This article originally appeared in the February 1978 issue of Christopher Street, on pages 17-28.

Previously in this series: Michael Denneny's introduction and interview with Philip.

NEIL ALAN MARKS: I met Philip in a writing class at the New School. He had long golden hair and one of those eternal-looking suntans that never goes away. I had just ended a very dreadful month-long affair with somebody and I wasn’t looking for a relationship. I’d been in Europe for six months and just gotten back and took a writing course to get in touch with my writing again and I saw Philip sitting four rows in front of me. Quite honestly I didn’t think he was gay. I kept saying to myself, “even if he’s not straight, he’s real young, Neil.” Because he was twenty-one at the time and I was what, twenty-four?

And I started talking to him and a couple of weeks later I asked him to have coffee at this raunchy coffee shop down on Christopher Street. We talked and talked and I asked him if he was gay finally, and he said he was bisexual or something. He was involved with this very beautiful woman. I was obsessed with him. He had a really classical face. I’m usually turned on to people with something slightly wrong with their faces. Not drastically, but just something that I find very primitive, almost. And he wasn’t primitive, he was anything but.

So I started trying to date him and he came over one night and I pounced on him. And he was really stand-offish. I thought he was real cool, by the way, a real cool guy, laid back, Southern like. He wasn’t being direct. He was being evasive about all his answers. Which was a nice change for me because I’m usually involved with very frenetic people, and I’m usually only attracted to very intense people, but in this case it seemed different. He was Jewish, but he wasn’t New York Jewish.

Anyway, we tried to fuck, but I was tight and somehow it just wasn’t working. I don’t know why. All right, that’s life. You know, you win a few, lose a few. And he left. I was very depressed, and what does a depressed writer do? He writes a short story about what just happened. Ironically, two weeks later both Philip and I were picked to read our pieces in class. Philip had written a piece about his ex-girlfriend or something and I had written a piece about Philip, which was very graphic and which freaked the whole class out.

MICHAEL DENNENY: What was the impact on Philip of hearing the story?

I think he was mesmerized. I don’t know at this point what his real reaction was. His piece didn’t work, the teacher told him; and mine did, very obviously. Knowing him as I do now, I think he might have felt a lot of competition. On the other hand, I felt it was only right since I was older. I’d written a novel already, so it wasn’t as if I was a total novice at writing.

