulary, but when I was a boy, I never heard homosexuality mentioned once. When I was twelve, my mother, sister, and I visited my grandparents in the village where they lived, formerly “the oil capital of the world” (as a tattered banner over the main street proclaimed) but by then virtually a ghost town (the wells had run dry). My grandmother let me bunk with my grandfather and he and I made passionate, nonstop love all night. So far so good, but in the morning I heard him in the living room telling the others, “That Eddie is such a sweet boy, we just hugged and kissed all night long.” My grandmother cooed with affection, “Well, isn’t he the sweetest thang,” but my mother and sister subsided into ominous silence. I slid out of bed and turned on the gas burner in the corner without lighting it; it was one of those free-standing grills, blue flames reddening bone-colored asbestos, fed by a hose out of the floor. Though I intended to kill myself, I chickened out, turned off the tap, and at last crept sheepishly into the living room. My mother was clearly alarmed, my sister derisive, but my grandparents beamed at me with all the charity of their innocent hearts. So gay love must have been in the nineteenth century. Other Texas boys have told me their own tales of gay idylls on farms and in small towns where general ignorance assured them personal immunity. I do not want to romanticize rural life, nor do I long for a return to Arcadia. I am simply suggesting that in the old Texas what could not be named was unknowingly tolerated—a far cry from the half-informed but well-indoctrinated Baptist bigotry of today.

The young man who took me to the Brasos River Bottom fell into the category of the good school citizen. He was not a cowboy, though he felt more comfortable there than in the other bars and had even, for a while, lived next door to it. He grew up in a small town in Oklahoma as one of three children out of four who eventually became gay (the others are a grown sister now in Austin and a teenage brother—a whiz at macrame—still at home with his folks). An older, straight sister lives in Houston but doesn’t see Bill because she’s “hurt” that he’s homosexual. His parents know about their children’s sexual orientation, but the gay kids dare not say too much to their mother because she too becomes “hurt.” The word reminded me of the way some Southern women control their families by displaying a conspicuous wound—the wound of pouting, of a long face and swollen eyes, of meals eaten in silence and dishes washed in martyred solitude, of unusual afternoon naps taken restlessly behind a half-closed door to the tune of resigned sighs. This is the mother who tells her gay son, “I don’t care what folks say about me, but it breaks my heart that they should laugh at you.”

As an adolescent Bill weighed a mirthful 230 pounds (he loved eating and didn’t mind the consequences). He was proficient on the tuba, the trumpet, the piano, and the organ; his parents even bought him an organ. As he explains without a trace of irony, “My older sister wanted an organ, too, but she was too skeered to ask for one. Me? I just upped and asked and got me a big old organ.”

True enough.

During grade school and high school Bill saved $10 a month for college (he was guided to this goal by an aunt who taught in Denton, Texas). As an undergraduate he slimmed down to 160 pounds by eating nothing but tuna and swimming daily. He became so talented in the water that he was asked to join the swim team. He gained local renown by singing show tunes in a silvery falsetto voice. After graduation he moved to Houston and became—well, I don’t want to reveal his identity, so I’ll say a repairman of expensive European equipment. He likes this blue-collar work that brings him into contact with the carriage trade and earns him a handsome salary. His friends, however, regard him as “unsettled”—a polite way of saying “low-class.”

I met Bill at an interesting moment in his life. He is just twenty-two, blond, handsome, and naturally trusting, though newly skeptical about other men’s interest in him (“I know I’m good-looking and don’t want to be liked just for that. Everyone is after me”). His attachment to the cowboy bar and the repair shop keeps him within a safe, small-town milieu. Yet that familiar circle is evaporating around him, a mist burning off to reveal larger but more perilous vistas. He dreams of knowing educated and civilized people and hopes he may find them in Texas but suspects they all live in the Northeast. He has just abandoned his old apartment, two rooms in a frame house where he kept comfortable family furniture and surrounded himself with images of his totemic animal, the tiger—tigers painted on black velvet, photos of tigers, stuffed toy tigers. His new place is in the Heights, the only hilly residential district of Houston, an area of big trees and houses that have porches, back doors, even attics. Here someone gay might buy his first house before moving on to a more modern and costly neighborhood.

Bill has purchased his house with an older friend, Chuck, a native of Houston (that rare species). It is a nice, slightly run-down place built in 1915, which they are restoring and improving. They’ve already installed central air conditioning and assembled one of those kitchens that foreigners and New Yorkers first envy and then laugh at (a cause-and-effect relationship). Wood cabinets, reaching all the way up to the twelve-foot ceiling, fill in the spaces left vacant by the microwave oven, the electric range, the dishwasher, the washing machine, and the garbage compactor. On one high shelf sit antique toy cars—a crude Dusenberg in painted balsa wood and a Hudson in gilded tin. Concealing the toaster in her skirts is an Aunt Jemima doll. In the window hangs an etched-glass reproduction of a Mucha poster of Bernhardt. No wonder Bill left his tigers on velvet behind; he is being inducted into the new art of Art Nouveau and camp memorabilia.

