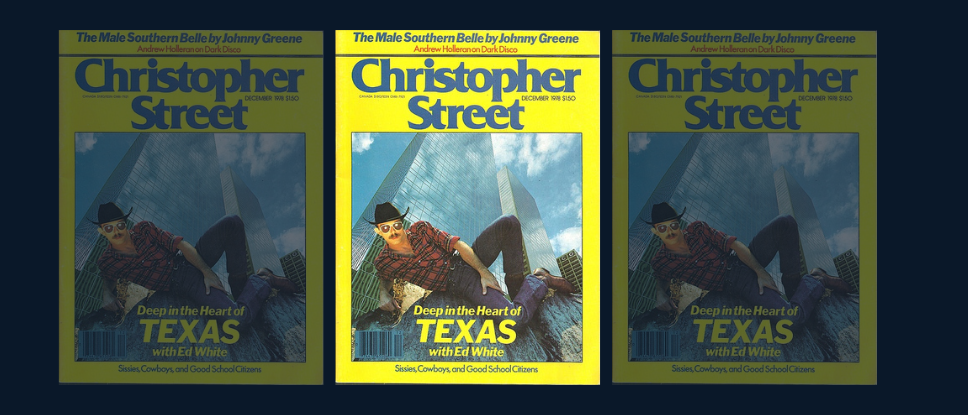

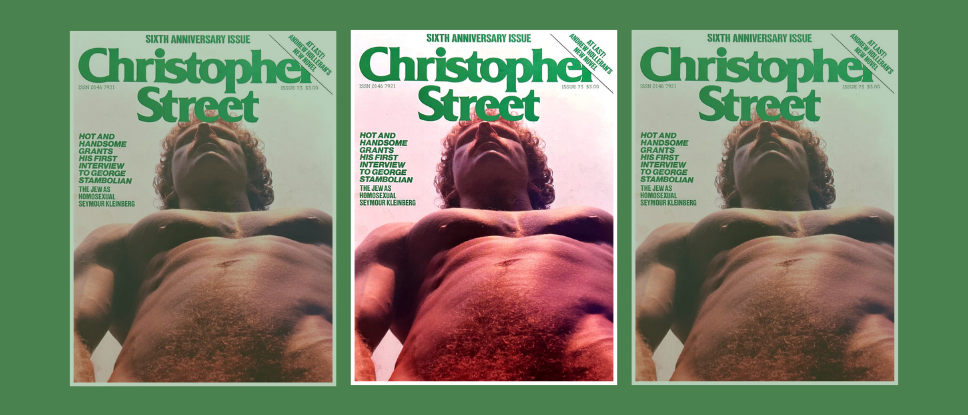

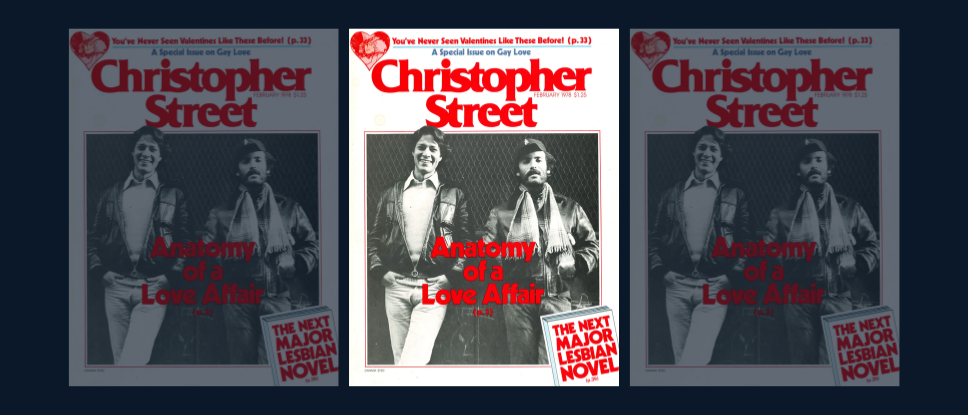

This article appeared in the December 1978 issue of Christopher Street.

There’s a new accessory in New York now: the large transistor radio cradled gracefully in one arm or hanging from a shoulder strap like a huge metallic communications purse. Like much fashion it started on the street and, as of this writing, is confined to adolescents of the Third World. They take their radios everywhere they go. If you love music, you may find yourself in the curious position of following a young man not because he is sexually interesting (or even sexually possible) but because the radio he carries is playing “Do or Die.”

