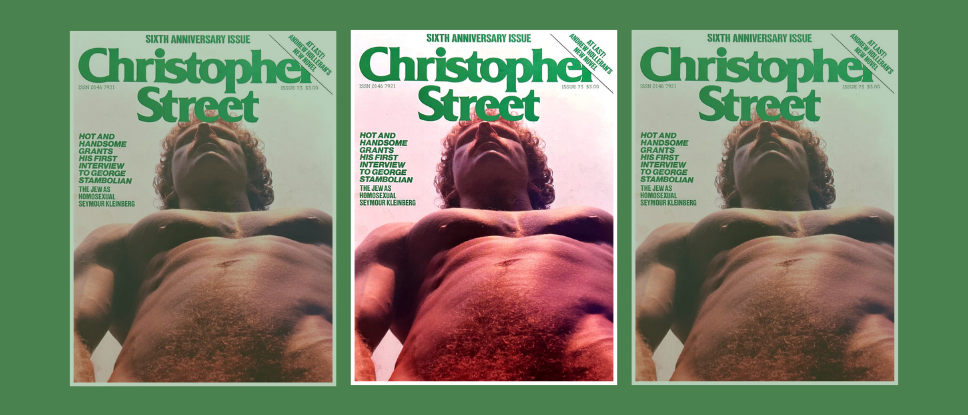

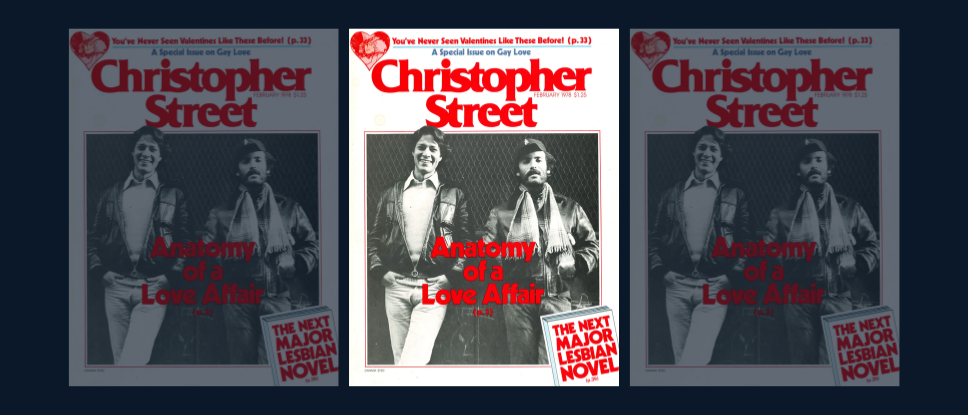

This article originally appeared in the February 1978 issue of Christopher Street on pages 3-16.

Previously in this series: Michael Denneny's introduction to "Anatomy of a Love Affair."