The living room is less resolutely up to date. Though an impressively thick Houston house-and-garden magazine lies open on a chair, the decor here has not yet emulated those coordinated pastels, those careless conversational islands stranded in a sea of beige carpet under an abstract, palette-knife daub. No, in this room the presence of the old Texas can be detected in the facing, matched couches covered in brown gingham, each paired with its own symmetrically placed mahogany coffee table, a place for dull visits from company rather than animated little chats. Inside a covered glass dish, tinted a delicate pink, rises a mound of miniature Tootsie Rolls and foil-wrapped candy kisses; one pictures relatives passing the dish around while discussing the route they took and the mileage they got.

❡

The curtains are drawn and the Venetian blinds tilted to screen out the afternoon glare. Here devolves that tedious Southern ritual called “visiting” (as in “Don’t do the dishes right now; sit down and we’ll visit for an hour”). Visiting is a long, ambling account of the births, marriages, and deaths of every person ever known by anyone, especially kin, no matter how remote.

Chuck tells me that he runs his own business, a pesticide service. For $100 a client’s house is sprayed four times a year. He needs to work only five hours a day; afternoons he devotes to soap operas on television. He is enthralled by one program and proudly tells me he once met two of its stars when they visited Houston to perform in a dinner theater. He longs to travel to New York in order to see the studio where the show is taped.

He explained to me the gay social life of Houston. “The men in the A group are well-to-do, over thirty-five, and very exclusive. They have lots of parties. You have to remember that Houston is a big party town. We party long and hard. Last year the A group had the Mother’s Party—everyone who dared brought his mom, so there were just hundreds of gay men and these nice old ladies. It was supposedly a great success. I wasn’t there. I’m not a socialite. They also had the Bicycle Party. About six hundred men rode from house to house on their bikes, and at each place they were given drinks and joints. It went on all Saturday until everyone fell off his bike. Or so I’ve heard tell. Now, the other group—”

“The B group?”

“No, we’ve got A’s but no B’s. The other group, which is younger, puts on the Miss Camp America contest to coincide with the real pageant in Atlantic City. It’s held in a hotel ballroom and more than a thousand guests attend. Each of the ten finalists displays his talent and presents himself in swimsuit and gown. I was Miss Hawaii, but they ruled me out for smoking my grass skirt.” He pauses; only a second too late do I realize I’ve been told a joke. “When the contestants are presented, they’re introduced with a dish.”

“A what?”

“A dish. You know, an embarrassing story about something they did during the last year. Like: on the big cookout your steaks weren’t rare; or on the freeway last October you got an attack of diarrhea all over yourself; or you’re known to have sucked a nigger dick—no, they wouldn’t say that, since blacks are present. They’d refer to dark meat or something.”

Lavish entertainments do comprise a large part of Houston gay life. Members of the A group throw patio parties for more than a hundred men and decorate the grounds with cabanas and parachutes stretched from the trees. Last spring’s big event was the “Mardi Gras Madness.” During the holiday invitations were handed out in New Orleans to attractive strangers; as they passed back through Houston on their way home, about a thousand congregated for the party. Houstonians stand in friendly opposition to Dallas. Whereas Dallas is characterized as snobbish, pissy, phony elegant, and uptight, Houston sees itself as down-to-earth, butch, rowdy, and egalitarian. The rivalry is amiable, and gay men from the one city are perpetually racing to the other to attend parties. In Houston jeans, crew cuts, and S and M are in vogue; in Dallas designer slacks, styled coiffures, and social climbing rather than lovemaking are preferred... or so the Houstonians would have it.