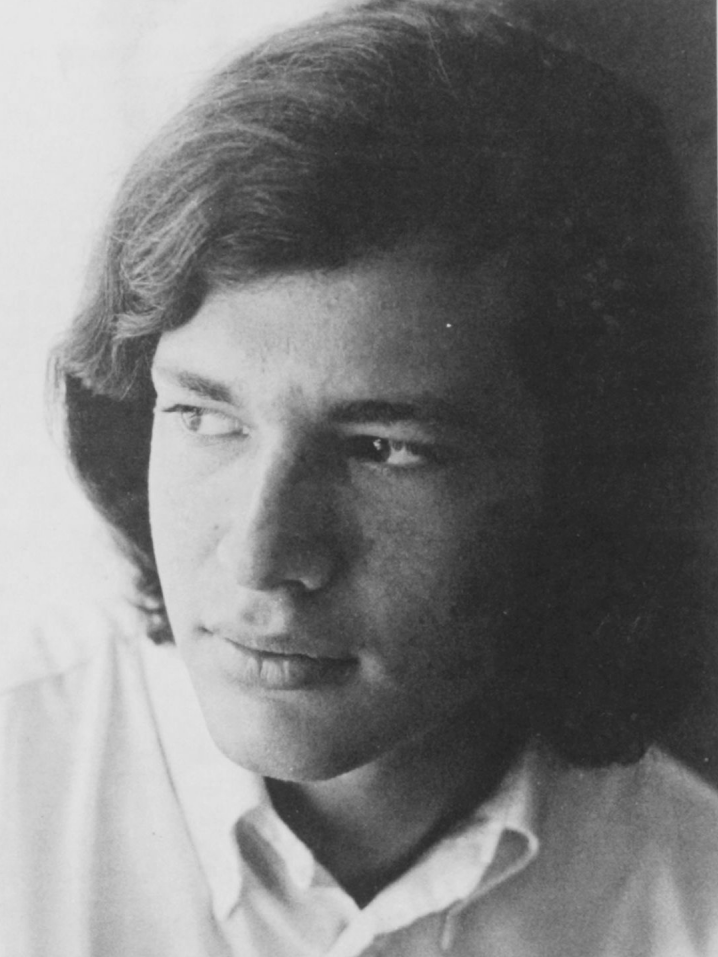

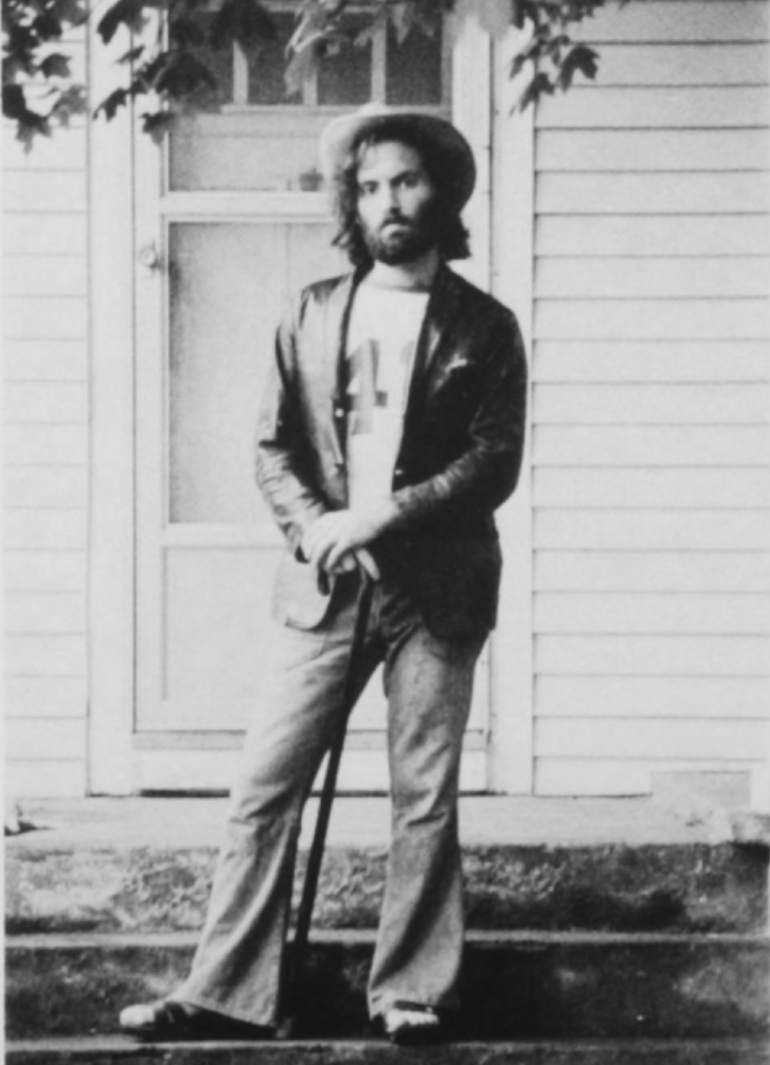

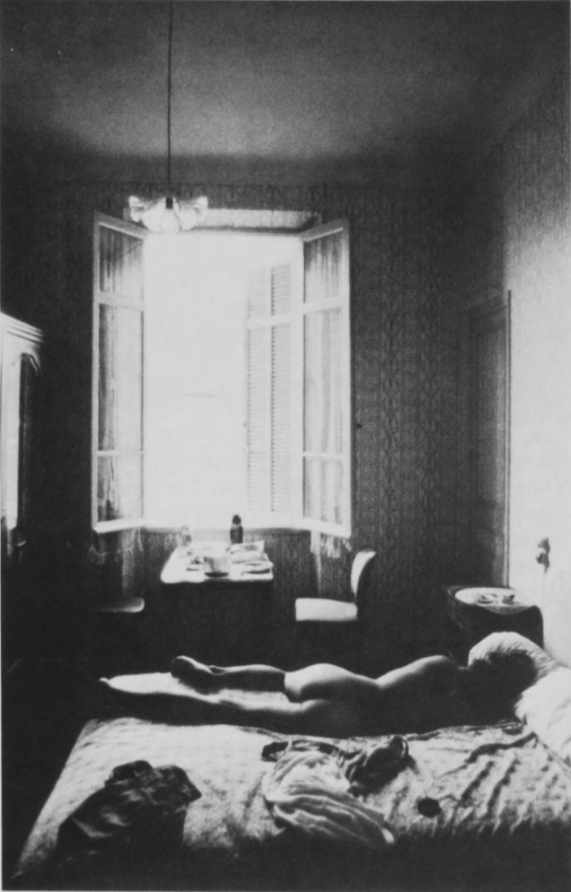

In the second photo [Photo 2], Philip had just gotten out of school. I think he had to get a job, so he had all his hair cut off and that’s what he looked like. He dragged me to all these barber shops, and I pay three dollars for haircuts. I don’t approve of spending fifteen or twenty dollars. That’s when I started getting very suspicious of Philip. I was falling in love with him, but as I was falling in love with him, I was seeing all these things I didn’t like. He had an almost lethal attraction to sophistication, and he holds me responsible for that because in the beginning I kept telling him he had all this ratty clothing. I told him if you’re into sex in life, you should dress like you’re into sex, and he did a turnabout. Then he got this haircut and it was a disaster. He looked like an Upper East Side faggot. I made no bones about it. At the same time I didn’t care.

You told him that you hated the haircut?

No. But I didn’t care. I was falling in love with him. I made it clear it wasn’t the kind of haircut I approved of. But at the same time I told him that it really didn’t matter. That he was so beautiful he could get away with it. He’s one of those people that gets away with anything. He really gets away with it.

But the big climax of that whole time was when his friends, Terry and Sally, gave a party. They were very key people in his life, sort of the nice mother and father figure. I think Philip was in love with Terry. Not surprisingly, I looked something like Terry; I had the same Jewish motherly attitude as Terry. Those pieces fell in later after I met Terry. Anyway, they were having this party for Sally’s birthday, and it was the first time I was invited to meet his friends, his family. This girl Sharon was also invited and unbeknownst to me she had dropped three Valium to deal with the situation. I didn’t drop anything. I wasn’t taking any drugs then.