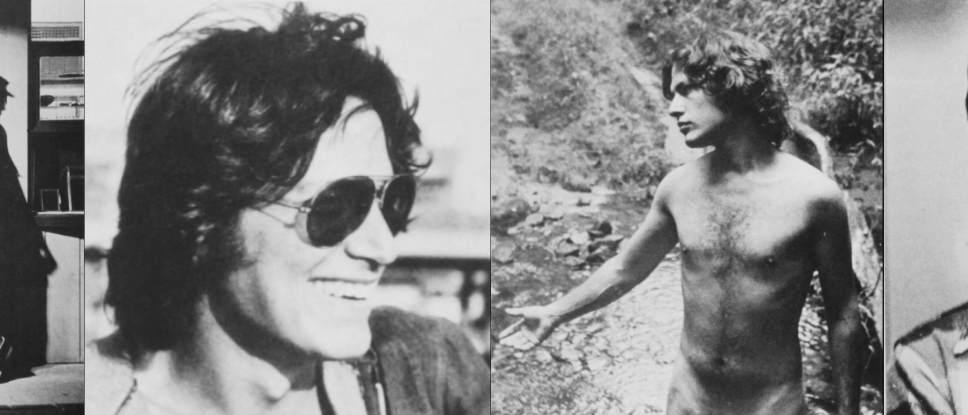

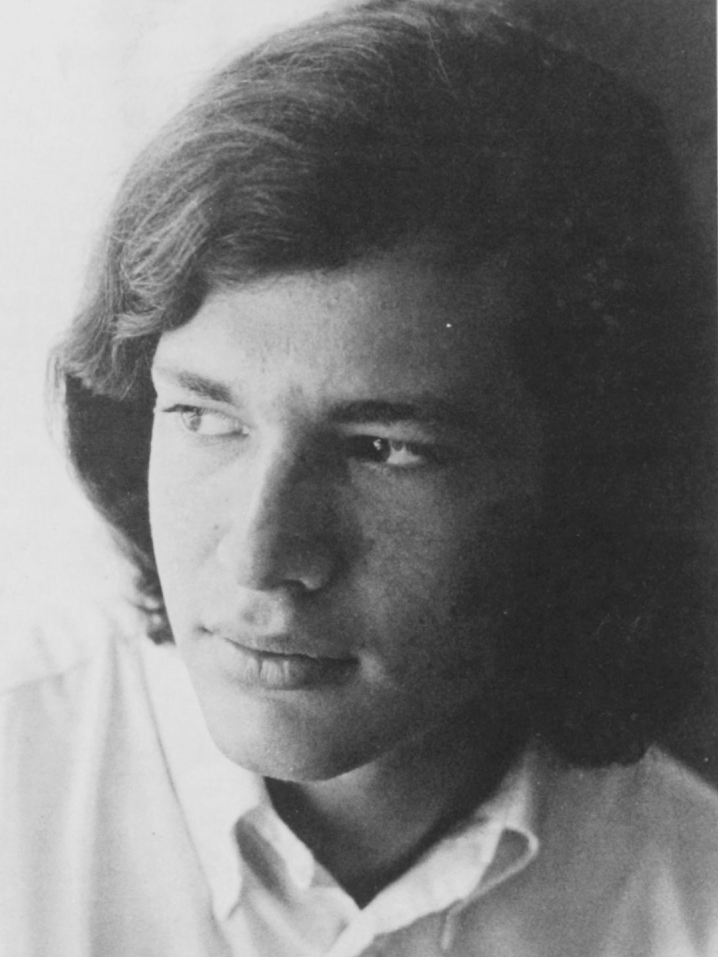

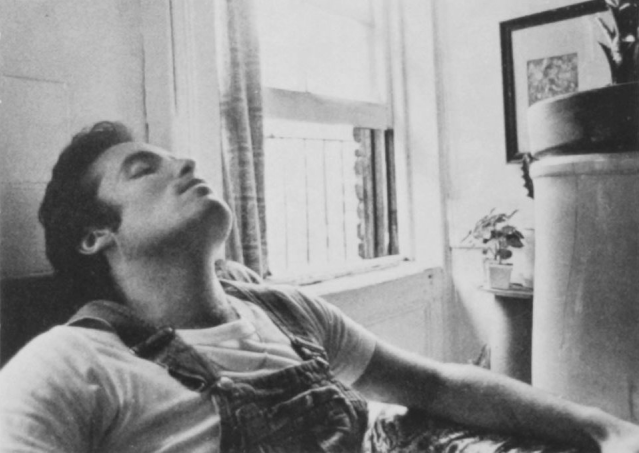

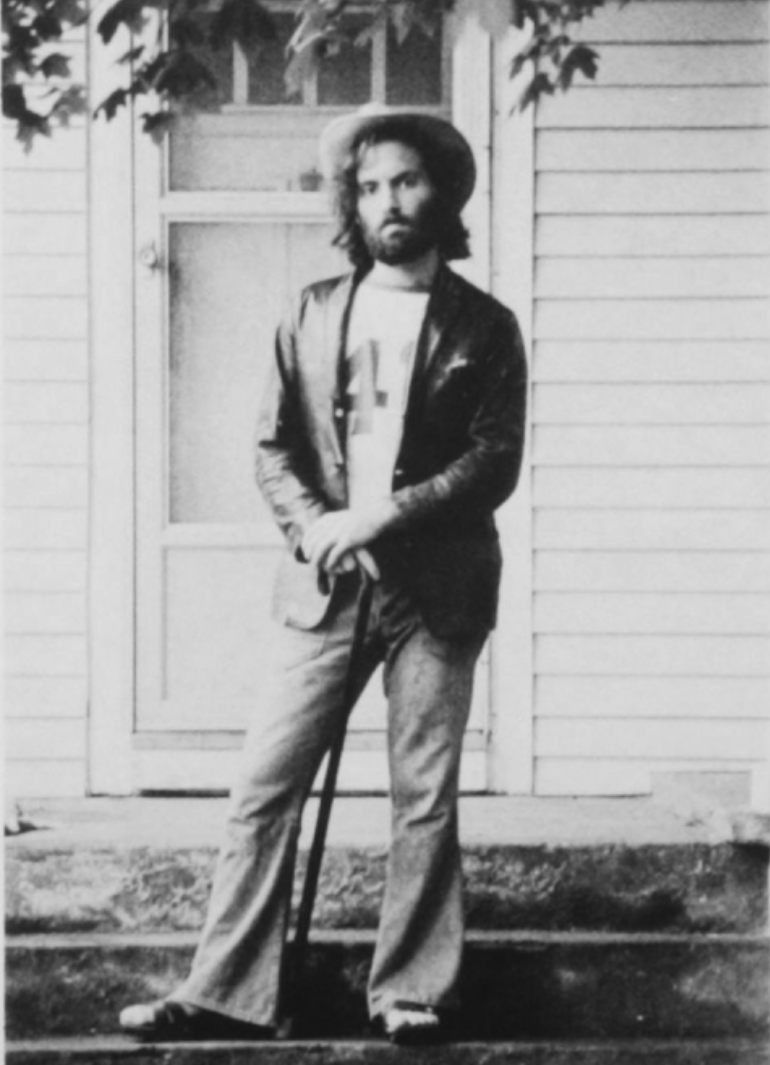

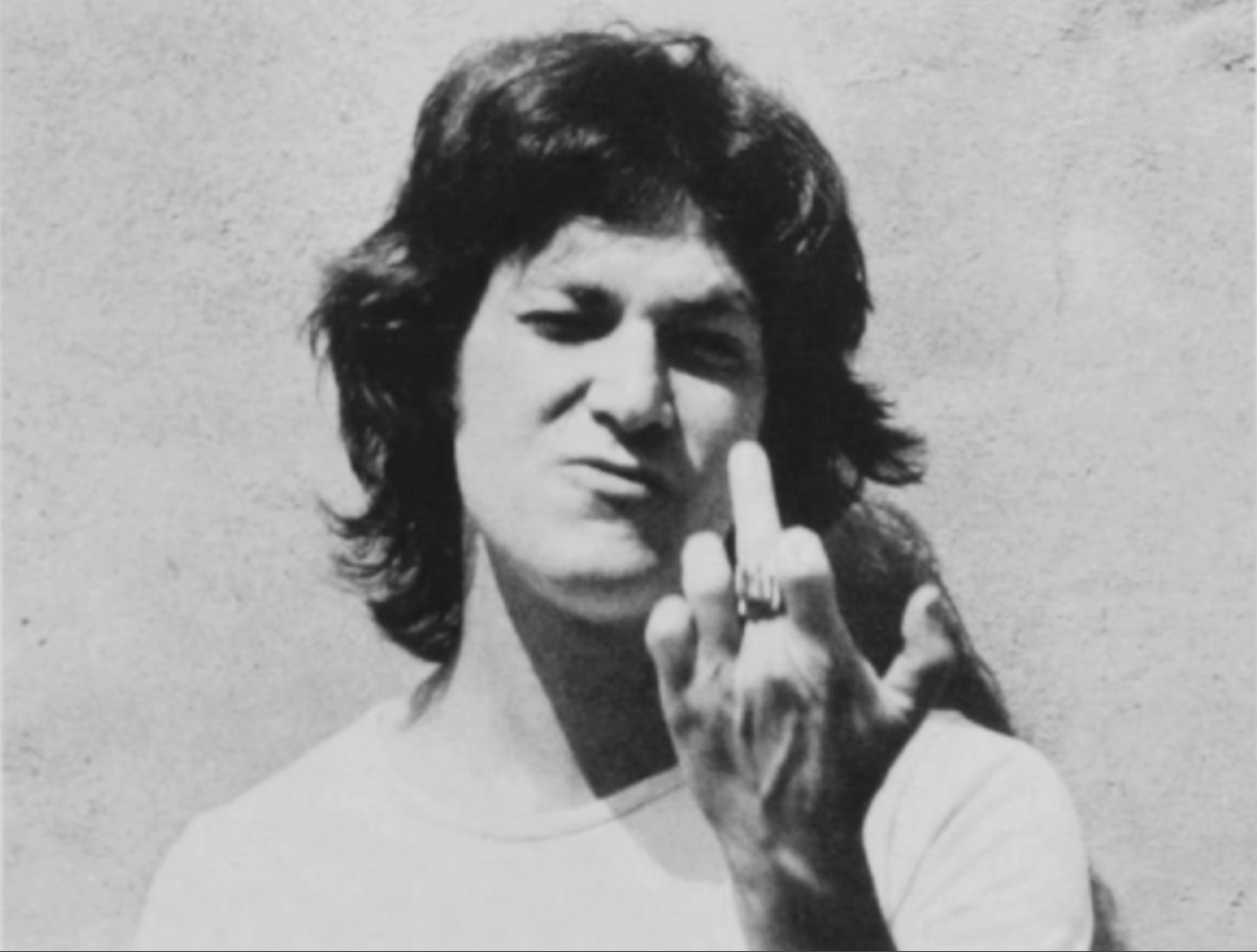

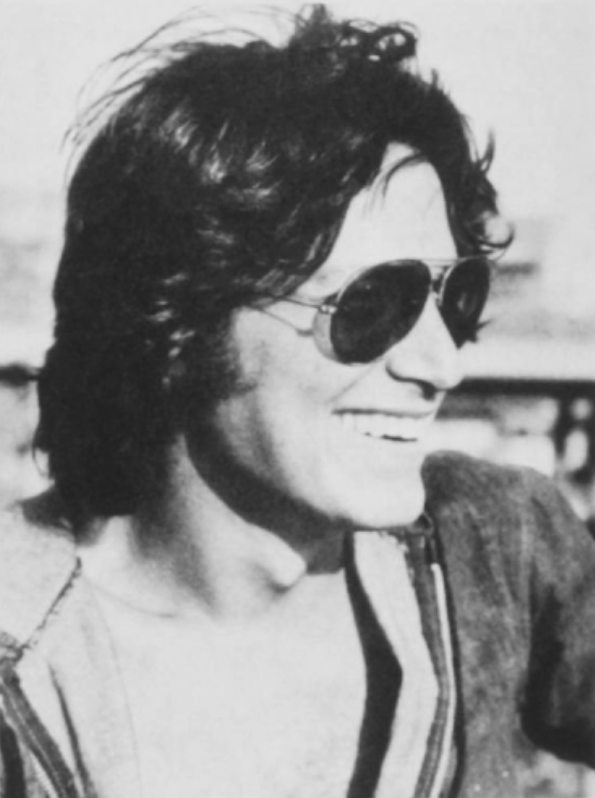

PHILIP GEFTER: Okay, this is photograph 1. I guess at this point I had just come out, although I’d already slept with a lot of men. I’d just gotten my hair cut and adopted a certain “gay” look, or what I recognized as a gay look, at that time. This is 1973.

MICHAEL DENNENY: How old were you?

I was twenty-one; I was cherubic. Neil, when he met me—and this is what I looked like—thought I was the quintessential innocent youth. That was his impression of me. Like Tadzio in Death in Venice, in fact—that’s the image he had.

Is that what you thought you looked like?

To some extent, although at that time my self-image was not such that I thought I was really attractive at all. Throughout the relationship, Neil lauded me and constantly told me how absolutely gorgeous I was. I had never known it at that point, and even today I don’t trust it. But that was his impression of me. It was not my impression of myself. I thought I was reasonably good-looking, and I was trying to mold my image to be like an Upper East Side gay—not even Upper East Side, a West Village gay. But that was only because it was the only thing I knew, in terms of the gay world, at the time.

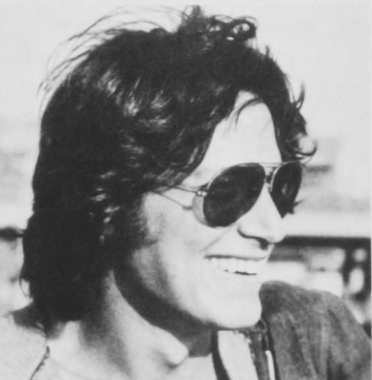

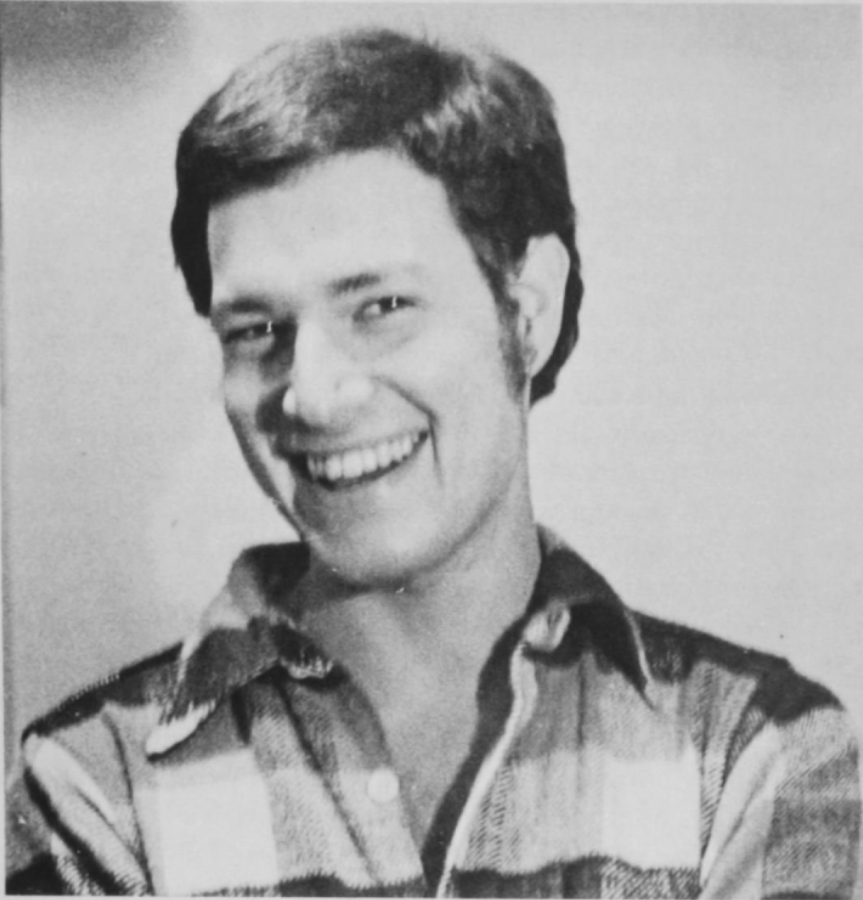

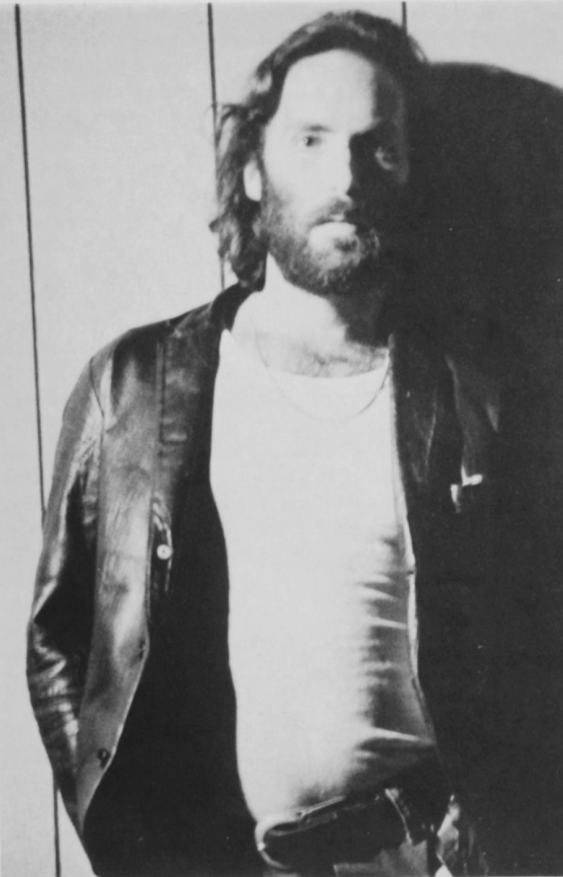

Picture number 2 is Neil when I first met him ... a week after I first met him. We met in a writing class at the New School. And Neil approached me. In fact, I spoke to Neil first. I knew that he was gay somehow. He was in the back of the room, and I saw him staring at me as I was leaving, and we walked downstairs, didn’t say a word to each other, walked out into the street, and I knew he was following me; I knew he was looking at me; I knew he was gay. I don’t know how I knew that. And I said, “How do you like the professor?” Then we started talking, went to a coffee shop on Christopher Street—I didn’t know what Christopher Street was at that time. He said later he was testing me, to see if I were gay, and if I were picking up on what was happening all around us. I didn’t. We sat in the coffee shop and after about twenty minutes he asked me if I was straight. And I said not exactly, and went into the whole history of what was happening to me at that point. I was seeing a woman who was living with a guy who was involved with another guy, and it was very sordid. I was not attracted to Neil ... at that point.

You were not attracted to Neil?

Not physically. At all. I mean you can see this is what he looked like then. And you’ll see, later on, what he became. I knew at that point that I had a certain fantasy-type man. He was dark, hairy—Neil was hairy, bodily hairy. But that didn’t register at the time. So I wasn’t attracted to him. He looked very different when I first met him than he looked throughout the relationship. He didn’t have his beard. Because his hair was short, it was much lighter than it appears to be when it’s longer. Anyway, he invited me to his apartment, not that night—I didn’t want to go that night—but I guess a week later I went to his apartment. I wasn’t attracted to him; I walked in and within five minutes he jumped on me. And I went through this whole thing—I said, Wait a minute! What are you doing? What is this? I mean, I knew this was a sexual arrangement, but like … wait a minute. Like wait. Hang on. And obviously there was something operating. I was attracted to him on some level which didn’t present itself to me as physical or sexual at all at that point.

And how old was Neil then?

Twenty-five. Our birthdays were coming up relatively soon. I turned twenty-two and then he turned twenty-six.

What does he look like to you in that picture?