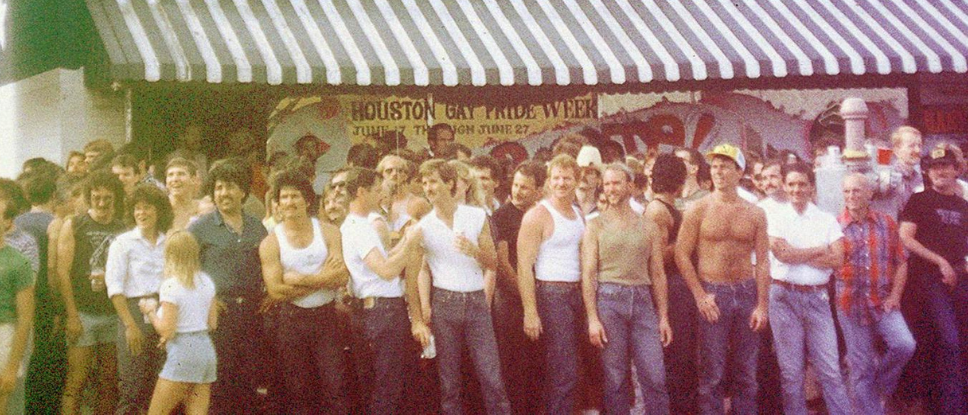

Chuck mentioned to me that he was interested in gay liberation but was unaware of anyone active in it. He was grateful when I passed on the phone number of someone I was planning to visit next. This young man, the perfect school citizen, was one of the organizers of Houston Town Meeting I, held in the Astroarena in May and June [1978]. The meeting, an open forum at which all members of the homosexual community could vote on major resolutions, was the first grass-roots political event for gays in the country. Despite the fact that homosexuals in Houston tend to be socially conservative, the meeting attracted some thirty-five hundred women and men. It provided Houston gays with a badly needed sense of community. There is no gay center. Until now the Wilde ’n’ Stein bookshop and the Unitarian Church have functioned as the only meeting places aside from bars.

The forum covered such topics as religion, mental health, the police, and the military. Before the meeting the Houston papers and television stations had ignored gay rights altogether, but the forum generated two front-page stories and several talk-show discussions. One of the newspaper stories concerned the attempt of the Harris County Commissioners Court to refuse the use of the Astroarena to a gay organization. In the article, one commissioner expressed his fear that a “nudist colony” would be asking for the arena next; another official, a Methodist, said, “My religious beliefs don’t go along with this.” The remaining three commissioners, who decided in favor of the gays, were equally squeamish, but their libertarianism overcame their distaste. One of them said, “As a conservative and advocate of limited government, I feel the constitutional protection of free speech must always take precedence over personal opinions of government officials.”

The chairperson of the meeting was Ginny Apuzzo, a professor at Brooklyn College and leader of the Gay Rights National Lobby; the keynote speaker was Sissy Farenthold, a Texas feminist and political reformer. Forty-two Texas gay organizations were present. One of these was an engineers’ group that has about a hundred members. As one of them told me, “You’d never believe those fellows are gay. They talk about nothing but oil drilling, offshore rigs, and freight forwarding. I guess we’re deliberate, rational, macho. But we want to be freer.”

❡

Perhaps the biggest problem facing Houston gays is violence in the streets. The gay ghetto is Montrose (once pronounced “Mont Rose” but now said, Yankee-style, “Mon Trose”). In May and June alone there were three stabbings and eight beatings in Montrose. The victims were gay men and the muggers teenage Chicanos. The police ignore the danger; if they do respond to a call for help, they often arrest the gay victim on the charge of public intoxication, a vague measure that permits officers to harass anyone they choose to. The Town Meeting called for the formation of a citizens’ police assistance group to patrol Montrose. It also asked for a civilian police-review board.

Police brutality remains troublesome. Last year five policemen beat a Chicano named Joe Torres and drowned him in the Buffalo Bayou (two of the cops were convicted of a misdemeanor). Two years ago a gay bartender, Gary Wayne Stock, made an illegal left turn and was shot to death by a Houston policeman, who was cleared of blame. The cop claims that Stock refused to pull over and was gunned down during a high-speed chase. But only eight minutes elapsed between Stock’s departure from work and the moment he was killed. Since he was shot only a few blocks away from the bar, he could scarcely have been speeding. The court failed to subpoena any gay witnesses.

Police raids on bars and adult bookstores are a familiar part of Houston gay life. A year ago the cops raided the Locker and made sure TV cameramen were there to expose the identities of the arrested patrons. There used to be a back room at the Locker where customers had sex on a dark balcony; plainclothesmen infiltrated the crowd and picked up one person after another by whispering “You’re under arrest.” Last January the police entered the bar with guns drawn, turned off the jukebox, and ordered the customers to put their hands above their heads against the wall. A new mayor and a new police chief seem to be less hostile, but gays have no legal assurance against further harassment.

The Town Meeting also called for the repeal of Section 21:06 of the Texas penal code, the sodomy law. Finally, the meeting censured discrimination within the gay community. The formation of a gay Chicano organization was especially welcomed—in recognition of the pressures exerted on gay Chicanos by their straight compatriots.

When the Town Meeting is held next year, it will undoubtedly discuss the problems of housing and employment. As things stand, two men or two women usually cannot rent a one-bedroom apartment in Houston, and if someone takes an apartment on his or her own and then moves a lover in, both of them can be (and usually are) evicted. Since houses sell for about $80,000 in Montrose, most gays are forced to rent and are thus clearly victimized by this form of legal discrimination. As for job discrimination, four of the men who organized the Town Meeting were fired from their jobs because of their activism. One of the co-chairs of the meeting wrote his name simply as “X,” explaining that his “lifetime career would be imperiled by openly signing this decree.” When photos were taken at the Town Meeting, many of those attending panicked. The fuss was still going on a month later when I visited Houston. One gay group had gone so far as to steal the photos from the archives.