And so I go to this party out in Brooklyn. A real incestuous, lovely kind of setup. Everybody’s real close and real warm to each other. My family is real close, but I don’t have too many friends. I just don’t. Now that I do the radio show I know a whole lot of people but I don’t have many friends, you see. And it’s a real lonely life for me. But that’s life. So I really liked the idea of getting into this family. And then Sharon walked in and Sharon was dazzling. She was the most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen in my life. She had a pristine face, perfect hair, this long, long—I don’t know, what was it, gold or brown or something beautiful—and she had these dazzling eyes, a svelte figure, and she and Philip were a perfect couple. And I was beginning to feel guilty. I was destroying this perfect couple. I was doing my darndest to destroy this perfect couple. I saw them dance together and they were a vision out of Tristan or something, they were just so beautiful together. But in the meanwhile Sharon was freaking out of her mind.

Were you having sex with Philip at this time?

Yes. But it wasn’t all that good. [laughter] We had this big dispute because I hated going out to Brooklyn. He was living near Pratt. And I had this big apartment and this was my fortress, and I was older. He lived in a pseudo-beat apartment, which means a very expensive, sort of Upper-West-Side type of apartment in a brownstone or in a wood frame house or something. I don’t remember it too well. I just remember it was too modern for me and had too many conveniences and I was beginning to distrust him for that.

But I was falling in love and I had to figure out a way to get rid of Sharon. I wasn’t about to share him, and by the time of the party he felt pulled equally in both ways. But I felt I had lost. I was feeling devastated at the party because I felt she had won. She was far more beautiful than I could ever conceive of being and he had been involved with her for over a year, so she had an edge on me. Plus Sally and Terry, everybody there, was making it clear who they favored.

I was getting real freaked out. So I finally dragged Philip into the bathroom and said, “Look, I give up. I’m leaving.” Philip didn’t want me to leave but he was totally freaked out too, out of his mind. So I left and walked to the subway and I kept turning around, hoping he’d follow. It was sad, but that’s life. I get home. I go to sleep. Two in the morning I hear this knocking at the door. I wake up and answer the door. It was Philip. He didn’t leave until two and a half years later, basically.

About a month and a half after that he came and—bang zoom—railroaded me into letting him move in. And I had real doubts about him. He was still cool, but he was getting very pressurey. I was getting a little nervous. He had to really convince me that it was the wise thing. I thought it was the craziest thing I could do. I was against it, but I did it. He moved in and I got physically ill. Physically ill. I was on my back, I couldn’t move for four days. I felt like I was on my death bed. All my friends would come over and sit on the floor next to me and console me. [laughter] I was freaked out of my mind. I was attracted to him because he was everything I wasn’t. He wasn’t earthy. He was sophisticated. He was just everything I wasn’t.

Philip purported to be a real liberated person. I’m real tolerant. I’m like my father. My father certainly doesn’t approve of homosexuality. But he’ll go with the wind. If the wind is sort of pushing you to accept your gay son, you accept your son. I mean, I’m his son, right? And I’m real tolerant of what other people do because I know it’s really none of my business, basically. And as long as I have a sense that they’re really with me they can do what the fuck they please and I don’t care. And Philip seemed to come off the same way. That was cool because I’m real promiscuous. And I was not about to have that curtailed because of love. And also there was another basic problem, and I think it was the most serious problem we had. I didn’t have a primal attraction to Philip. I mean I was in love with Philip but Philip was not my ideal Italian. He was not even Greek. A lot of him was so familial it was frightening.

So what?

Familial. I knew a lot about him before even—we didn’t have to say anything to each other. We had the identical upbringing. We both had a mother who’s a hitter; he had a laid-back father, I had a laid-back father; we had an older brother and sister who were extremely talented and bright. He had that liberal Jewish upbringing which I had—the only difference is everything was expected of him and nothing was expected of me. But other than that, there were just so many familial things which I think bring people very close but are very antierotic. I think I need distance. A certain kind of exotic distance. And as long as Philip was a Southerner, that was real exotic to me. I could cream just listening to a Southern drawl. But once he moved in he became Philip. You know, “Fuck all the other shit. Fuck everything I’m presenting to you, now I’m going to be me.” And what “me” was, was all of a sudden he got freaked out about everything I did.

I mean it was like a hurricane moved in. A little summer storm that turned into a hurricane. And I think the trauma of him moving in caused me to trick out a lot and I started watching television a lot. Obviously trying to avoid something. I also started writing a novel. I went through three drafts before I gave it up. I just couldn’t deal with it anymore.

So Philip moves all his shit in and gets this job at a photography store. Something ludicrous like that. It’s a real wipe-out, boring job. So he would come home and expect me to entertain him. I mean you work at a boring job for eight hours, you come home to your lover, your lover is supposed to sing and dance for you. Do something. But I was working six hours on something I really loved, which was my novel. So I just wanted to relax. I didn’t want to deal with this shit. And here, Philip turned out to be a heavyweight. You know, he wanted to analyze problems. I’m considered someone who’s into analyzing problems in life and I believe it’s real important, but he turned it into an art form—like analyzing the problem took ten times as long as the problem itself would take you. Nevertheless we weathered it.