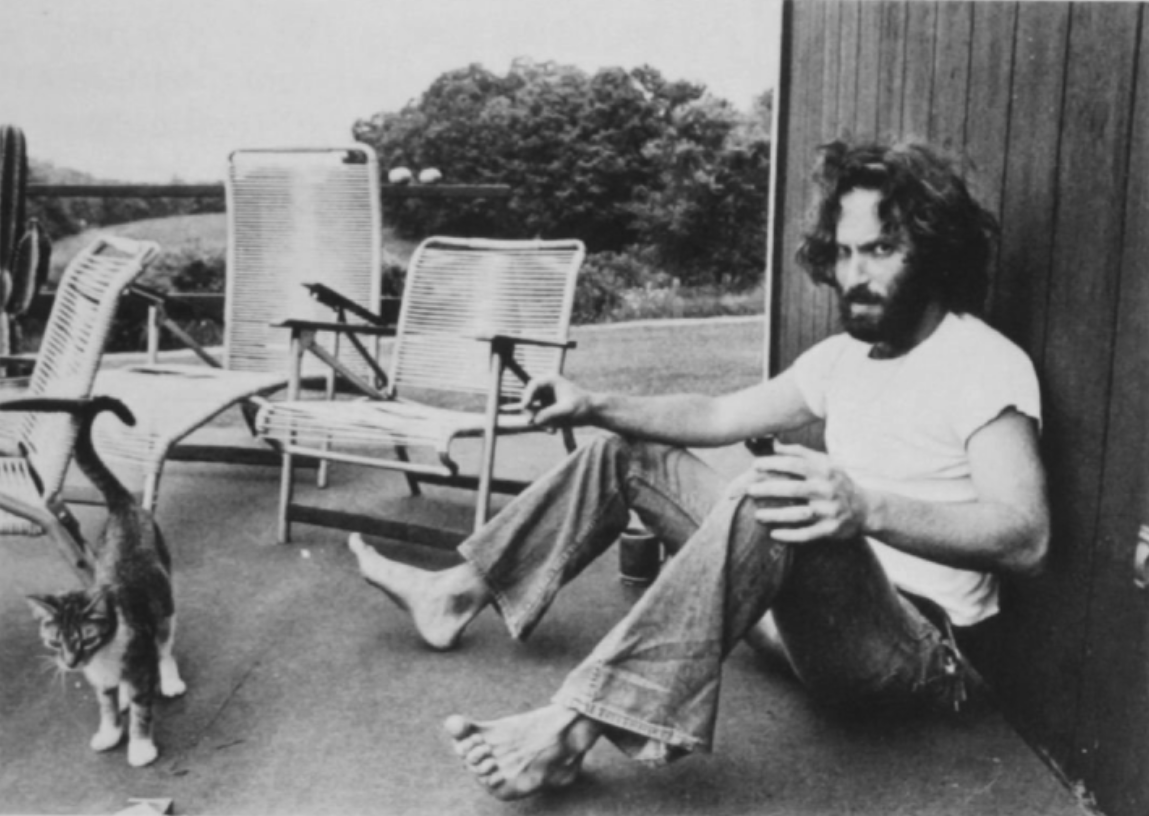

He looks like he came out of the fifties. He looks like a sensitive child. Yeah, a sensitive child. He does look very natural in this picture, which I really liked. I guess I responded to that. But somehow when he spoke about life, his general philosophy was really incongruous with what he looked like. Because he really does look like he’s out of the fifties in this picture. I couldn’t relate to the incongruity. It’s also interesting. This is an aside. This was me. [Photo 3]

About three weeks after I met him I got my hair cut. That wasn’t what I looked like when he met me, that was after he met me. And he went through a period of about two months of not being very attracted to me because I looked ghastly at the time, incredibly different. I hated what I looked like at the time. I was looking for a job and I figured the only way I would get a job was to get my hair cut. And I looked very preppy, looked … very, very, very young; I looked about eighteen. Very clean, very asexual. I felt very asexual. No—I felt that I looked asexual.

How did Neil react?

He went with me to get my hair cut. I was freaking out and he was very very cool about it, didn’t say a word, and he was very supportive after. We were walking down the street and I was looking in windows and freaking out because I couldn’t relate to it at all. And he was saying, “It’s all right, it’ll grow back.” Only two months later did he tell me that he couldn’t stand it and that I had lost my attractiveness to him.