Oppressive as this situation sounds, Houston gays stand a real chance of gaining power within the Texas Democratic Party. In a city of newcomers, where there is no Italian vote or Jewish bloc or labor vote, where everyone is young, materialistic, and indifferent to politics, a hardworking gay organization could become a force, especially since gays are so highly concentrated in the Montrose district. Similarly, gays in Dallas are sending delegates to the Democratic state convention, where they almost passed a resolution against the sodomy law. If only more gays would vote....

Despite the emerging gay clout, Texas will probably soon be faced with a version of California’s Briggs initiative barring gays from teaching positions. An educator at Texas A&M, who fought to integrate the University of Texas in 1969, is now trying to ban gay student organizations from his new campus. He is working hand in hand with a conservative black state legislator from Dallas who wants gay organizations routed out of all state schools and will undoubtedly introduce a Briggs-type initiative. Few legislators want to vote on a civil-rights issue, much less vote against such rights, but if they’re forced to express a yea or a nay on an open roll call, they will surely vote against gays or abstain. Obviously Texas gays must organize even more vigorously than they have already.

❡

The young man I met who is high up in the Town Meeting and the Houston Gay Political Caucus is in his twenties and from what Texans would call a “fine family.” Prematurely balding, he has only a tuft of silky hair to indicate where his forehead once stopped. His dimples are so deep that in an overhead light his mouth appears to be a slim dash between thick parentheses. His eyebrows grow together but do not suggest jealousy, rather wistful earnestness. Yet when the phone rings this shy man sounds jocular, back-slapping—a good ole boy. It is a manner that works wonders with older Southern businessmen. Houston gays are lucky to have Tom (as I’ll call him) as a spokesman.

The story of his coming-out is a tribute to his tenacity. As early as the seventh grade he knew he was gay, but like many truly queer boys he did not engage in the normal homosexual romps of puberty. In high school in Louisiana he was the first-chair flutist and became friendly with the first-chair oboist, who was notorious as the school fag. Because of their friendship Tom was kept out of the prestigious junior Kiwanis Club, so he turned around and started an American Field Service Club (the school-citizen strategy initiated dangerously late in the day). This office catapulted him into the president’s council. His reputation as a homosexual, undeserved up to this point, continued to haunt him; anonymous teenage boys called him and threatened to reveal his queerness to his parents, and two guys in the band asked him outright for blow jobs. When Tom demurred, they started a whisper campaign against him.

The oboist had by this time discovered a gay bar. Tom went along one night. When someone asked him how long he’d been gay, he didn’t answer—he didn’t know what the word meant. The oboist was dating an older man. When the affair cooled off, the oboist hanged himself from a tree. The police grilled Tom for hours about a possible motive. Tom kept silent, but he was so upset he nailed the closet door shut. In college he majored in marketing, became an officer of his fraternity, and went to bed with women. But the cure didn’t take. One of his school friends was making gasoline money as a hustler. Tom went with him to a gay bar and ran into a fraternity brother who said, “It’s about time you came out, Miss Thing.”

Tom did come out—and immediately came down with hepatitis. When he returned to school his fraternity brothers began to harass him; they hounded him out of the house. When he told his parents he was gay, they were outraged. Rich and prominent in politics, his father said, “We don’t want to consort with your kind.” His sister, an admirer of Anita Bryant, dropped him. Ridiculed and disowned, Tom could do nothing but leave town. Like so many other gay Southerners, he was attracted to Houston, the Ithaca of so many adventurers.

College graduates like Tom go to Houston to find good jobs in industry; working-class teenage runaways become hustlers. Recently Houston TV ran a five-part program on hustlers that “embarrassed” the gay community. The program did ignore the efforts of gay organizations to help runaways. Nevertheless, I’m not convinced that embarrassment is appropriate. Houston is, after all, the site of the “Houston murders,” those grisly slayings of homeless youths. There is no use pretending the gay community is free of psychopaths. This problem must be dealt with openly and interpreted lucidly to the public. Considering the way in which oppression deforms us, the miracle is that more of us aren’t mad.

In Houston Tom has found independence and freedom. He has a good position with a corporation that knows about his activism and accepts it. He owns a small apartment building, a brick four-family structure on a pretty street, and he lives there himself. His participation in gay politics has turned him into a sane, steady man, the very sort of upstanding type his parents would embrace if they had sufficient wit to do so. Tom confirmed me in my belief that activism is not only valuable for the community but also essential for one’s own mental health. Being gay in a straight world, even in a hypothetically permissive straight world, is so alienating that the only way to avoid depression is through the assertion of one’s own gay identity. Anger can take three forms—self-hatred, uncontrollable rage, and calm but constant self-assertion. The first solution is tiresome, the second useless, the third wise; Tom has chosen wisely.