This phenomenon may hit you in one of two ways: either you find the boy on the subway with his blaring radio inconsiderate or you applaud him for wishing to have music beside him every step he takes through life (and which of these two responses you feel often depends on whether you like the song or not).

And if you do like the song and he gets off at the wrong stop, no matter—chances are the radios on the street when you come up will be playing the same song, not to mention the stores on Eighth Street, which you can now traverse from Sixth Avenue to Astor Place without ever completely losing the strains of “Boogie Woogie Woogie,” if that’s what WKTU-FM is playing. WKTU-FM shocked us all one morning when we got up to turn on “The Mellow Sound” to get us through that first hazy hour of consciousness (John Denver, Cream of Wheat) and found it playing instead the song we had danced to the night before: sometime in the night it had become twenty-four-hour disco Muzak.

Well, all of this—the twenty-four-hour disco station, the radios carried down the street, the music played in shoe stores and gymnasiums—is a tribute to how far disco has come...or gone, if you feel that way about its rise from obscure dark rooms to the sunny sidewalk and the shag carpeting of The Athlete’s Foot in the Village.

But other things too have changed in that time. When I first came to New York, the radio station we listened to for the music that eventually became disco, WBLS, dispensed positive thinking to its ghetto audience; now that audience tends to drive Porsches. In those days, when you went out to dance, disco had no uniform sound. There was no one word to describe the variegated music we spent the night with. It was distinct enough for the discaire to begin a set quietly, build gradually to a climax, then let you down to start all over again. Do you remember that vanished custom? It happened three or four times a night if you stayed long enough, and you could follow the tantalizing process by which the discaire laid a solid foundation of slow songs and then subtly (if he was good, as they all seemed to be in those days) built you up to the catharsis, say, of Deodato’s “2001.” One thing for sure: disco was different then. The music was darker, sexual, troubled. Today the dark has vanished and the light is everywhere.

Two winters ago I walked into a discotheque and realized with a mixture of horror and disgust how far things had gone in this business. That was when I heard in the same night disco versions of “I Could Have Danced All Night” and (the mind reels) “The Little Drummer Boy.” Why didn’t the crowd stampede for the fire exits? Was I the only one who found these songs drivel? I went home that night in a terrible funk: I had seen the death of disco, I felt sure. That winter I let my membership in several clubs lapse and began asking everyone I knew, “What will we be doing after disco?” For I was certain that that form of diversion was kaput. The disco beat, which devotees of rock and jazz detest, suddenly seemed idiotic even to me, a certified disco maven.

A terrible uniformity of beat and style had come to dominate all disco music that year, so that when we went out we were never taken up, dropped, and taken up again several times in the course of a night. No, we entered the discotheque and stepped, as it were, on a moving jet of air that never slowed down until we ourselves stepped out of it—by simply leaving the room. Gloria Gaynor got faster with each song. By the time she did “How High the Moon” there was nothing left, said one acerbic friend, but the tarantella. Stepping onto the floor then was an occasion of apprehension, like gathering your energies to run the hundred-yard dash, for the music and the discaire playing it seemed part of a conspiracy to keep me hopping against my will. (What were we to do to “How High the Moon”? Use roller skates? Pogo sticks?) But by then disco was big business. What I used to think was as wonderful and mysterious as the dancing madness of the Middle Ages or the rites of Dionysus was now a page in the annual corporate report of Gulf & Western.

❡

There was nothing wrong with Gloria Gaynor, of course—there is nothing wrong with light disco. Some nights you arrive in tennis sneakers and your only regret is that you’re not allowed roller skates or a pogo stick. Some nights you do want to float very lightly. You’re feeling fast and cool and breezy, and light disco is just what you need. The wonderful lightness of “Spring Affair” (with its odd tinges of dark disco) is almost ethereal, and you rise and dip with it like a bird coasting on wind. But the dreck that falls in between, the Muzak of disco (which is clearly light), the fast, mechanical, monotonous, shallow stuff that is being produced for a mass market now, the kind of music one imagines hearing poolside at the Acapulco Hilton, beating against the brains of the guests as they squint into the sun looking for the pesky waiter who’s bringing them their Margaritas—that is light years away from the old dark disco, which did not know it was disco, which was simply a song played in a room where we gathered to dance.