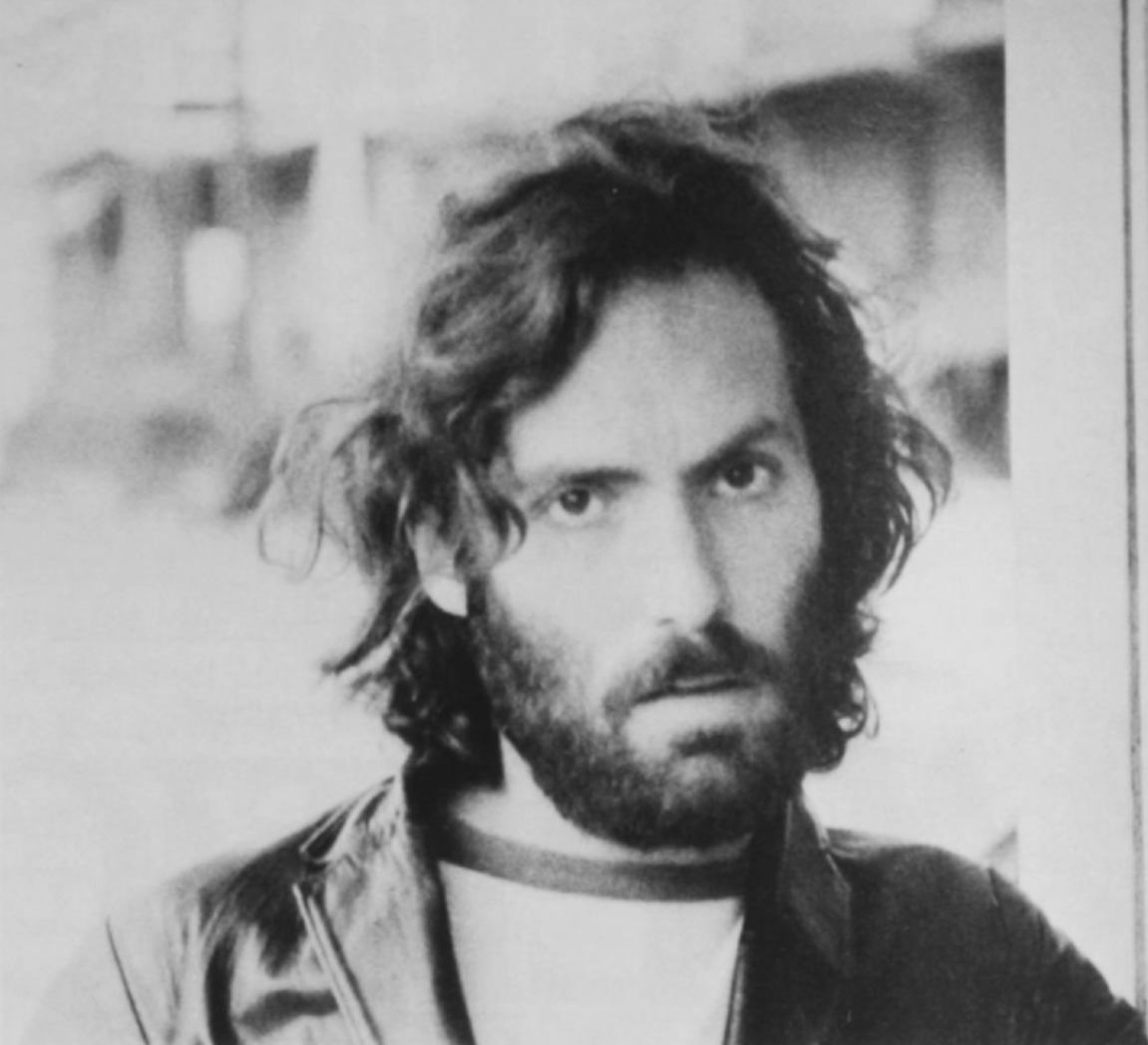

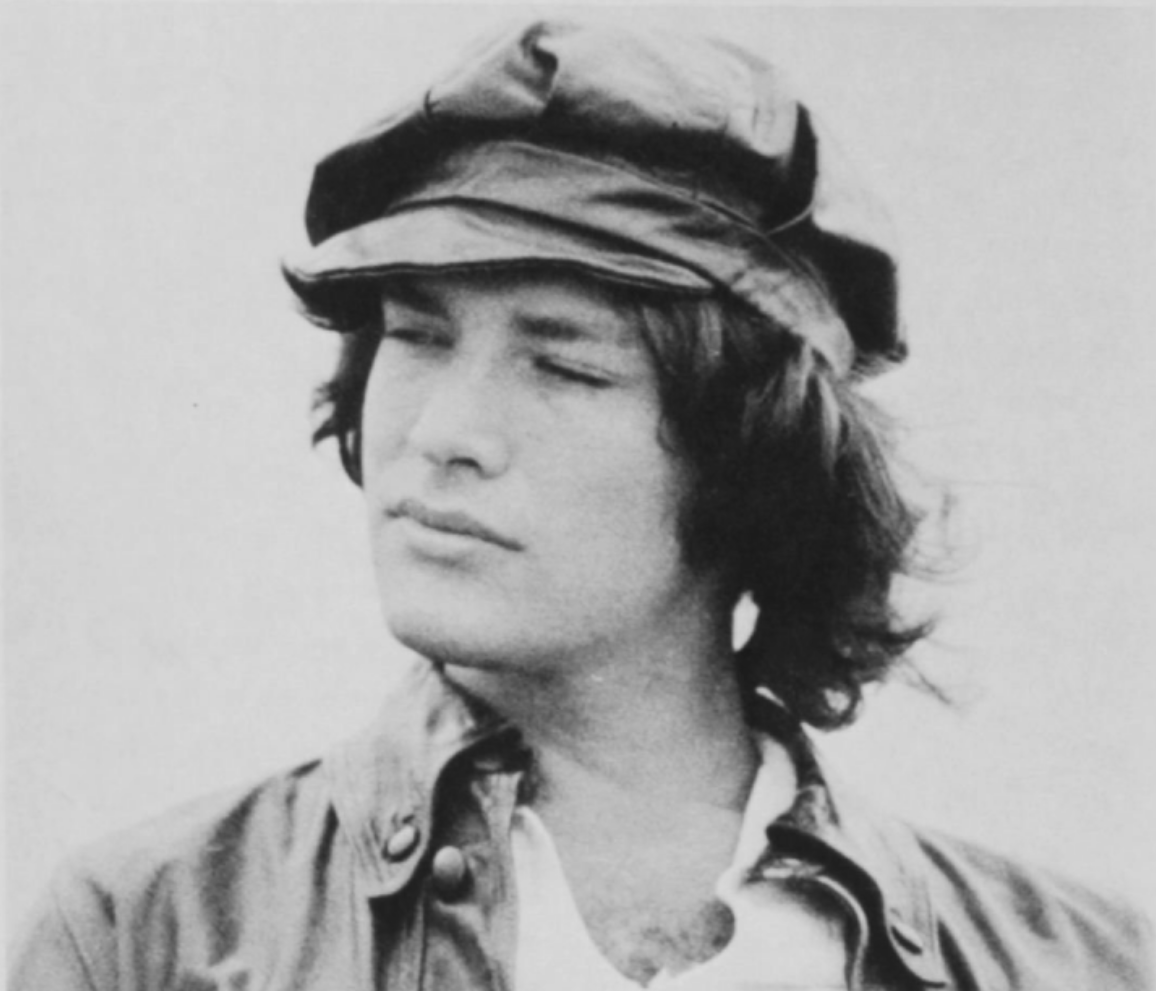

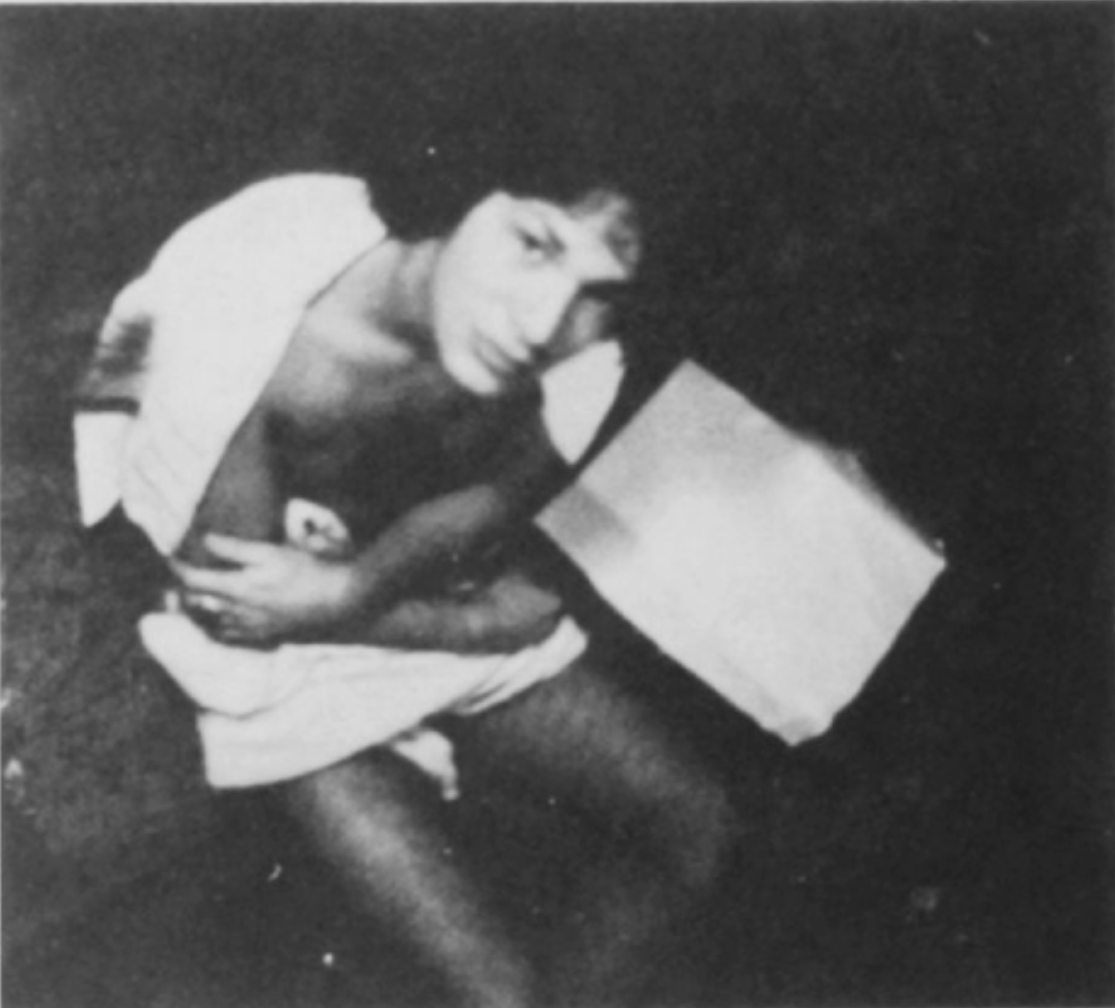

The fourth photograph was taken about a month or two months after I met him. His hair started to grow and he started to grow his beard. One thing I was attracted to about Neil was that, even though his hair was very short and he was shaving, he had this very thick stubble, and I liked that a lot. I’m very attracted to it, sexually. I guess I started really falling in love with Neil about a month and a half after I met him. I even remember the day, I remember the moment, I remember what happened and what happened to my feelings when I fell in love with him. And this is…

What was the day and what was the moment?

I’d say it was a month and a half after I met him. I was at his apartment, it was late afternoon. It was autumn, it was about this time of day ... just about this time. December first, the end of November. I had come in from looking for a job. We were lying on the couch; I don’t think we had made love but we were just lying in each other’s arms. It was starting to get dark. There was a very beautiful light in the room. And all of a sudden I realized that his body felt absolutely ... it was like the perfect answer to all my needs. It was warm ... At that point I was very needy. His body felt perfect. It was perfect. It was furry, it was warm, it was ... Mommy and Daddy. The embodiment of Mommy and Daddy. This was how I felt about it at that point. All of a sudden I had all these romantic fantasies of this being what it was like in London or Paris in 1920, you know, on an autumn day. I mean it was very literary, the whole mood of what was happening. And this is what it was like. And I fell, I literally fell, I felt myself sink, felt myself submitting to the feelings which were greater than the control I had over them. And I fell in love with him that day. We were just lying in each other’s arms and kind of laughing and talking, and in fact, he was asking me how much I loved him. I was saying, “I can’t tell you that, I don’t know that, I don’t know that I love you.” And it was ... like a ... right after that conversation that all this happened, this feeling emerged. I didn’t tell him about it that day.

Right after that we went to the store to shop; he was going to make me a banana curry for dinner. And I was real impressed with the fact that he could make a banana curry. I’d never even had a banana curry. I’d never known anyone who had made one before. I guess that was a symbol to me, an aspect of his worldliness which I also was seduced by; he had traveled a great deal, seemed much more worldly and much more experienced than I was. I guess all these things … contributed to that moment. This picture [Photo 4] was taken at that time. His beard had started to grow, his general image was darker. You know, if one were to describe Neil, one would say he’s dark, kind of hairy. I was very sexually attracted to that. Around that time I started to have sexual fantasies about him when he wasn’t around, masturbatory fantasies. He was beginning to look more and more like my ideal fantasy image. And it’s hard for me to say which molded which ... whether the ideal fantasy image was a priori and had existed before I met Neil, or if it was formulating as my relationship with Neil was formulating. Does that make sense? That distinction?

Yes.

Also this photograph is revealing in terms of certain symbols. It was taken in the steam and it’s real cloudy and nebulous and he’s almost an apparition, a kind of dark satanic apparition coming out of the steam and smoke. And that’s sort of how I was feeling about him, too. My own feelings were very nebulous, confused, and this presence was emerging, in my feelings, this kind of dark, satanic presence, which was taking control of my feelings, or making me lose control of my feelings.

Was this picture taken after you realized you were in love with him?

Yeah. Very soon after. A week after, three days after … Throughout the relationship, Neil also had this metaphor about us together … he was Night and I was Day, and that he represented all that was dark and evil and mysterious and intriguing about the world, and I represented goodness and daylight and sunshine and all that. I resented the metaphor throughout the relationship, but I think I resented it because there was probably a lot of truth to it. Okay … [long pause]

As I’m talking about this, I have to say my anxiety level is rising. I’m sitting here sighing a lot, and words … if we were in a more comfortable situation … words would come much more easily and they’re not. I’m finding it harder to get to real specifics in describing us. These photographs are summoning a lot of feelings that I shouldn’t have put away [laughter] …

Did your parents know you were gay at this time?

They found out about a week after I moved into Neil’s apartment. My mother was on assignment and was in New York for two days. We were having dinner at my aunt’s house and she asked me if I could spend the next evening with her, go out to dinner or something. I explained that I had to go to my group meeting and she asked what that was, and I explained it was a consciousness-raising group where we all tried to share common experiences and understand our common victimization. When everyone left the table she asked what kind of people were in this group. I said there was a doctor and two professors, people like that. And she asked how old were they? I said the oldest was forty-two … and she looked at me and said, “Are you the youngest?” And I said, “Yes,” and she said, “Are they all men in your group?” And I said, “Yes.” And she looked at me quizzically and said, “Are they all right?” At that point I almost threw up and I said, “If you mean are they gay, yes, they’re gay.” And she—her look was one of astonishment, fear … panic. She told me it was a lie, that it was going to destroy my future …

What was a lie?

That I was homosexual. It’s called negation. She totally negated it. She asked me if my roommate, who was Neil at that point, was gay … and I told her yes.

Had she met Neil?

She had not met Neil. She just knew that I had moved into an apartment with this roommate. At that point she said, “Daddy is going to come to New York and take you out of that apartment.” Well … I burst out laughing. You know, she couldn’t possibly believe that he could do that. Anyway, her reaction since then has been one of total negation of my sexuality.

What do your parents do?

My mother is a professional photographer, my father is an executive. They live in Florida. I grew up in Florida. They’ve had gay friends for as long as I can remember ... And they’re always Left on most issues, very liberal ... I was shocked at their reaction ... my mother’s reaction. My father reacted differently. My father called me up later that evening after he received a frantic call from my mother announcing my homosexuality. He asked me if this was really true, and I told him yes. And he couldn’t understand because of my history. I guess I had girlfriends in high school. I had brought a girl home from college one vacation. And they assumed I was perfectly heterosexual ... I mean he couldn’t understand it at all. He came to New York periodically after that, just on weekends, you know, having dinner with me and taking walks with me to find out more about homosexuality. Ironically enough—or it’s ironic to me—it’s my father who really took the interest in finding out, and as a result, we have a much closer relationship.

He’s revealed things about his life and his marriage to my mother, things most fathers would not reveal to their sons, as a result of trying to find out more about who I am and why I have this ... um ... um ... aberration, as my mother terms it. It’s adhered our relationship, my father’s and mine. Unfortunately he had to be the liaison between my mother and myself on this issue. That had a great effect on my relationship too ... in terms of my never quite feeling like the relationship was sanctioned. Not so much culturally, but very personally. On some level my parents couldn’t ... my mother wouldn’t even acknowledge the relationship.

Did either one of them ever meet Neil?

No. At one point they came to New York for a week. They came about three or four times a year. One time—this was about a year after I moved in—I told them I simply wouldn’t see them unless they had lunch with us, to meet Neil. My father agreed. He agreed unwillingly—he told me he was uncomfortable about doing it but he felt it was very important for me, so he agreed to do it. My mother refused. So I told her that until she agreed to do it, I would not see them. And I didn’t. The next time my father was in New York he paged me through Neil and me out to lunch but I got the flu [laughter] ... so they ultimately never met, and I guess I was as uncomfortable about their meeting Neil as they were.

One time they went to an opening at the Museum of Modern Art and I was invited to go to this opening too. A friend of mine had another ticket and I decided that if my parents wouldn’t meet Neil, at least Neil could see my parents. So this friend brought Neil to the opening. I was going there with my parents and pointed them out to Neil and he followed them around for about two hours, listening to their conversation.

Did Neil’s parents ever meet you?

Yeah, his parents met me.

Did they know Neil was gay?

Yeah, they knew that Neil was gay. They had dealt with that revelation when Neil was seventeen, and it took them about five or six years to accept the reality that he was gay.

They met me and knew that I was Neil’s lover; they invited me to dinner on Friday nights at their home. I went to their family seder ... his mother used to call me up and wish me a happy birthday ... and ... um ... I guess my rapport with Neil’s mother ... I guess the interaction had mostly to do with my mother’s reaction. I would tell her about my mother’s reactions to my sexuality and she being ... having great expertise in coming to terms with Neil’s sexuality, she felt she was an authority on how mothers should deal with their children—their son’s sexuality—homosexuality ... so she would give me advice on how to deal with my mother. That was pretty much what we talked about. His father and I would have very civil exchanges, very warm, very nice. We didn’t talk much, but I felt like one of the family; they were my in-laws.

So did you feel a certain amount of sanction from his parents’ reception?

To an extent. It’s complicated to a point because Neil’s parents never quite accepted Neil ... as a person. They sort of—it’s as if they had given up on Neil and hence—you know, they just accepted Neil as who he is—um, without their ultimate support and approval. Because of that, it was easy for us to be who we were with his parents. And somehow I recognized that ... I recognized there was a certain kind of sanction of our relationship that was not the same kind of sanction, or approval, I had been brought up to respect, I guess ... God ... [laughter]

It makes sense, though.

It does ... You know Neil never lived up to his parents’ expectations. They wanted him to be a businessman, have a nine-to-five job. Neil doesn’t have the externals that parents can brag about. And I’m still locked into some of those prescriptions. You know, it’s important for me to hold a respectable job; a job that ...

Gives you public standing in the world?

It’s not so much that ... a job that means something in the world, a job where I could be creative and useful in some important way. In a broader sense, more on the cultural level than on an individual day-to-day bureaucratic level. My brother is a doctor, my sister is a lawyer. They’re approved of by my parents. I’m approved of—to a point—in terms of my job now and in terms of what I ultimately want to do with my life.

Your job now being?

An editor in a photography publishing company. I work for a magazine, a quarterly of photography, and for a publisher of quite distinguished photography books.

Did you have any problems with the fact that while Neil also obviously needs to have creative, meaningful work, he doesn’t need to have it socially sanctioned by any institutions, doesn’t need the reassurance a nine-to-five job gives you about your place in the world?

Not at first. I have enormous respect for Neil as a writer, and Neil’s ambition to become a writer. It started bothering me later on that he wasn’t interested in the same cultural reference points that I’m interested in. For instance, I would be very impressed if he wrote essays in The New York Review of Books or the Partisan Review, or something like that. I guess I’m enamored with certain publications which are highly revered in academic communities and professional communities—intellectually respectable. Somehow if he had started writing for those kinds of publications I would have continued to admire his need and desire to write. Unfortunately Neil worked on two novels while we lived together, and worked earnestly and continually for a period of months. But after the first draft, four months or so, he’d give up and put it away. And eventually I started to realize that he didn’t have the tenacity that I had initially admired ... uh ... I don’t know if that answered the question. It didn’t bother me in the sense that it would bother my parents if I didn’t have a job with a name institution. I was brought up on those things in the world which are prestigious and by the virtue of that prestige they have some content. I realize that that’s not true, most of the time; but, somewhere in the back of my brain, is my parents’ indoctrination. I can’t help but apply that to ... Neil’s writing ... at this point.