❡

Hank and Eddie, as I’ll call them, invited me to dinner one night. They live in a Montrose apartment complex that is 70 percent gay and subject to the usual Houston rapid turnover of tenants. Hank has been there longer than anyone else—three years. He is twenty-nine, a handsome Floridian who is as smooth as a public-relations man; he knows how to project his considerable charms, but quietly, quietly. Eddie is twenty-five but looks seventeen, a small, perfect, exquisitely made animal so endearing that the desire or envy he might awaken is instantly tranquilized into friendship for him—the only recourse for an admirer, since his beauty is the kind that would otherwise inspire frustration. He is lapis-eyed and wears his black hair slicked back in a d.a., a quaint “period” touch that lends poignancy to his slender neck and small head. His youthfulness embarrasses him and on the job he smokes cigarettes, drinks coffee, and wears a tie to appear older.

Eddie grew up in a small Texas town but is now quite the sophisticate. He works for a shipping broker (Houston is one of the country’s busiest ports), and most of the 250 people in his office know he is gay and accept it, even relish it. Women ask him to explain the fine points of fellatio, which he does; recently they’ve moved on to more serious questions about back rooms and fistfucking. They also feel free to pat him on the ass (“because I’m a man and gay,” he observes with a trace of irritation). He’s called the “token gay” to his face; that’s a standing joke. When Hank sends him flowers, Eddie can put them on his desk and everyone beams. What they can’t grasp, Eddie tells me, is that he’s not Hank’s “wife.” Any suggestion that their roles are reversible will puzzle, even vex his straight co-workers.

Just as the Saturnalia, that grotesque mirror of society, confirmed the Romans in their belief that the world was hierarchical and proved (through its temporary elevation of slaves to freemen) that slavery and freedom must be enduring categories, so the perpetuation of traditional masculine and feminine roles by homosexual couples serves to demonstrate the inevitability and “naturalness” of such roles. The only threat of anarchy that homosexuality poses is in its openness to new relationships immune from the ancient corruption of the subjugation of one partner by another. If Eddie is not Hank’s wife, then marriage itself is challenged and heterosexuals are no longer able to find in gay life fun-house distortions of their own unsatisfactory arrangements. I am not, mind you, opposed to gay role-playing; that would be impertinent and display an ignorance of our moment in history. I’m simply noticing that the new gay ethic, which pairs equals and attempts to dismiss jealousy and possessiveness as leftovers from an era when marriage was primarily an economic transaction rather than an affectional tie—that this new ethic distresses even well-disposed heterosexuals.

❡

When I arrived in Dallas it was suffering from the seventeenth straight day in the hundreds. It was, as Texans say, one of those days when chickens lay fried eggs. No rain had fallen for more than a month and the trees were turning brown. At night the temperature dropped only into the eighties. People were buying four-hundred-pound blocks of ice and dumping them into their swimming pools, with no appreciable effect. Everyone was pale; it was too hot to take the sun. Six people had died in the last week from heat prostration. The incidence of crimes of passion had increased, but the number of robberies had declined; it was too hot to go out and steal. The city was crazy with cabin fever.

The mood of Dallas also struck me as near the riot stage. Down the street from my hotel a crowd of Chicanos in the park was protesting the slaying of a twelve-year-old boy. The child had stolen eight dollars’ worth of goods. When he was arrested a cop interrogated him while playing Russian roulette with a pistol aimed at the boy’s head. This game resulted in the boy’s death—and a very short sentence for the officer, who was convicted only of involuntary manslaughter.

Dallas is surer of itself than Houston, more rigid and smug. Whereas Houston is a young town, Dallas is the usual gerontocracy. Dallas is richer than Houston (it has one thousand million-dollar companies, as opposed to Houston’s six hundred). Houston has new oil money, Dallas old banking wealth. In Houston gay circles, money counts for little and family for nothing; Dallas, by contrast, is status conscious.

Dallas is the design center of the Southwest, and I was pleased to spend an evening with a successful decorator. His tenth-floor apartment was in Turtle Creek, the most expensive gay neighborhood (Oaklawn is the less expensive ghetto). His apartment was decorated in taupes, browns, and grays and commanded a full view of the city. On one wall was a painting of the archangel Lucifer falling from heaven, a wing catching fire. On the facing wall hung an eventless Barbizon landscape, the thick gold frame alone certifying the significance of its frowsy pastoral inanities. There were bookcases, but they were filled with untouched matching sets with good bindings—“book furniture,” as they say in the trade, ordered by the yard. A copy of Donatello’s wicked David smiled in at me from the glassed-in balcony garden. The fur throws hurled everywhere would have seemed oppressive had one remembered the temperature, but one does not remember it in Texas. Just as Houston sells more sables in July than New York does in December, in the same way Dallas decorators ignore the climate, the terrain, and our century and concoct their fantasies of a polar Paris of the Belle Epoque and seal them in air-conditioned cubes.