I’m real stoic in life, and I believe that as long as the good balances out the bad I’m willing to deal with all the shit. I also knew I was rigid. A stranger wouldn’t dream of calling me that but I knew internally I was and that I wasn’t very loose with my feelings. I wasn’t brought up in a family that was loose with its feelings. We’re not physical at all. I’m the only physical one in the family. My father wouldn’t dream of kissing me and my mother would kiss me on the cheek. Her mother before her was half German-Jewish stock and if you know anything about German-Jews, forget feelings. They can’t relate to each other.

I don’t think the sex went too well from the start. I don’t remember. I don’t think I want to remember. Sex was real difficult. I had never, for any extended period of time, fucked with one person four or five times a week. I was going to say one or two but it was four or five times a week, and it was a major achievement for me. It’s interesting, ’cause until he moved in he could have fucked me anytime he wanted. Once he moved in he couldn’t, and a lot of it had to do with my feeling very pressured by him after he had moved in. We would have sex, and he gets more into sex—he gets more into almost anything—than anybody I’ve ever met. I’ll never forget this as long as I live: I would try to listen to music with him, since a big part of my life is music. I mean I was raised on it and I’ve been writing music for about thirteen years. And I cannot play Mahler to this day—I get too upset because of Philip. Because Philip would lie here on the couch and we’d try to listen to music together—I figured we could do that together—but he would listen to Mahler and he was in a world of his own. If you ever go to a discotheque and see all these cute fellows and they’re not dancing with their partners, they’re dancing with themselves, it was like that.

Did your parents know that you were gay when you met Philip?

Oh yeah. Yeah. My being gay has been a very long journey—through being fairly actively bisexual, being exclusively gay, going back to being bisexual, to being exclusively gay. My parents found out in a very negative way—somebody wrote them a letter. Not for money or anything, but just to get back at me, and I don’t even know who wrote the letter. This was back when I was seventeen—not too many people were gay then—and they were absolutely horrified. My father threatened to write me out of the family and the will; he had never mentioned these subjects to me before in my life, so being threatened with being written out was very, very heavy for me. And I had just won a scholarship to study in England, and England had just legalized homosexuality. So my father was having conniptions! [laughs]

We went through this titanic struggle—I went to a shrink, they went to the same shrink the next week, and the three of us went the third week. It was the most frightening experience I ever had, because the analyst accused my father of various things just to get him to react emotionally. He called my father a shit and all these things. I would say, “You can’t call my father a shit”—and my mother breaks into tears: “You can’t call my husband a shit.”

What year was this?

This was ’67. It got real heavy toward the end ... my parents were willing to put me up in an apartment in Manhattan as long as I was going to go straight, and the analyst says it takes at least five or six years to go straight, and I didn’t even want to go straight. So I said I’d rather not do this analysis and I’d rather go to England. So my father pretty much gave up and said, “All right, go to England—I don’t want to deal with this.”

And I left for England, and gay life in England, I mean, it’s hard enough here, but it was really bad there. So on my own I decided, for strictly social reasons, that I wanted to be straight—or at least very actively bisexual—and in fact my shrink turned me into a very active bisexual.

How about Philip and your parents?

Philip and my parents. All right. [pause] He became one of the family. Once I was very clear to myself about being gay, I made it very clear to my parents—you treat me, you treat whom I’m involved with, and I want you to take it seriously. If you won’t take it seriously, forget seeing me. And you don’t argue with this. I was very adamant about that. It was real interesting to me, how the different people in my family reacted to my being openly gay, because empathy came from very surprising places. My mother’s sister, who is a very patrician woman, very refined, was wonderful to me. She was the last person I ever expected to be open about treating Philip as my spouse. I remember the first seder when he was living with me. She always had a seder. And she went out of her way to tell me she hoped that Philip was coming. And this was the first situation when a member of the family, other than my mother and father, knew that Philip was gay. I was really overwhelmed. I appreciated that so much. It was real important to me. Since this was my favorite aunt anyway, she really became a goddess to me. My mother finally admitted that she thought I was crazy. Which was her way of saying she finally saw me as an individual.

She was, she still is, real fond of Philip. She became a mother to Philip, really, because his parents live in Florida. And she and Philip would have these heavy, heavy discussions about sex—about everything. It was real crazy because my parents, every other Sunday or so, would take us out to Chinatown, and Phil and my mother would be in the corner talking about sex or something. My father would be going bananas: “Look at this painting”—and there are some hideous paintings in Chinese restaurants, right?—and he would tell me how beautiful they were. [laughter] Nevertheless my father is my father. He treated Philip like a son really; he was real nice to him and would ask him about my health—things that in-laws ask the kids.

Once my father asked me about my earring. He said at dinner, “Neil, does an earring in your left ear mean you’re gay?” And my mother said, “No, of course it doesn’t. It means that he’s gay and he has a lover. And in the right ear, it means you don’t have a lover.” And I’m just sitting there saying, “Huh. Where did you read that, in Time magazine or someplace crazy like that?”

Philip and my parents got along real well.

What about Philip’s parents?

[laughs] Well, all right. Philip came out to his parents once he was with me. I think usually gays find it’s easier to come out when you have a lover. I mean, I wouldn’t even recommend coming out if you’re alone. When Philip moved in with me he had the strength to come out, really. I was pleased because I was very politically conscious and I was very openly gay, at least relative to a lot of other people.