Did you get exasperated because he didn’t finish?

Yeah, I would get annoyed. Neil would complain that he was not doing any work, he would complain that he was not being published, and I would explain that he wasn’t being published because he wasn’t working hard enough at it, that he couldn’t expect to write a novel in four months. He can’t expect to write one draft and say it’s finished ... or even to have anybody read it, or want to read it. You know it takes a lot of work. And I started to see in Neil the desire to publish more than the desire to write, somehow ... and I started to really fundamentally question what it was that was motivating him. I mean in terms of how he saw himself, who he thought he was, and whether there was some real validity in how he was billing himself.

How did you feel about Neil doing the gay radio show and being a personality in that particular, not quite respectable, subculture?

Well, I actually very much admired that not quite respectable subculture. I mean the sixties had a great effect on him. When Neil first started doing the radio show, I was real pleased. I thought it was a wonderful format for him to talk about a lot of his theories, a lot of his own experiences in the gay world. Somehow I thought that would be very helpful to people, and he had some very good ideas and made some very good connections in terms of songs and articles he’s read and analyses he’s made about gay culture. But eventually I started to see Neil enjoying the fact that he was a personality more than the fact that he was there on some kind of mission. And I saw the job as somehow being somewhat evangelical for the gay world. Not as a missionary, but as a spokesman, a spokesman about gay culture. Somehow Neil started to get off on his radio persona and started to trip out on the fact that he was this personality rather than someone who is there for and with the responsibility of the gay community in mind ... It started to annoy me [sigh—long pause] ... well ...

Did you think he respected your work?

Yeah, I think he did. But I worked less than Neil, in terms of my own work, in terms of photographs and drawing, partly because I had a nine-to-five job.

How about the nine-to-five job? Did you think of that as a grubby way to make money or ...Well I thought I needed the job. I had to make money. But I also saw the job as the beginning of the ladder of my career, related to my career, which deals with photography. I worked at Time-Life, in the picture collection, researching photographs, editing photographs, looking at photographs ... so I was connected to what I wanted to do. Still I was there eighty percent because I had to live, to eat, and, as long as I was making money, I thought I should make money at something which was going into my lifework. But it gave me very little time to do my own photography or to draw. I was also in graduate school. I went to NYU at night.

In what? Photography?

No, comparative aesthetics, which was a bit esoteric, abstruse. So, I was working nine to five—actually ten to five-thirty—and going to school two nights a week, and working very little at my own work. Neil had a great deal of faith in my talent. He believed I was really talented, but I was too young for him to take seriously. He could write off my lack of discipline because of my being young, in my early twenties, and just trying to get settled in the world.

Was his response to your photography useful, beneficial, stimulating—?

No, his response to my photography was very personal. Particularly given the fact that most of the photographs I took while I was living with him were of him. It was hard for him to have any real perspective on the photographs as photographs. Rather he viewed them as photographs of himself. And his criteria for looking at the photographs had more to do with whether or not he liked what he looked like and not whether or not he liked the images.

How about your response to his writing? Did you read what he was writing? I mean, there’s a terrific parallel: at least one of Neil’s novels was about you—as your photographs were of him.

Neil began that novel three or four months after I moved in. I would read the chapters as he was writing them, and I’d think I was giving him real critical perceptions about the writing—when in fact I was responding to me, the character “Philip” in his novel. Pretty much in the same way he was responding to my photographs of him. I’d talk about sentence structure or pretend to talk about sentence structure and all of that. What I was really talking about was that I didn’t like how he portrayed me. Neither of us was a very good critic of the other’s work, to be sure. A lot of that has to do with the fact that both of us were in each other’s work. He wrote a novel about me, I photographed him. We were very taken with each other. [laughter]

You said Neil didn’t have demanding standards about your work because he thought you were young, fooling around to some extent, not settled down. Did that ever bug you?

No. It was sort of an excuse I liked. As much as Neil accepted the fact that I was young and hadn’t really settled down into my craft, I was going through constant frustration, turmoil, and guilt from not working as much as I thought I should. Part of my reaction to Neil not working as much as I thought he should had a lot to do with projection—it was a total projection of my own guilt. Absolutely. [long pause]

You want to go on to the next photo?

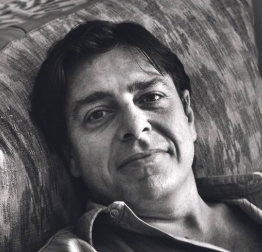

Okay ... This photo [Photo 5] is probably the only photo I really love of me, a photo that Neil took. First off, I think it’s a photo that looks more like me than any other. I also think it’s a very flattering photograph. Of any of the pictures Neil has ever taken of me, it comes closest to what I think I look like. [pause] I guess when I said it’s flattering I also think I’m pretty good-looking. And that picture sort of reinforces it. I also have to say, as an aside which is relevant, I printed this picture, and as I watched it emerge in the developer, the immediate flash feeling I had was that I wanted to fuck this person ... who was me. (Heh) And ... I didn’t know what to do with that feeling. Like I didn’t know just how to deal with it at all.

This picture was taken in the forest in Connecticut, where Neil and I spent a weekend. Someone Neil knew two years before called him up and invited him up for a ménage with him and his lover. And Neil said he had a lover too. The guy never met me but said he trusted Neil’s taste, so the two of us should come up and spend the weekend in this house with these guys and have this wonderful ménage all weekend. So we went up. I was incredibly frightened by the whole thing. Neil and I had had a ménage six months earlier, which was a disaster. I freaked out during the first ménage primarily because the two people were more turned on to Neil than to me.

At the time of this picture, we had lived together for about six months. I was very frightened, I guess, because we were going under the aegis of this guy who had had sex with Neil two years before and really thought Neil was a hot fuck, right? So I knew this guy was very turned on to Neil. I also knew at this point in our relationship that Neil and I were very different types, and that we attracted very different kinds of people. And chances are, if this guy is real turned on to Neil, he would not really be turned on to me. Which means that I was putting myself in the position all over again of the ménage of six months earlier, in which I totally freaked out. [laughter] And started seeing a shrink—or I guess that was the catalyst for starting to see a shrink. So we went up to Connecticut, and I decided to do it just because I had to test myself. But it turned out the other guy, who had never met Neil, was very much turned on to me. And when we finally had ... a sexual episode, we paired off—in the same bed, but the other guy, Bob, was with me and Frank was with Neil. And Bob and I got very into it. Neil got very threatened, ultimately, and the next morning—Neil and I slept in another bedroom—and the next morning when I woke, Neil was still sleeping, and I went to the other room and had sex with the guy again, then came back into our bedroom, and Neil had to have sex with me. And I see it all having to do with his being threatened. Later that morning we went out for a walk, and that’s when this picture was taken. In the woods it was very, very idyllic, very romantic; it was a real rapprochement.

He didn’t say anything about being upset?

Not until a few days later. He mentioned the fact that he was very threatened ... And, okay, one of the things I was very pleased with was the revenge aspect on my part. I didn’t know it would work out the way it did, but I was glad it did because I wanted Neil to know what it felt like to be that threatened. I wanted him to know what it felt like to be anxious, to fear that kind of loss, to be sexually threatened, to have his whole sexuality really tested ... because I had felt that way six months earlier in the other foursome we had. And it gave Neil a lot of control over my head, and a lot of power, sexual power that I didn’t feel I had. And in this foursome in Connecticut, it was the reverse. I had a lot of sexual power and I really liked that power and really needed that power. One of my general operatives in life is sexual; I see myself as very sexual, and for the first six months of our relationship I didn’t feel that sexual power base. I was very, very, traumatized about that. Neil photographed me as this very Botticelliesque figure. And my theory about it is that, because he was so threatened, he had to create a fantasy or an illusion about me, and he was in love with the fantasy of me more than he was in love with me, or more than loving me. He also loves this picture of me. He adores it ... The sexual dynamic of the relationship was that Neil couldn’t be entered. I mean he had a very hard time relinquishing control, sexually. Neil’s sexual dynamic is generally that he has to be in control. Neil’s the first person who ever entered me and I really enjoyed it. I mean before that, two or three people had tried and I couldn’t. I just couldn’t let it happen. And Neil entered me the day after our first foursome when I needed him ... I mean ... I really felt threatened by the fact that he had been more attractive to the other people.

And when he entered me I guess I was really receptive and really needed him. I guess pretty much throughout the relationship Neil entered me and I have constructed all these dichotomies about what it means to be the penetrator or the fucker, like “he fucks someone over,” or “he’s getting fucked over.” And I started to construct these hypotheses in my head. I started seeing myself as the person who was being fucked, and thus being fucked over. The implications are much broader in terms of constructing roles. I was the woman in the relationship and he was the man. And that entered my whole life and permeated my life in terms of how I saw myself. I started seeing myself as very feminine. I couldn’t fuck, even when I went to the baths or to pick people up, I lost all my confidence and felt like I couldn’t fuck as well as Neil could fuck me; in other words, I couldn’t fuck, hence I just had to be fucked. And hence I lost my manliness, my masculinity; I became very feminine. I felt very feminine although I never really adopted feminine postures per se, nor came off as particularly feminine, but certainly that was my self-image for a long time. It was very destructive in terms of the relationship.

As I was feeling all these things, concurrently I also had a lot of political theories—gay political theories—which had to do with not operating from the road maps or guidelines of heterosexual sexual relationships. I mean not having role definitions. We had to create and construct our own, which had nothing to do with male-female, dominant-passive patterns and all of that stuff having to do with a lot of heterosexually defined relationships. Yet I was operating from heterosexual patterns, constructing male-female operatives in the relationship, which went against everything I was spouting. Which ultimately ended up in making me very schizzy throughout the relationship, because emotionally I was operating on very different grounds than my theory. Aside from that, I always saw Neil as much more sexual than I, because I felt that I was very feminine and I wasn’t turned on to that. And since I was not what I was turned on to, I felt like I wasn’t sexual at all.

Although, when you saw the photograph …

... although when I saw the photograph I wanted to fuck this person. Which created a dual feeling for me. I liked the idea and hated the idea at the same time. Because it meant that I was very fuckable, which meant that I was very feminine. Which reinforced all the feelings that I had about myself, the negative self-image. Yet I liked what I looked like, and I liked the fact that I could attract somebody to fuck me. So I was very schizzy, to be sure.

But you think this primarily came from Neil, this feminizing of you?

No, it came from me, but it came from my view of Neil. I mean it ultimately did come from Neil, although I also did put Neil into the role. But it was a role that Neil wanted to be in. I don’t know if I’m more responsible for it than Neil is, putting himself in that role. Because Neil’s image of himself is very masculine—very—like he’s the stud. Sees himself that way. Very experienced; very worldly; very self-sufficient. He can really take care of himself. This is Neil’s image of himself.

But now part of the problem is that I resented that a lot because, although I was very attracted to all those things in Neil, and he was, in fact, many of those things, I wasn’t, and I knew I wasn’t. I don’t look like a stud. I mean I have a very different look. I wasn’t self-sufficient when I met him, I was looking for a job, I was being supported by my parents. I didn’t know a lot of the things Neil knew; he knew a lot about the dynamics of the gay world I didn’t know. He had studied in London, had traveled many places I hadn’t been, stuff like that. All those things I wanted to catch up on; I wanted to be where he was. I wanted to feel that self-sufficiency, that self-containment; I wanted to be the stud. Because I was attracted to all that. And I have a “narcissism theory” about being attracted to all that I want to be. But I can’t deal with the gap between what I want to be and what I am. I mean they’re two different things. I think in fact at this point today I’m much more what I want to be than I have ever been, and closer to that ideal fantasy that I have, that Neil fulfilled. I’m also the age Neil was when he met me. I’m now twenty-five; he was twenty-five when I met him.

There was a lot of competition, of wanting to be what he was, which is because I wasn’t there yet. The competition manifested itself throughout in seeing Neil as older than he was and his seeing me as younger than I was, and in terms of my seeing myself as more feminine and hating that.