Deep in a funk the night I decided disco was dead, I began to wonder about the songs we heard no more that, it seemed to me, had created another feeling altogether in those early days. But each time I named a song, I asked myself, Was that dark disco? If we were to buy that record and play it, would it really be different? Or was it the time and place and atmosphere, not the music at all? The songs I remembered vaguely, if at all, were not fast and sassy and full of androgynous choral effects. They were not—I was sure— invitations to visit Rio or disco versions of songs from My Fair Lady. They were songs you could dance to for a long time, because they concentrated energy rather than evaporated it, songs that went inside you, rather than lodging in your feet and joints the way light disco does. You hardly moved, but suddenly you were closer—slightly—to the person dancing with you, and you became conscious of your limbs, which even, as I remember, became heavier. You lowered your eyes. You closed them finally. It was gripping, real dancing, and the atmosphere in the room was one of surrender. Dark disco was our fado, our flamenco, our blues; it spoke of things in a voice partly melancholic, partly bemused by life, and wholly sexual. Dark disco was the song you sang to yourself on the first night of winter in New York walking down one of those long, dark, deserted blocks in Chelsea, when you realized anew that New York is also a winter city, a city where for one long season life turns indoors and we pursue freely our darker desires.

That was dark disco: late nights and love affairs and empty streets, and the sound of Al Green singing “Love and Happiness,” and the version of that song by First Choice. It was B.B. King at the Tenth Floor singing “To Know You Is to Love You.” It was the Masterpiece album of the Temptations, the sinister authority of those opening bars of “Papa Was a Rolling Stone,” or “In the Ghetto,” or the triumphant gloom of “Law of the Land.” It was, finally, a song whose singer I cannot even remember but which is played occasionally today and contains a line that goes: “So you grow up and start a family. ...” There was nothing strained or inconsequential about those songs. The last was even soft-spoken, exhausted, a song perhaps by a man on downs—not the downs we take as pills but rather the downs we take in life. It told me a little story (and how irrelevant to anything are the lyrics of light disco) of the whole sad progression of a life—the mundane pattern we all follow—but it told it in the most vulnerable mode, and we could all share it. We communed. The music wasn’t being done to us; it was being done with us. And that song, so casual, so low-key and easygoing, had in it ten times the power of the fastest show-stopper. It was sexual, bluesy, and what can only be called dark. It was not an invitation to fly away or a mad whirl about the room. Oh, give me a slow song any day, one as melancholy as “Love and Happiness,” which makes us dance from the pits of our stomachs (the solar plexus, if you will, where a French friend assures me all the major emotions are located) instead of the joints of our arms, the tips of our toes.

❡

A friend who knows this business far better than I do told me yesterday that there will always be dancers in this city—that they were there before disco and they’ll be there after disco. Still, wherever I go, I look for what comes next. The roller-skating disco in Flatbush? (The music now is so appropriate to roller-skating, the fast, monotonous, sexless disco that fills WKTU-FM.) Or will we abandon even that and just roller-skate through Central Park, as gay men are starting to do now on sunny weekends? Will we give dinner parties again? Stay home and form book clubs? When I arrived in New York, there were no back rooms and no discotheques; now there are many of each. In five years perhaps they will both have vanished, and we will have what in their place: Betamax societies? Will we all go to bed again at eleven, and do something in the morning? What? Not having been awake before noon in seven years myself, I am at a loss to say.

There is a solution, devotees of dance: dark disco still survives, in a curious way. It is this: To hear it once more, to enter that communion of the blood, don’t go out this Saturday night. Eat early, go to bed at ten and set your alarm for five; and then, having showered before you sleep, having chosen your T-shirt and jeans, get up with the bell and dress as quickly as any fireman going to a fire, hail a cab, and go down to the disco of your choice around five-thirty. You will pass the wondering faces of the dancers coming out—pale, white, sweaty, on their way home. You may have to hammer on the door to get the man lurking in the back to come forward and let you in. But do it. Pay your money and go upstairs and you will travel back in time to the days of dark disco. The place will have emptied slightly—depending on the quality of what has gone before—and you, fresh as the morning star, will step onto the floor and find a friend, and start to get the very best of the night. For the best disco is saved (who knows why) for last, as if, under this new regime, the old, dark disco is played covertly, in secret. Then you’ll hear “So you grow up and start a family,” and maybe “Love and Happiness” or whatever else does that to you. You’ll dance till seven, or eight, and when you come out you’ll have captured what you’ve missed for so many years now in this tyranny of light disco. Tap dancing went, and the cakewalk, too, and one day our disco will be as quaint as Glenn Miller. But could we not detain its evaporation a bit? That, at any rate, is my plea for dark disco. ❡