Steve wore a white, short-sleeved Egyptian cotton shirt into which had been sewn blue panels. Around his neck dangled a silver bauble. His slacks were pocketless, revealing his trim figure; though he is in his mid-forties he still weighs just 145 pounds, lean for his height (five-foot-nine). Under his arm he carries a purse shaped like a dop kit. He drove us in his Cadillac to the Bronx, a restaurant for straights and gays with a friendly atmosphere. In Texas coffee is served throughout the meal. Over our first cup, Steve told me, “I’ve been wanting to have plastic surgery for some time now, but my daughter wouldn’t let me. She said, ‘People already think you’re my brother or boyfriend.’ We went on a Caribbean cruise together and folks did make that mistake. ‘Wait till I’m married,’ she said. Well, I just gave her away to a nice boy and now I’m going to have my eyes tightened, my nose thinned, my chin made stronger. The whole thing will cost only $3,000. I never get a chance to visit with my mother; she’ll come to Dallas and take care of me for two weeks while I recuperate. The doctor’s here in Dallas. I like his attitude. He considers a face-lift preventive and says the second and third operations are always easier. Some of my friends, I fear, waited too long.”

I ask him how he happens to have a daughter. “I’m from a town in the Panhandle,” he says. “My father was a deacon in the Baptist church, my wife’s father was a deacon, and I became a deacon. My wife and I met at a Baptist college, married young, and had a boy and a girl. Although I fooled around with guys, it never occurred to me that two men could love each other. We were married happily for ten years and then I met a handsome guy from California and fell for him. I told my wife the next day I wanted a divorce, but I never confided in her that I was gay.

“Her parents were astounded; we were considered the ideal couple. Her father hired a private eye to investigate me. The detective found out everything. My father-in-law confronted me with the dirt and invited me to pray for strength to overcome this terrible sin. I refused the offer. A week later he tempted me with a tremendous sum of money. When I rejected it, he said, “We’re going to ruin you, take every penny you’ve got. Boy, a year from now you’ll be in the gutter.” In court my wife demanded a million dollars, half of my net worth, but she asked for it in cash. I was given three years to come up with the money; to do so I had to sell my holdings at a big loss. My ex-wife has remarried, this time to a man whose first wife left him for another woman. Well, they have something in common.

“My lover and I bought a twelve-room Victorian house for the price of the lot, $30,000. We spent twice that fixing it up, of course.”

“You stayed in that same town?”

“Yes. For two years no one would speak to us, just whisper behind our backs. But we hung in there. One day, I’ve heard, four important ladies were playing bridge and one of them said, ‘You know what they are,’ and the grande dame of our town replied, ‘I don’t care. They’re the only interesting men in town and I’d sleep with either of them.’ Everybody laughed and had to agree. It was a very dull place. Eventually we joined a country club as a couple and were invited to all the parties.”

“Did you live in an entirely straight world?”

“Lord, no,” he said. “We’d have big weekend parties of fifty men or so. They’d drive in from Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, Austin. In the attic we’d set up an orgy room, twelve mattresses on the floor, and show fuck films. On the second floor people would get high and eat. On the ground floor they’d dance. Our maid would prepare several big meals in advance, but even so, it kept us busy—people wouldn’t drive all that way just for one night.

“My children would visit and they loved my friend as much as me. We never discussed our homosexuality with them. Then, when my daughter was going to college, her mother wanted her to attend Baylor, the Baptist school. My daughter refused and I backed her up. My wife was so furious she sent a letter to my daughter telling her everything about me in the ugliest terms. When my daughter phoned me, I said, ‘Well, it’s all true. I’m glad your mother wrote that. Maybe she’ll calm down now.’ We had a good laugh.”

“And are you still with your lover?” I asked.

“No,” he said. “He wouldn’t work. I set him up in several businesses, but they all failed. Finally he blamed me for his failures and left me. I’ve moved to Dallas and started a whole new life. It’s very exciting.”

“Are you still a Baptist?”

“I no longer go to church, but I still worship God. I just assume He will reward me for the good things I’ve done and ignore the bad.”

“The bad?”

“My homosexuality.”

❡

The odd thing was that two days later I met someone at the baths who was from the very same small town in the Panhandle, though he didn’t know Steve. Although he had been in Dallas for four years working as a clerk, he hadn’t made any friends. He was intensely shy; his cheeks were cicatrized by deep acne scars. His eyes were an eerie blue, so pale he appeared blind. He had a lovely body and whispered to me with a sad smile, “Why don’t you lick me all over?”