Did you ever grow a beard?

A few months after I moved in, I started to grow a beard and I looked absolutely ridiculous. [laughter] I mean I looked absurd. I looked like I was trying to become Neil, and I felt like I wanted to become Neil. It made me real schizy. I mean, it just went against everything I am. I couldn’t wear the beard; I just looked ridiculous. That’s all. Looked like I was a fourteen-year-old child trying to look eighteen, or twenty.

Want to go on to Neil?

Yeah. This photograph [Photo 6] of Neil was taken the same time as the nude of me in Connecticut. Looking at this picture, and just seeing it as a stranger, it looks like someone who’s really horrified, who’s just in absolute shock. Knowing what’s going on—the foursome in Connecticut, same context—I see Neil psychologically shaken up. He must be really threatened, and not posed there at all. I mean he really did curl his feet up as the cat walked by, and he’s real scared ... totally thrown off balance. And that’s how I saw Neil at the time. Neil didn’t talk about it; he became really introverted and real hostile to the guy who was attracted to me. That afternoon the three of us—not Neil, the other two and me—all went for a swim in a nearby stream. Neil refused to go. From that morning he wanted to leave. He couldn’t take it. We had to take some late-afternoon bus or something. They were preparing dinner, but he just wanted to get out. He was very upset. But wouldn’t talk about it until a couple of days later when he said he was threatened.

The next three pictures, I guess, visually summarize the three components of Neil I fell in love with or continually loved about Neil. This picture [Photo 7] shows a kind of resolute vulnerability which Neil didn’t allow to come through very often. And when it made me as a result, because he wouldn’t allow it to come through. One of the things I constructed in terms of the role I put Neil in was the fact that he was very self-sufficient and he wasn’t very vulnerable. Which I knew wasn’t true, and I knew that somewhere he must be a real person with real feelings and real vulnerabilities, I didn’t see it very often. I mean he wouldn’t let it come through very often because he was reinforcing this role, this desired image he wanted me to have of him, ’cause he liked the image I had of him. All right. But one of the things I also remember was ... Neil had a smile, the first month that I knew him, that was very ... he never had that smile again. It was a smile of lack of assurance. It was a tentative smile. And it was the sort of thing I’ve never seen him do since ... ever ... I only remembered this recently. The smile. I’d forgotten about it for about two and a half years. The smile was his vulnerability. It was a half-smile and it was really tentative and it was real scared.

This picture to me reveals that same kind of vulnerability. It was only that vulnerability that allowed me to fall in love with him because I knew that he was a real person and that he did need me as much as I needed him. And I needed to know that. This picture was taken—in fact all three of these pictures were taken—on a trip to Provincetown. It was in the early fall, maybe a year after we met. And we were already living together for about nine months, ten months. Neil had an accident; he was hit by a car that August. He was in the hospital for about a week. I was really devastated by the fact that he was in the hospital; and every time he said he was in pain, tears would come to my eyes. He was very vulnerable at that point. This trip was in late September, a kind of recuperation, convalescence from the accident. And so he really needed me at that time. He couldn’t walk around for long periods without getting dizzy; he was hit on his head and all that. This picture was taken at that time and he looks very vulnerable. I mean very real. It’s a direct honest picture.

Most of the pictures I have of Neil are posed because Neil usually posed in front of the camera. Whenever I lifted the camera up to my face, he would immediately assume a pose.

But Neil enjoys poses, he enjoys doing that even without a camera being around.

Yes he does that without a camera. Part of Neil is posing. It’s also the part I didn’t like about him, even though I liked some of the postures ... Okay, the picture of Neil. A vulnerable picture. It’s sort of indicative to me of Neil the child, and in our relationship we did a lot of baby talk. We had our own language which we used to talk in. And we had pet names for each other. He was Baby Ween and I was Ween Duck. We had voices for these characters. We also had a menagerie of invisible animals and people that used to go to bed with us. [Heh Heh] It was very endearing in a lot of ways, and it was, I guess, one of the unique manifestations of our intimacy, in that it was our language and only ours, and we could have sex with other people, we could talk about everything with other people, but that was ours. It was something solely ours. And I saw Neil very often as a child. Contrary to my whole image of him as a man, he was this little boy. I loved that image. Adored it. I also had certain theories about that, about the three-year-old camaraderie, like a new pure friendship; I don’t know how to describe it. Very often I thought of us as little children, you know, who really loved each other in a real pure way and just played and had a good time with each other. And I saw this image, had this image flash of Neil very often as a three-year-old kid and used to wonder very often what Neil had been like as a three-year-old. And I had little entertaining fantasies about what he must have been like. What they’re about psychologically I’m not sure. But I loved it when we did our baby talk.

This picture sort of represents to me the three-year-old Neil, at his most vulnerable, really needing me—that has a lot to do with it, I guess, really needing me. That’s why I constructed those daydreams. I guess he didn’t really need me very often. As the relationship progressed, we got more and more into talking baby talk to each other. And a lot of times we’d use that as the excuse not to deal with other things which should have been dealt with. It bordered on being psychotic, I think. He would call me at my office during office hours. I’d answer the phone and say hello and he’d answer me and say “Hi!” in his little baby talk kind of thing which I can’t mimic. And I’d talk to him in a normal voice but I’d get off the phone and someone in the office would come up to ask a question and I’d say “Vat? Vat?” in my baby talk. It became a little strange. Just slightly out of control, I guess. But it was very endearing, it was very unique to our relationship. It was the one manifestation of intimacy. That’s why I like that picture. Also, this picture is a reminder of Neil’s relationship with me at the beginning; the fact that he wanted me really badly and his smile was hesitant enough ... and vulnerable enough ... to make me realize or to make me see that. I don’t ever talk about this ... Christ ... I guess I just needed that reminder, you know, that I meant a great deal to him and when he presented his vulnerability, it was a sign to me, an indication that he really did need me, and I needed to know that. He didn’t communicate that as often as I needed it, and I guess I would have liked that. So I love that photograph for that reason.

[Photo 8] is Neil in front of the entrance to the house we stayed in. I guess in this picture Neil’s posing. Definitely. I mean he’s wearing a costume, a kind of thirties, twenties, Paris-literary costume like Proust, Pound, Hemingway ...

Neil is very much fascinated by history ... he studied history, and is very taken with literary history, and models himself after many historical figures. This photograph is representative of that, and of his general eccentricity ... I see him as very eccentric. He has a lot of habits which I found fascinating and appealing, although they’re not habits, more like hobbies. Things which I had no interest in, but I was fascinated by the fact that he was interested in them. For a period of time he collected old left-wing political buttons. He would walk around the city to various stores and pawnshops and collect these buttons. And I was really intrigued by the endurance of his interest in this type of thing. He was really into it full of force. That intrigued me in terms of his character, in terms of what made him the person he was.

He’s also into collecting first editions of books and he’s become very friendly with a number of book dealers in the city. He reads a great deal, and he reads things which I’m not particularly interested in reading although I recognize they’re worthy things to read. He reads lots of biographies and I’m not interested in biography. But I’m impressed with the fact that he sustains interest in reading these biographies, and biographies about people I couldn’t give a shit about, like Horace Greeley, Edith Sitwell, and Alma Mahler. What intrigues me is the fact he can do that, that he’s interested in that. I guess all these things make him somewhat eccentric and hence somewhat glamorous to me. This picture really capsulizes it.

By eccentric do you mean bohemian intellectual?

To some extent ... that’s part of it. But that’s not all of it. There are other eccentricities. He’s a bohemian intellectual but also very aware of sociological processes and operatives in terms of the way the “real world” operates. He understands all of that and just simply rejects it ... being on the periphery of society by choice, not just by the nature of who he is—he chooses that. And this picture sort of summarizes that for me.

Go on to the third?

Yes, the third is much heavier for me [Photo 9]. This is the same trip to Provincetown. And this is Neil and I cruising. [laughter] I guess this is the heaviest part of our relationship. I mean the heaviest in that it’s the most unresolved and the most confusing for me and probably the most anxiety-provoking in terms of our mutual sexuality ... who Neil was sexually out in the world and who I was sexually out in the world and who we were to each other sexually.

I guess my analysis of Neil’s sexuality is such that he’s permeated by guilt about it, and has created a character, a sexual character, and acts out of the role of that sexual character. A character who does not have a lot to do with who Neil really is, but who works very well in the sexual world. I mean he scores very well, etcetera ... I also fell for the sexual character, which I could never reconcile. And I still can’t. This picture capsulizes his half-Satanic, demonic quality, the world of mystery, of darkness, of night, of evil, which I am very turned on to sexually. The hunter. This is Neil’s term, but it applies. I resented it for a long time. Neil is the hunter. And he’ll get what he wants sexually. This photo reminds me of James Dean, Brando kinds of figures: leather jacket, a beard, strong look and those piercing eyes, penetrating eyes, darkness—taking a walk on the wild side. I think throughout our relationship I resented my attraction to him sexually. Totally resented it. Why? Because it presented to me the fact that I could never be that sexual paradigm, the kind of person I was attracted to.

What?

That I could never be that kind of person; I could never be a demonic, Satanic figure, sexually.

Why does that bother you?

Because I wanted to be. Because somehow ... well, it had something to do with control and if one could control sexually, if one could make someone else submit sexually, apparently one had a certain control over oneself. I never felt that I had real control over myself. And here was Neil who could control me sexually, who could—I could get erections just by looking at him. I never felt I had that kind of power, that I could do that to anyone ... that I could make them get erections, that I could lure them into bed, just by the nature of my being. And Neil could do that to me. And I resented it; I hated it. I also hated the control he had over me. I mean I despised that control he had. I wanted that control.

I wanted the same control over Neil as he had over me. All right? And since I was attracted to that and that could control me, I mean that particular look, I wanted to have that kind of control. But I resented it, throughout the whole relationship. Despised it. [laughter] But loved it. It was a real dichotomy. It was schizy, to be sure. You know, ’cause I would lust after him and hate the fact that I was lusting after him. I also wanted to be lusted after; that was my big trip, to be lusted after.

How did Neil react to you, he didn’t lust after you? He just said you were beautiful?

Right. Like my feeling is that he aesthetically adored me. Aesthetically. But that’s very different from sexually. Even though I was the first person in his life he’d had any sustained sexual relationship with, he used to protest whenever I’d say “you’re not really sexually attracted to me.” He’d say, “that’s not true. You’re the only person I’ve ever had a sustained relationship with.”

It’s really complicated because Neil needs to be in control sexually, and when he loses control sexually he freaks out and can’t function. He has to be in control, which means that he has to make the first moves sexually. It gets complicated by the fact that I could have sex about three times a day. I mean, I’m real hyper-sexed. And if I don’t have sex I’ll jerk off. Neil doesn’t, he never jerks off.

Since I was always into having sex, and since I was lusting after him, I would initiate it a lot, which he hated. So I had to wait around until he wanted to have sex, which would be two to three times a week. That wasn’t enough for me. I wanted more. So it caused a lot of problems. I would try to initiate sex more often and he would reject it. And whenever I was rejected sexually I would immediately think it meant he was not sexually attracted to me.

Did you ever try to initiate it by being seductive?

Yes. And occasionally it worked. Neil has a lot of energy. Amazing amounts of energy. But he’s gonna burn himself out by the time he’s forty. He wakes up in the morning and within five minutes he’s up and he’s ready to go out and run. He does a lot of things in the course of the day, and he invests a lot of energy in whatever he’s doing. So, by the time I came home at night, he was already eighty percent burned out, just from doing whatever he was doing. Sometimes he had sex, very often he had sex during the day. That was the other thing. That was the real complication. I would get very pissed off and say, “you know, if you’re not into having sex very often but you have sex outside, and if I’m not getting enough, how come you’re having sex outside? You know, you’re not satisfying me first. And you should meet your quota in the house before you can go out and do it.”

If he could have sex with me once a day, then he could go out and have sex with other people. But he wasn’t filling my quota, yet he was still having sex with other people. And I felt it was symptomatic of something in the relationship and if he was really ... I mean this has all come out recently, after I moved out, that he was really scared of me sexually. He felt I had all this unleashed passion that he couldn’t satisfy, and hence he felt out of control.