How did his parents react?

Well, his mother, who is a very, very intelligent, liberal woman, began sounding like a Baptist minister in her letters. It was shocking to me. Really unbelievable, the kind of diatribe she’d write. She called our apartment a den of iniquity, and she called my mother a fag hag [laughs] ... really insane things. It’s that liberals just don’t know how to deal with homosexuality. It just is not in their reality. At all. Since most people have problems about their own sexuality, it’s no wonder there’s so much homophobia. But with his mother in particular, I was the enemy. It was so obvious to me what was going on: it was a battle between me and his mother, and at the same time I wanted so badly that she would accept it. That she would accept me.

Did you ever meet her?

No. But I’ll tell you a funny story. In a way I did. She was coming up to New York—his parents would come up periodically; she’s a name photographer. The Edward Weston show was opening up at MOMA. I had to see this woman. The thing with Philip and his mother was that anytime he had bad problems with his mother he’d take it out on me. So he’d get a letter from his mother or a phone call from his mother and I knew that the next forty-eight hours would be hell. It was like being at the Marne keeping the Germans off or being in Leningrad keeping the Germans off [pause] it’s always Germans, isn’t it? [laughs]. This is how I saw his mother. Every time he would get something from her, he would take it out on me. At first he wouldn’t acknowledge what he was doing—he was in a bad mood, he wouldn’t cook, he wouldn’t do this, he wouldn’t do that, and it went on and on. I had all these fantasies of calling his mother and saying, Look ... where ... the ... hell ... do ... you get ... off, treating him like this and treating me like this. You know, she had threatened to come up and take him out of the apartment—it sounded like one of those deprogramming kinds of situations.

Anyway, she came up with his father to New York to see the Edward Weston show, so I was going to go with Susan—our friend Susan. I was going to pretend I was somebody else. But she’d never seen a picture of me either, so I didn’t have to do that. I stood next to her through the entire exhibit. I stood right next to her; wherever she went, I went. I listened to her speak. And I’d watch her move. I’d watch her every single motion. I knew her backwards and forwards already, but I had to correlate it with the image. I was so dying to say something, to make some strange cracks to her—not as if I was me, just as somebody at the exhibit. That was no go. I really was not interested in his father. His father was like my father, real nice and real sort of laid back. At the end, his father was just about to deal with us, to meet me, at a meal or something, when Philip and I had a final falling out. I wanted to be accepted by his parents. I really did. I met his sister, we got along like that. We both had a very similar orientation, been through the sixties together. I understood a lot about Philip through his sister. Also through his mother—through his mother’s letters and things like that.

But at the same time, I felt a lot better about my parents in contrast to his parents.

Do you remember when you fell in love?

Oh I fell in love with him the minute I saw him. I just melted. I mean I just melted away. He was so beautiful. He really was. He is. He had that eternal look and he had these real sad eyes. And he was really alive. I mean, so many men seem dead already and they were younger than I was. They’re functionally dead. You know, they deaden themselves. They take on lovers and they go through the form of having a lover. Or they go through the form of going to a bar and picking somebody up. Or they go through the form of going to a discotheque. You know, they’re all dead inside basically. Phil was alive. He was really alive. But he was dangerous. Oh is he dangerous. I’ll never forget—I called my friend Paul—and Paul said to me, “You know, Neil, Philip is really beautiful. There is no question about that and he’s really interesting and he’s really bright and blah blah blah, and, Neil, he might be a little too young.” That was the one thing that freaked me out.

I’m not into anybody older or anything like that, but I am hung up on somebody who’s too young. I always was. I like peers basically, because I think peers are emotionally in tune with you. But Philip was young and I knew it. I even knew at the beginning it was going to end. I knew he was going to leave me. I knew this and I kept blocking it. I even said it to him at the start: Philip, I know you’re going to leave me. And of course with that kind of attitude, it’s little wonder it was set up so he’d leave me. So I’m just as responsible as he.

And when he left?

I wasn’t shocked. No, by the time he moved out, so many numbers had been pulled and I was fed up with him and I gave him an ultimatum basically that he either put up or leave. I didn’t say leave. I said either put up or I’m getting involved with somebody else. And I proceeded to get involved with somebody else, but that comes years later.