He hadn’t come out till he was twenty-seven. Before that, the great event of his life had taken place in high school. A football player had awakened a grand passion in him, but they didn’t know each other. In the fall my friend had prayed for the athlete to be in one of his classes and was intensely disappointed not to see him. “So I just wished him there. I knew that would work. I became calm and sure enough he came in the door. He’d decided to take Spanish after all. We didn’t speak, but after class he grabbed my arm, the same way he took his girlfriend’s, and steered me down the hall. Nobody laughed. When we got to the cafeteria, he went his way and I went mine. One other time he touched me. We were riding in a car to a church affair and he put his leg next to mine.”

Suddenly my friend looked at me with genuine fear. “Do you own this place?” he asked.

“No,” I said.

“Sure?”

“I’m certain.” I have no idea what he feared or why that idea popped into his head. He seemed a naive country boy, though he was thirty-three years old. I had the impression he had never talked about these things before.

He went on with his story. He had never had sex until, when he was twenty-seven, a married man at work went down on him. “I felt real bad and the next day I said to him, ‘Why’d you do that?’ (That comes out as ‘thigh-yat.’) ‘I don’t never want you doing that again.’”

My friend laughed. “Two days later I was horny. His wife had gone to work and he called me and asked me over for breakfast. When I got there, he was nekkid. He was prancing around nekkid and I said, ‘You look real comfortable.’ He stretched out and said, ‘Why don’t you get comfortable, too, if you want to.’ So I did and that went on for three years. He took care of me; I never did anything. He looked like Chad Everett on TV. Then he moved to Dallas and I visited him. His wife came downstairs and said, ‘Why don’t you go on up there and sleep with him?’ I said, ‘Heck, no. I can stay on this here couch,’ but she insisted. I guess he must have told her. But then he got religion and was saved and we broke up.”

“What religion?”

“Baptist.”

❡

The Baptists in Dallas, as elsewhere, are the storm troopers of the anti-gay offensive. The zealous, if not over scholarly, minister of the First Baptist Church in Dallas (the world’s largest, as Texans say) thunders against homosexuals regularly from his television pulpit. In interpreting a passage from the scriptures about who will not be admitted into heaven, the minister identified “effeminates” as lesbians and the “philanderers” as gay men. The rest of his sermon was on that level. As a teacher used to handing out grades, I couldn’t help feeling that this minister was himself the big D in Dallas.

Across the street from his church one finds the Baptist Book Store—the usual outlines for sermons, a section for teenage missionaries, and many tracts designed to prevent Baptists from lapsing into astrology, the occult, Buddhism, and Mormonism. Quite a few volumes were devoted to the “Biblical way to pray away pounds.” Others ranged from the folksy (Ain’t God Good?) to Colson’s and Magruder’s confessions, inspirational volumes (the tale of a famous star’s blue baby told from the blue baby’s point of view), and books for teens in their own language (“I hear where you’re coming from, Lord”). For those who find reading a nuisance, much of this literature has been transferred onto cassettes; there is a whole battery of tapes on how to save your marriage.

Glancing through a Baptist encyclopedia of psychiatric disorders, I found a long, seemingly confused entry on homosexuality. The genetic argument was rejected (you’re not born gay); I suppose the doctrine of free will would insist on that. The causes of homosexuality that were cited included faulty glands (aren’t they genetic?), a domineering mother, and a shadowy or overcompetitive father (such a mother and father have always struck me as sounding like Italians, and I wonder why so few Italian men turn out to be gay). Fear of women was listed as another possible cause, for which the cure is—no, not man-woman sex, but mixed group therapy. Lesbians were ignored altogether. The entry concluded by saying that many practicing heterosexual men have psychological profiles that indicate they should be gay. The reason they’re not is that they’ve heard the call to God. In repression lies salvation.

My cousin’s son is studying to become a minister at this very Baptist center. Two years ago I visited his family in West Texas. At first I resisted discussing religion, but then I joined in the debates. For these people religion is the only form of intellectuality. They rise at six in the morning in order to spend an hour alone with their Bibles before breakfast. They have examined every aspect of the scriptures, and my cousin’s son is learning Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic in order to plumb the Bible’s depths. Not only is religion an exciting intellectual sport, it also establishes decency within the family. (I think it might be hard for some of my readers to understand that for many households that are perilously close to alcoholism, shiftlessness, and violence, religion represents an opposing urge toward sobriety, industry, and order.) Finally, I became aware that in order to raise their four children and send them to college, the parents had to make big sacrifices, never larger than now, when inflation is squeezing out the middle class. Daily sacrifice requires a rigorous regime, and the Baptist church provides that discipline.