In addition, you pushed him into the position of being this big macho …

Well he loves that. He wanted that position. Although it was an expectation on him that was beyond his ability to feel comfortable with. Another problem was that I wanted to fuck him, too, and I really resented the roles that had been constructed. I understand it—I think I understood it—in terms of his psychic construct and why he can’t relinquish control. And in terms of his not being able to be fucked by me—he never trusted me. He said from the beginning that he knew I was gonna leave him, and he felt that sometime I was gonna leave and he never trusted the fact that I was really there for him. And I understand ... to a point ... but I never believed that he really believed that, because I don’t think I could have given of myself more to any person than I did to him.

Now the problem was always arising from the fact that I never gave to him in ways that he needed, and I felt the same way about him: he never gave to me in ways that I really needed. Which is the ultimate destruction of the relationship, ’cause we just weren’t satisfying each other’s needs.

When he rejected me sexually, it meant two things simultaneously: one—he didn’t really love me, and two—I was not sexually attractive. I mean that, that—there was a major problem [laughter], to be sure. It was really a major problem. Neil on the other hand had a very different sexual operative, which was that it was easier for him to have sex with people he didn’t know. Also Neil constructs an illusion: the situation is equally important to him as the sexual act itself. If not more so. So that he can get off on dark streets, he can get off on seedy places, because they’re sexual. He can get off on tea rooms, because of the situation, the environment. The environment is as sexual for him as the physical sensation.

And not for you?

Well, it’s becoming more so, but not with Neil. With Neil, another reason it was hard for him to have sex when I initiated it was that I was already conquered. I mean there was no obstacle, it was no challenge. He couldn’t go through the whole conquest, which I think is integral to what turns him on. He knew he had me, he knew I would have sex with him any time he wanted. And, you know, big deal. And I’m very different. Even now I don’t like the conquest. Yes, I have to go through the seduction; yes, I have to meet somebody and talk to them and lure them into bed. But I would dispense with it if I could. If I had my druthers, I would just meet someone in bed rather than go through the whole process, the conquest. The seduction is intriguing. But that’s not what really gets me off sexually. I’m much more interested in what happens physically, in tactile sensations, in looking at the person, both during the sexual act and before it.

What about Photos 10 and 11?

Philip cruising. [Photo 10]

You weren’t really cruising, were you?

This is Provincetown.

Did you people cruise with cameras?

Yeah, sure. There was only one camera. We had to find somebody, and we didn’t know if we were gonna find somebody to sleep with together or if each of us was gonna find somebody and go off with them. And I think that night we didn’t find anybody, probably because I couldn’t handle cruising with Neil. My identity, my autonomy was totally threatened. My confidence was threatened because of competition, which I talked about before—

Did you do this, normally, the two of you cruising together?

No. Neil always wanted to. And I didn’t, I couldn’t handle it. I always assumed that everyone was gonna be more turned on to him than to me. In this picture [10] I look like an innocent trying to be real tough. I guess that’s what I look like there. A fourteen-year-old who has just seen a Brando movie and is walking around trying to carry off that image. But it’s real clear, the disparity. The way I can tell is the position of the legs. They don’t really look like they’re firmly placed on the ground. Sort of from the chest up, I look tough and arrogant, although it’s real hard to see my face in this. But even in the face, there’s an arrogance to it. In the tilt of the head and the sway back of the shoulders, and the leaning against the wall. But again, this is more for Neil. Neil made me conscious of clothes. When I first met him, I used to wear loose jeans and sweatshirts. And he made me aware of the fact that clothes can be very sexual and can reveal one’s body. I guess part of the reason I wore loose clothes was that I was not aware of my body at all. We were shopping and Neil liked this cap and thought I should buy it. [Photo 11]

I liked it abstractly, but I didn’t know if I would like it on me. I thought it was a nice cap as caps go, you know, but . . . I didn’t think it was my image . . . at all. And although I sort of liked the way it looks on me, I realized it’s not me and I was uncomfortable wearing it because I knew when I took it off it fucked up my hair and that was somehow more important to me than what the cap looked like when I was wearing it. But I thought Neil wanted me to look like this. Neil loves that image. And that couldn’t be further from who I am. I mean it’s just . . . it’s who I am when I feel real defensive. I know what I feel like when I do that. I don’t like this picture, you know. I don’t think it looks like me at all. At all.

Why?

I would not be attracted to that person. My criteria may be somewhat suspect, to be sure. However, I know I wouldn’t be attracted to this person. Uh … I don’t know. I mean I guess this is like…My feelings about these pictures with the cap basically have to do with the fact that Neil wanted me to look like this more than I wanted to look like this. Neil gave me lots of validation, like when I would wear a leather jacket. He loved the image. And I wore it more for him than for me. And I sort of felt trapped by that, too, because I wanted to attract him and wanted to keep him interested and wanted to satisfy him. His image of me. And I guess I resented that…It’s called loss of identity, loss of autonomy, loss of self. That’s how I see this picture now; that’s how I would sum it up. A real manifestation of my loss of self—in the relationship.

Did you and Neil talk about what you looked like?

Yes. Yes. Neil said I was beautiful. He was always telling me how beautiful I was. He could never understand why I didn’t see it. And I honestly didn’t see it. I didn’t feel sexual, I didn’t feel beautiful. I felt like I was, um, reasonably good-looking, relatively speaking. But Neil really lauded my looks . . . he lauded them. Another reason I never quite trusted him is that I believed he thought I was good-looking, but that wasn’t what was important to me. It was important that I was sexual. I mean, fuck being aesthetically pretty or good-looking. I wanted to be sexual. Neil doesn’t have clean good looks, but he’s very very sexual. That was what was more important. I just felt Neil one more sexual because I was real attracted to him and he didn’t seem so attracted to me. It later comes out that one of the reasons he didn’t have sex with me as much as I wanted was that he felt threatened—I seemed insatiable sexually. And I also used to do this number . . . we would have great sex and I would rhapsodize right after it: oh how terrific that was, and scream and yell at the climax and it was like real heated and real exciting, but the next morning give him a list of what was wrong with it. It was very fucked-up of me. He only picked up on what I found wrong with it; he didn’t pick up on what I had displayed the night before . . . how wonderful it was. Or he didn’t understand the change, the immediate change. And understandably. I resented the fact that I enjoyed it so much, so the next morning I would indict him for it, for all the things he didn’t do absolutely perfectly . . . like not touching me a certain way I wanted to be touched or something.

Let’s go on to Photo 12.

This was taken about two months before Neil and I went to France for the summer. I wanted Neil to take a passport photo. I was feeling real shitty that day; it was hot and muggy, I guess in May, and nothing was going right. I remember that whole day. I was real bored. And I decided I might as well do this ’cause we had to do it. So we were walking around SoHo, right near our house, and I wasn’t satisfied with any of the backgrounds. I didn’t want a brick wall and I didn’t want graffiti on the wall and I didn’t want a parking lot and I didn’t like anywhere. I was being real bitchy, real spoiled. Like a spoiled little brat. And Neil was getting frustrated. He just wanted to do it and get it over with. And there was no way I could find the right spot. We used up half a roll. This is one of them. He was saying “Come on, let’s just do it.” And I was really getting furious, I mean really furious. I also know the anger had very little to do with that immediate situation. It had to do with other things, which I don’t remember at this point. Probably that we didn’t have sex or something, or he had sex with someone else, or God knows what, but that was usually why I was angry throughout the relationship.

I have a theory related to this picture, about love. Neil and my mother are the only two people in the world I ever really get furious at. And I used to get furious at Neil a lot . . . really vicious, vituperative, bitter, screaming, yelling, really putting in the dagger. I can only do that with him and my mother. This picture was one such occasion. I can see the fury in my face. Real hatred. I mean there’s hatred there. And one thing Neil could never understand is that my anger was a sign of really strong feelings for him, I mean incredibly strong feelings. He could never understand that anybody who loved anyone else could get angry at them. And I have this theory: to love someone means to feel as many different kinds of feelings as strongly as possible for that person. The full range of feelings. Which includes love, incredible need to share, resentment, anger, tenderness, bitterness. I mean everything, the full gamut. I still believe this is so.

To love Neil wasn’t just loving; it wasn’t just sweetness and light and springtime and flowers. It was also real anger and real resentment and real jealousy and real bitterness. And real tenderness and real sharing and real caring and real loving. But he never understood that. He never accepted that. He never wanted to deal with that. He couldn’t understand why I would get so angry with him. And he thought it was an act of hatred or dislike of him rather than a manifestation of the fact that I cared as much as I did.

You think Neil thought that love was some sort of benevolent, warm feeling.

Yeah. Right. Love was the fairy-tale versions of love . . . going off and living happily ever after. He didn’t understand where the anger fit in. I think he started to, later on in the relationship, toward the end. It was very difficult for him to deal with my anger. I can understand that.

When I would exercise anger he would feel it was a betrayal of my love for him, rather than seeing it as part of my love for him. He also couldn’t get angry at me and wouldn’t get angry at me, and that would make me angry too. I saw that as an indication that he didn’t really love me. For Neil, showing love was doing things for me: making dinner for me, going shopping for me, buying me things.

And for you?

For me, it was . . . being with him, holding him, talking to him, expressing it, talking about it. Also doing things. Like I started feeling really oppressed by the fact that Neil was able to do a lot of things. He was able to fix dinner; he was able to go shopping. He wrote at home. He didn’t have a nine-to-five job. I did. So it was harder for me to do those kinds of things for him. And also out of anger or resentment at the fact that it was his way of showing me love, I would withhold just those things from him. And it was a real game. I realize more and more that it was a real game-playing kind of relationship. We did a lot of dances around each other. Like withholding a lot. Neil also, since he withheld sexually, I withheld in other ways. For me a really strong manifestation of love was to make love with him. But to Neil a strong manifestation was doing things, keeping the apartment clean, shopping, making dinner, things like that. He withheld from me sexually, I withheld in other ways. I wouldn’t make dinner, I wouldn’t go shopping. Things like that. It was a very clear tit for tat. As long as he’s gonna withhold sexually, I’m gonna withhold from my responsibilities in other areas.

Another thing, in terms of anger, just as an example: we went to a party once in a giant loft not far from the house. And we had had sex just before we went to the party, at my instigation. I was almost begging him for it for over an hour. And finally we had sex. Neil wasn’t into having sex; he was too exhausted, this was his excuse. Then we went to this party, and about an hour into the party he was off somewhere and I was talking to some guy who’s coming on to me. All of a sudden Neil comes up to me and says, “There’s this guy over there, he’s like real hysterical, real hyper, he keeps coming on to me; I don’t know what to do.” And I said, “What do you want me to do, Neil?” He said, “I don’t know, I mean what should I do?” And he pointed the guy out to me. And I said “Um . . . it’s real clear you want to go with him.” And he said, “Yeah, but how do you feel about that?” And I said “Do whatever you want.” I was furious. And so Neil left with this guy. And I freaked; I mean talk about anger, talk about despising somebody. I mean there was an active despising, hating, such fury. I wanted to kill him. I literally wanted to murder him. I had this fantasy. I left the party about five minutes after, hysterical—

Alone?

Alone. I walked the streets till three in the morning and I met somebody and it was the first night I ever slept out of the house all night. It turns out he made it with this guy in a car in about ten minutes and he went straight home. And I didn’t come home all night, I was so furious. But I had all these murder fantasies. Fantasies of killing him off. I’d like to murder him, I’d like to beat the shit out of him, I’d take a gun and shoot him too.

I really wanted to murder him. It was an ultimate betrayal. And the thing is, I was in a CR group at the time; the next day I went to the CR group and I was really still hysterical. And I told them the story and everybody said, “Why didn’t you say you didn’t want him to go?” I mean it’s the clearest thing. And—um—it never occurred to me. One of the reasons Neil did it was because I gave him this option to do it. I mean I said, “Do you want to go?” rather than saying, “Neil, I don’t want you to do it.” But I couldn’t come out with “Neil, I don’t want you to do it.”