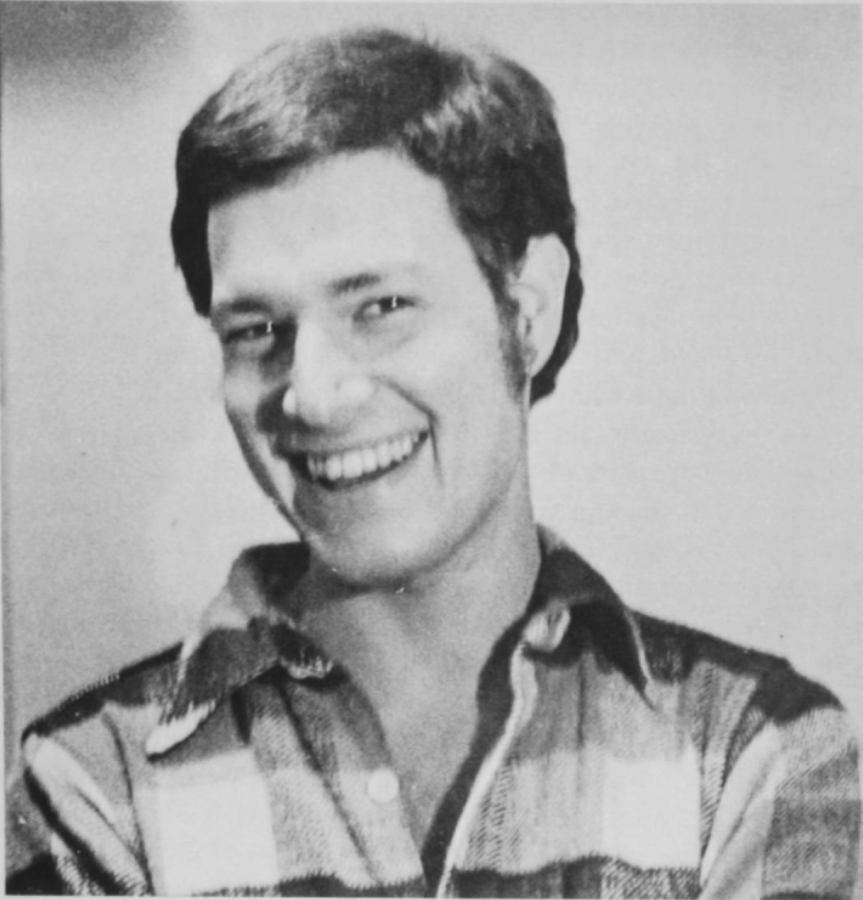

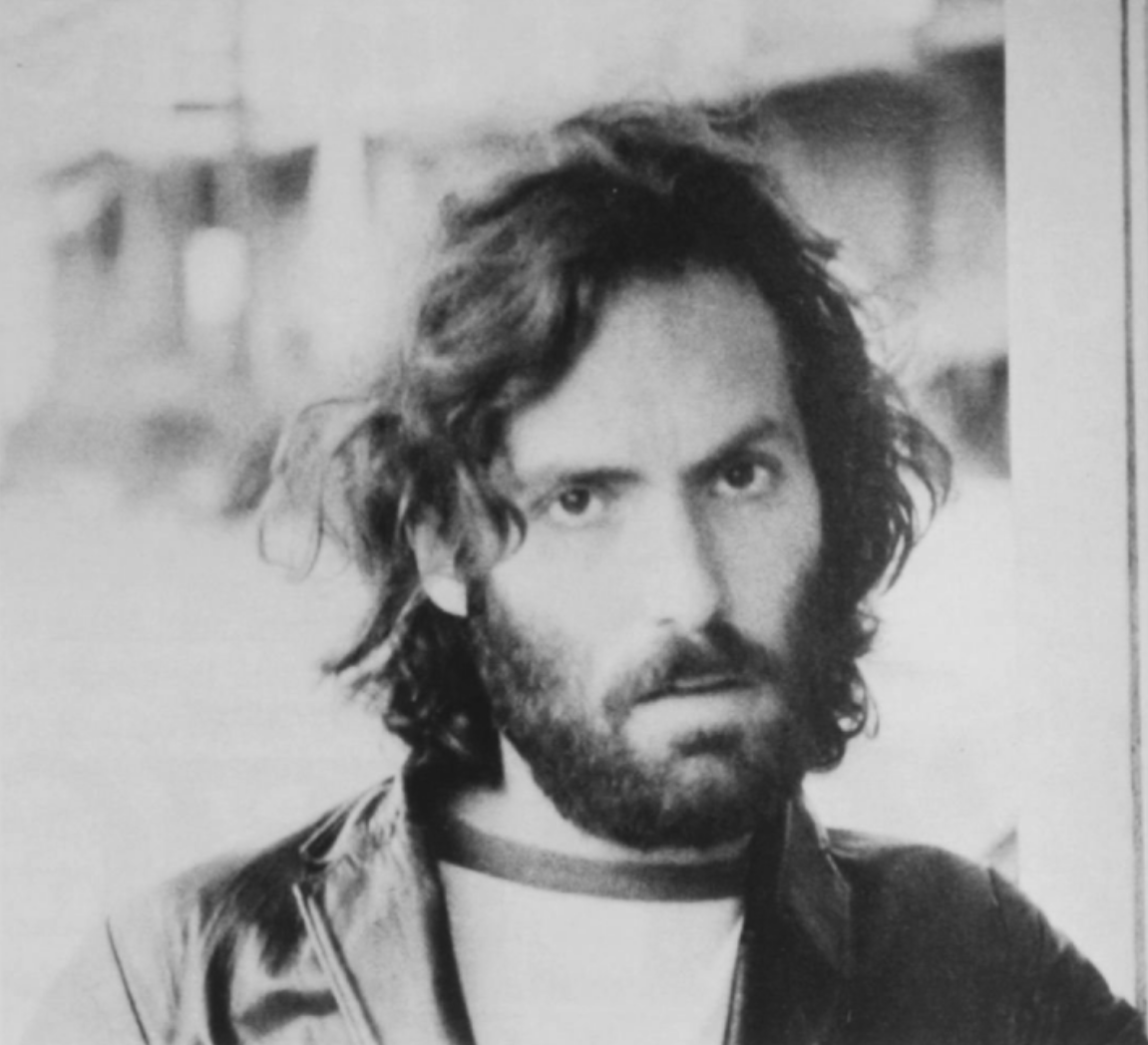

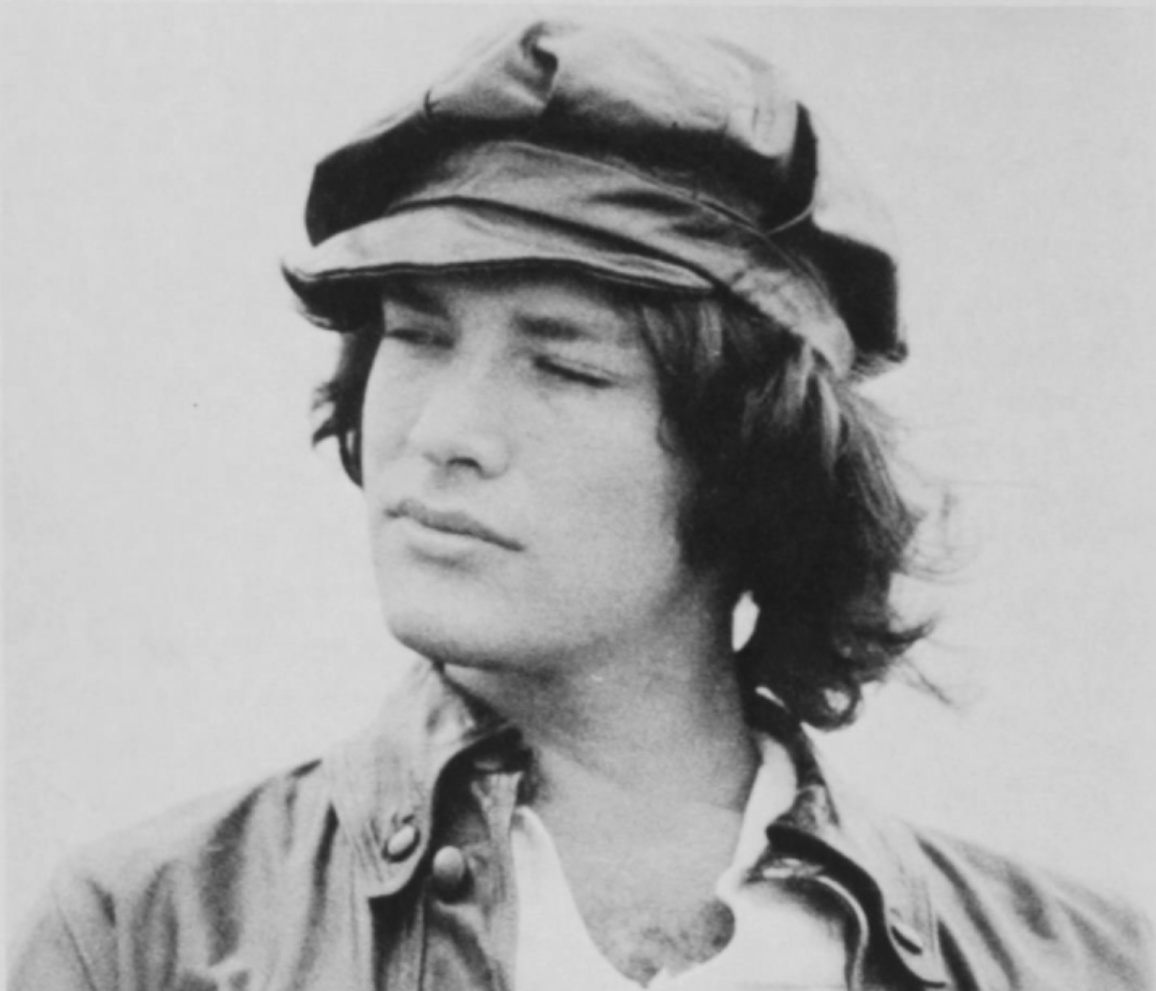

The next one is the early photo of you? [Photo 3]

Oh yeah, that one. I would fall in love with a guy like that. I mean attitude. That’s an attitude photo.

An attitude photo? Hard at work, serious young writer?

[Laughter] Exactly. Exactly the image I wanted, and that’s exactly what he got out of it. That’s exactly what he saw. I was a hold-over from the early sixties, not even the late sixties. I was too late for the late sixties, you know, that whole hippy-dippy trip. In the early sixties, that’s where my consciousness was formed. The whole civil-rights movement, and the whole Dylan thing—that left the strongest impression on me. And in Europe for four years going to school, so I also picked up this certain kind of worldliness. I was real worldly.

Where did you go to school?

England. In England I spoke much better than I do now, real transatlantic English, so they couldn’t tell whether I was a multimillionaire from Boston or a middle-class Jewish boy from Forest Hills.

What do you think attracted Philip to you?

I’ll tell you what he claims to me, that it was my vulnerability. He also claims that I was only vulnerable for a few seconds. I mean the way he talks about me, anybody would fall in love with me. Really. For a few seconds a day I would be vulnerable and he would fall in love. I don’t buy it at all.

Why do you think he did?

What?

Fall in love.

I don’t know. All the things I thought were interesting about me Philip didn’t think were interesting about me; and all the things I didn’t think were interesting about me, Philip fell in love with, so that you know there’s no accounting for taste in this world. Or for love. I guess I was sexy. I came on real strong with him. I worshipped him.