To understand the vehemence of Baptists one must recognize what they are fighting: the broken home; the drunk father; the philandering mother; the meals eaten alone standing in front of the refrigerator; the arbitrary beatings of wife and children; the straying of teenagers into truancy and drug addiction. What we must bear in mind is that what we gay people have been saying defiantly and polemically is in fact objectively true: the family doesn’t work, especially not in the United States, the only nation in the industrial world that has no guaranteed family income program. Since the United States is also one of the few advanced countries with no public health system and very little free higher education, these expenses must be borne by the parents. Having children in a city is economically useless, a drain rather than a benefit, and the advantages of raising a family today are only spiritual or conventional, never practical. Religion is a last attempt to keep the institution afloat. Nor are any alternatives to the family visible, not even literally.

When I was with my relatives, I flew above their town in a private plane; below me were nothing but family houses, one after another. I met not one person who was over twenty-five and single. There are no apartment buildings, no singles’ bars, no discos. For someone living there, it must seem that there are only good families and bad families. The good families all go to church, and religion indicates not only piety but also education and a commitment to decency. What can sexual freedom mean to such people? In a real sense they can’t afford it.

Southern Baptists dislike homosexuals because they perceive gay men (they seldom think about lesbians) as hedonistic, selfish, dissolute—the very qualities they observe in families that have gone to seed. Some of the animosity must also be envy. Self-sacrifice doesn’t come easily to anyone, nor does fidelity. If gays are seen as both rich and promiscuous, as capable of indulging their every whim as consumers and Don Juans, then they represent a temptation, an affront, which must be condemned. Moreover, the very perversity (as they see it) of homosexuality must seem like a first step toward abandoning all moral strictures; if someone can face the ridicule of being branded queer, then he is egregious—literally, “outside the flock.” He has broken the social contract.

❡

Of course, gay men and women don’t really give up the harmonic principles of their youth; they simply transpose them into a new key. That was made clear to me one evening I spent in Dallas with a group of young professionals—a lawyer, an architect, and an executive. One of them, brought up in the Church of Christ, had come out in college with his “little brother” in the fraternity. The lover was a local rock star, and between them they dominated campus life. In college in the late sixties he did not defend gays—he didn’t know anyone else who was gay—but in 1969 as a high officer in the student council he worked to integrate the school and ease blacks into fraternities. Today he is a bit closety on the job but busy in gay politics. He is an attractive, liberal, thoroughly decent man. One of the other two men had been a Methodist minister before he came out. He is in an awkward position, since he is a feeling person sensitive to the slightest sign of pain or unhappiness in someone else—and also the leader of the most snobbish gay clique in Dallas. Proust once observed that snobbishness is a deep but narrow vice that cannot be extirpated—but that need not infect the rest of the character. Ted, nevertheless, feels the strain between his universal compassion and his exclusive tastes. Naturally enough he denied that there were cliques in Dallas and would admit to nothing more definite than “overlapping circles.” Once that distinction was established, he proceeded to tell me about last spring’s Easter Bonnet Party (some men wore feathered hats larger than those seen at the Folies-Bergère), about camping weekends by a lake in Oklahoma where some people (“not our circle,” which is too butch and sensible) hung chandeliers in the trees above their tents and ate off silver service on damask, and about the big Texas-OK (Oklahoma) football weekend in October when gays swarm in the streets as though it were Mardi Gras and Dallas hosts throw open their doors to five hundred guests at a time. Servants, stereos, drugs, open bars…

It was easy to see how Ted had climbed to his social pinnacle. He had dark, almost Indian features, a solid white crescent of teeth worthy of a Wrigley’s ad, an imposing build, and the nervous attentiveness of the professional host who nods and grins through one conversation while devising a plan to rescue Henry from the bore in the corner. When he left, he kissed his friends and murmured, “Well, good night, Sugar Booger.” My mother would like him; wouldn’t yours? The energy these men would have injected in another, heterosexual life into church clubs and country clubs is now diverted into gay social life and politics.

After Ted left, we all discussed cliques and the differences between Northern and Southern manners. In the South a host introduces a newcomer to everyone and says the guest’s name at least twice to make sure it has sunk in; in the North the host, sprawled and stoned on the couch, might confer a chilly nod on a new arrival. In the South people have a distinct party style quite different from their tête-à-tête manner. At a party people joke and clown, keep it light, and seldom disagree. In the North people don’t know how to behave in groups. They isolate one other person and argue with him. In the South, touching signifies friendliness, nothing more; in the North, it is invariably a sexual innuendo. Northerners consider Southerners to be “phony”; Southerners think of Yankees as “rude.” These differences are so subtle and yet so divisive that a Texas university is offering a course for Yankees in how to get along with Texans.