I expected Neil to know what was going on with me. But when I didn’t know what was going on with him, I would use the fact that it’s his responsibility to tell me. I would say, “Neil, I can’t read your mind, you’ve got to tell me what’s going on.” But I would expect him to be able to read my mind.

You two were in separate CR groups and you didn’t have friends in common before you met, but traveled in independent circles. How did that work once you got together?

I didn’t see all of my old friends. I think each of us started seeing fewer of our previous friends. But there were a few on both sides we saw consistently throughout the relationship. They were privy to all of the ups and downs and crises, and knew the daily moods of our relationship.

Were they drawn from both Neil’s friends and your friends?

Yeah, I would say so.

How did you socialize with your friends? Did you have dinner parties, did you meet them in gay bars?

Well, we both had straight friends. My two closest friends from before meeting Neil became Neil’s and my close friends. They’re married and have three children. I also had a very good friend from work, Susan. We’d have dinner either at their house or at our house, we’d go to movies together, or we’d go to concerts, or we’d all go dancing, late at night after a quiet dinner at our house or something like that. That’s pretty much how we socialized with them.

How often?

Usually about twice a week, I would say, the two of us together. Neil also had his friends and I had my friends and we would spend separate evenings with them. He would go have dinner with a friend of his and I would go to a movie with a friend of mine.

But you never became one of these couples who were totally inseparable—you can’t see one without seeing the other?

No, no. I would spend evenings with Susan alone over dinner, and then she would come to dinner at our house with the both of us. No, we didn’t have to be seen together at all times. We were somewhat independent that way. I still felt jealousy when Neil went off with his friends, who were primarily gay—some of my friends were gay and some were not. Umm . . . most of Neil’s friends were gay. And so I would feel a threat when he went off with his friends. And, in fact, I would go off with friends in order to compensate for my jealousy. I couldn’t stay home and read while Neil went out—I would have to go out. We often didn’t meet our friends in gay contexts, I guess. We would do other things with them. Although Neil and I were both very involved in a number of gay organizations and would go to their meetings, usually once or twice a week. You know these organizations, Gay Academic Union, Gay Activist Alliance, Gay Media Coalition—and out of these groups we did form a few friendships. And so we did meet in gay contexts . . . you know, after meetings we’d have coffee or a drink or something like that.

Do you think these friends provided you with any social validation as a couple?

The gay friends did, certainly, in that we were pretty much the only couple they knew [laughter] . . . or if not, the only couple they knew that lasted as long as we did, which was not all that long. But we seemed to have a permanent relationship, we had a home together, we shared our lives together, we were clearly very much involved with each other—and our friends set us up in the sense that we felt—like when I was going to move out, we felt like we were letting our small gay community down. The paragon was crumbling.

Did any of your friends not like Neil, or any of his friends not like you?

I think more of my friends didn’t like Neil than Neil’s friends didn’t like me.

Was that a problem?

Yes, there was a problem . . . in that mostly I would deny that to Neil. It was certainly not a problem so much that they would not see me if Neil was there. They would see Neil. Most of my friends liked him though, or got along with him. We also used to use our friends a lot as sounding boards for our relationship and we would hold court with our friends as the jury, each of us giving our testimony about any particular incident during the week or the day before, rallying our friends’ approval, so one of us could say to the other, “See, I told you so. See, I’m right.” We spent a lot of time doing that at the expense of our friends and their needs and their desires. I think that was a mistake.

Do you think the validation you got as a couple from your friends was important to the relationship, as a sort of substitute for the lack of social validation?

Yeah, I do. I didn’t get it from my parents and I didn’t get it from people in my office. For example, my office held an annual picnic twice a year to which spouses were invited to come. The first two picnics I couldn’t bring Neil, or I didn’t know if I could bring Neil, so I didn’t. I didn’t feel the social sanction there, whereas our friends saw us as a couple very clearly. You know, somehow that served as an adherent for how we thought about ourselves. They provided support for the structure that we were trying to create for ourselves as a couple.

How about the gay world in general? Did that offer the same type of support? How did you relate to it? Did you go to bars?

No, we didn’t go to bars together. I refused to go to bars with Neil; I refused to go cruising with Neil on the street. I didn’t even like walking up Christopher Street with him. If we saw a film and we were walking home and Neil wanted to take a walk through the Village, I would not go with him. The gay world presented too much of a threat to our relationship, I felt—other than the political groups, where the people were related to each other not so much sexually but in theory and in analyses of the gay world, which was safer for me—the real gay world presented a sexual threat.

The gay world didn’t seem very hospitable to a couple?

Right, absolutely.

I presume you never went to the baths together.

No, never. We went separately.

Fire Island?

Never.

Provincetown?

Provincetown we went to together, but we were staying in our straight friends’ house, so it was a family situation.

That’s very interesting; insofar as you were involved in the world, for instance at Time-Life, you weren’t being seen as a couple. And the gay world made no room for you as a couple.

It could have, but I was too frightened. I mean I think the gay world exists in a way where couples do make themselves known as couples, and will cruise together and pick people up to take them home and they remain a couple and have threesomes. I simply never felt comfortable with that. I never felt comfortable as a couple in a sexual context. And gay contexts are primarily sexual contexts. Other than political groups.

Do you really think the gay context is primarily sexual?

Yes I do.

You don’t think there is a certain society?

There is a certain society—it’s a highly decadent society. The reason Fire Island exists, for instance, is because of the sexual operative which exists within that society, within that professional, upwardly mobile society of gay men. Well, yes, there are other interests than sexual interests, but if sex weren’t there or if sex weren’t presented the way it is, then it would not be a gay context. It would not be a gay community.

Fire Island Pines is a very beautiful place, a very nice environment, but gay people have congregated there because there exists a sexual operative. They have also created the sexual operative because of the fact that they are a gay community. I don’t know how to explain it. You can take anything which is stereotypically a gay interest—the opera, the theater. Gay people can come together in those contexts. They can meet at the opera, a museum opening, but they’re not going to talk about sex. They won’t overtly come on to each other sexually because of the context, the nature of that context is not gay. It is simply a cultural context.

The ballet world, the opera world, they’re not predominantly gay; there are many, many gay people in those worlds, to be sure, but the principles of those worlds, if you look at them, are very heterosexually defined. Look at the opera; look at the ballet; they always deal with the man and the woman. Even the parties that they attend afterwards. Although everybody acknowledges the fact that eighty percent of the people there may be gay, you certainly couldn’t see it from being an outsider looking at that party. It would look like any cocktail party in Westchester.

You’re saying that the gay world, the gay culture insofar as it exists as a reality, is predominately a sexual creation.

Yes.

That is, its base is principally sexual?

Yes.

Interesting.

When Neil and I went to the opera or to a museum opening, or a straight cocktail party, I didn’t feel threatened at all. In fact, I felt less threatened in those contexts than I felt as a couple in the gay community, because there was no basic threat to our relationship in those contexts. If anything we were real allies in those contexts.

Do you think that your perception of this is colored by the fact that you live in New York?

That may be true; I really don’t know. It makes sense that it may just be in New York City, in that in New York City people find friends and discover their own milieu in terms of their own interests rather than their sexual proclivities, because there’s always that availability later on in the evening of going out in pursuit of the satisfaction of your sexual needs, whereas in smaller towns all gay people have is each other because there aren’t that many of them. And it turns out that gay people share interests in smaller communities.

Go on to the next photos?

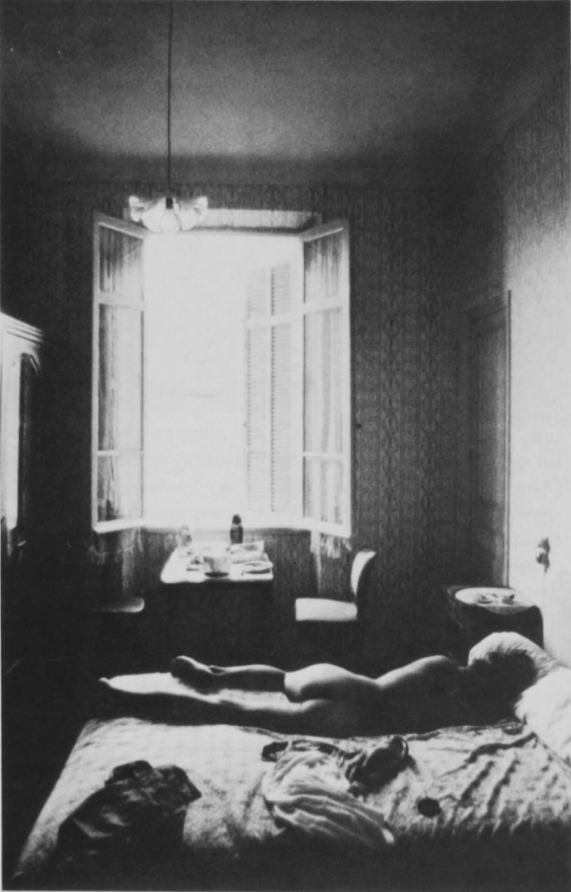

These [Photos 13 and 14] were taken in Cannes. Neil and I had spent a month driving through France. We rented a car and camped out half the time, which got to be awfully uncomfortable. We realized we were much more bourgeois than we had ever considered. We went to Cannes for a week. I mean it was a lovely week. We had this lovely hotel, very cheap, breakfast in bed, and we’d wake up at eight o’clock and have croissants and coffee and drive to the beach, spend the whole day at the beach right outside of Cannes. It was a gay beach, it was a nude beach, it was not very crowded, and we just had this lovely day, every day, hanging out on the beach, reading and drawing and playing Scrabble with each other and talking, and each of us going off and cruising and we’d get off with people, and we never where neither of us could see the other. For some reason Cannes was the only place and the only time throughout our whole relationship that I was not really jealous. And at night, I think two or three different nights, we went separately with other people and had sex with them, and it was really fine. And I don’t know why.

Did you have sex with each other?

Yeah, we had sex with each other. And that was good.

And you were being very successful when you went out by yourself?

Yes, absolutely. In fact at one point, I met this one guy, Bob, who lived in Cannes. And I was walking on the promenade with him and ran into Neil. And Neil saw this guy I was with and said, “He’s gorgeous, I mean like I’m jealous but I can’t not let you go home with him, he’s so beautiful.” And so Neil left so I could go home with this guy because he thought, like wow, what a conquest. And I would never do that. I mean I know if I saw Neil with somebody who was that beautiful, I would freak out.

Even at this time?

Well, at this time, I don’t know if I would have as threatened as I had been in the past, but I don’t know if I could have been as gracious about it as Neil was. I was amazed at Neil’s graciousness. But that was pretty much the way it was at Cannes: I mean it was just idyllic, lovely. And for me that week was the honeymoon. Two years after the fact. It was like the honeymoon.

What about picture 13?

To me, this picture is Neil. It’s a very private moment of Neil for me. We’ve just come back from the beach and I’m about to take a nap and Neil is already taking his nap. The two of us in this hotel room. It’s a very intimate moment. I mean Neil is totally vulnerable; he’s asleep, his back . . . like I’m behind him. His little tush is there. I mean he’s very vulnerable. There’s a part of this picture which is the three-year-old Neil, which I talked about before. Like he’s mine. He’s mine. Like we take care of each other. He can be vulnerable, he can lie there naked, asleep, with his back to me, in this most beautiful little room with late afternoon light.

In terms of this picture of me [Photo 14], I was seeing myself as looking very French. And I was very successful in France. I was a real hit, and I started seeing myself that way. Or feeling that way about myself. I took this picture, and you can see the difference, I think, between most of the pictures Neil took of me and this picture I took of myself.

My face looks totally different. My hair was also longer. I was also very tanned. And I felt real good about the way I looked. I was just playing in front of a mirror. I loved what I looked like. I also don’t think I really look like this, but I guess there are times when I feel I do project this, this image, which is very French.

Whose idea was it to go to France?

Mine. I definitely wanted to take a full month’s vacation, and I didn’t do that the year before. And I decided I wanted to go to France and drive around the countryside. It was going to be my great romantic vacation. But my initial decision to go to France hadn’t included Neil. I was going to go to France whether Neil went or not. We didn’t know if Neil could afford it, and then we started talking about going together. So it was totally my initiation.