You were sexy but you just said sex wasn’t so good for the first few months.

I was in love with him, I didn’t care. In love you don’t care.

But I’m interested in what you think in reality made him fall in love with you.

There was no reality, there was fantasy. Fantasy. There was no reality. I mean reality, there’s a thin line between what the reality is of how Philip saw me and what the fantasy was.

Yes, but what was motivating him? Do you think it was sex?

No. I was real open in life compared to most people he probably knew . . .

You adored him.

I adored him.

Do you think it was that?

I adored him, I was very straight with him, I told him I was in love with him and he wasn’t used to people being that straight. I remember sitting in a restaurant, oh God, it was over on Macdougal Street, and what did I say to him? I told him I wanted him. You know, I’m real blunt. I just told him I was in love with him and I wanted him. And he couldn’t respond, didn’t know how to respond. He wasn’t in love with me at first. It was very obvious to me. But I also knew that I had my ways, and I would make him fall in love with me. And I did. And I just was myself, that’s all I had to be, ’cause I knew that I was a real attractive property, right? I’ll put it that way. I had all the outside qualifications . . .

Good-looking.

Yeah, I’m pretty good-looking, I’m very good-looking—oh God, that’s a terrible thing to say on tape. All right, I’m good-looking, just leave it good-looking. I have style. I don’t think I’m ordinary. I’m not your run-of-the-mill faggot, I guess. I have solid credentials in terms of involvement, you know, like political involvement. Solid left credentials. Philip’s sister has solid left credentials, he was brought up that way too. So we had a very common world view. And I also had this European view. ’Cause I had traveled in Russia, I had traveled in India, I had traveled all over. I was obsessed with travel. We Sagittarians all are.

You think that was important for why he fell in love with you?

He was overwhelmed with it. I would be too, you know? Like when I meet a concert violinist, oh, I’m in love with him immediately, just like that. I think people get overwhelmed with credentials. I went to the London School of Economics, I spoke French fluently, I was nice. Not now, but I was nice. I don’t know why he fell in love with me. I’m giving you all the reasons why he might have.

I was just curious what you think. You’ll be curious when you read what he thinks.

I don’t believe that. You see, I don’t believe he’s honest that way. I don’t think he likes to ascribe superficial motives to himself. There have to be these real profound motives, and I don’t think human beings are made up that way. I think we’re made up of profound and very superficial motives in everything we do. I think I’m a very secure person to be involved with. I think he knew that. I’m real solid. I’m not flighty. Again I’m falling apart now, but I’m not generally flighty.

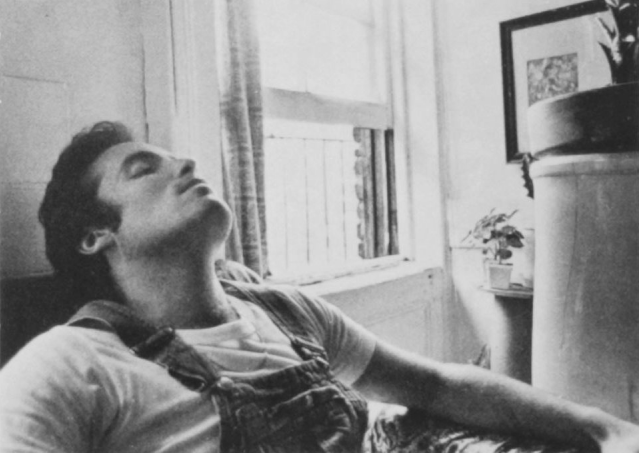

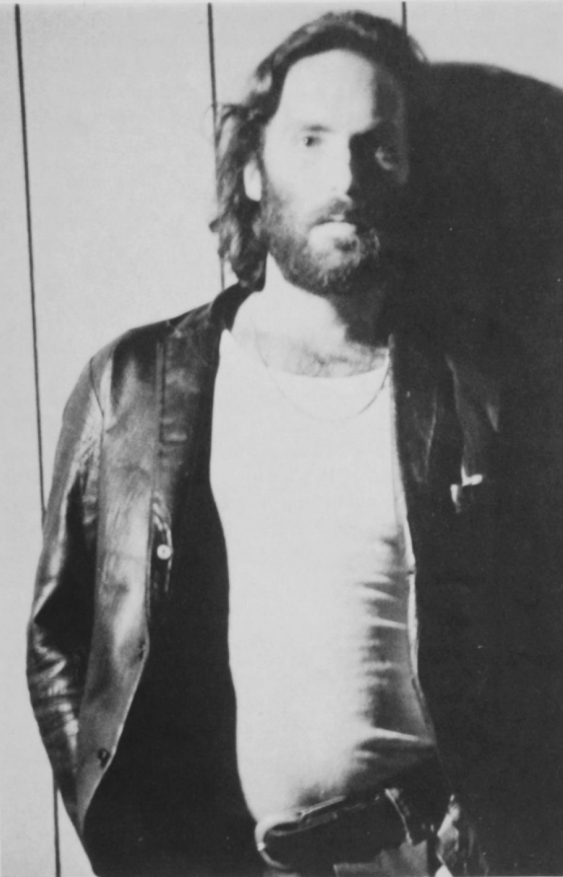

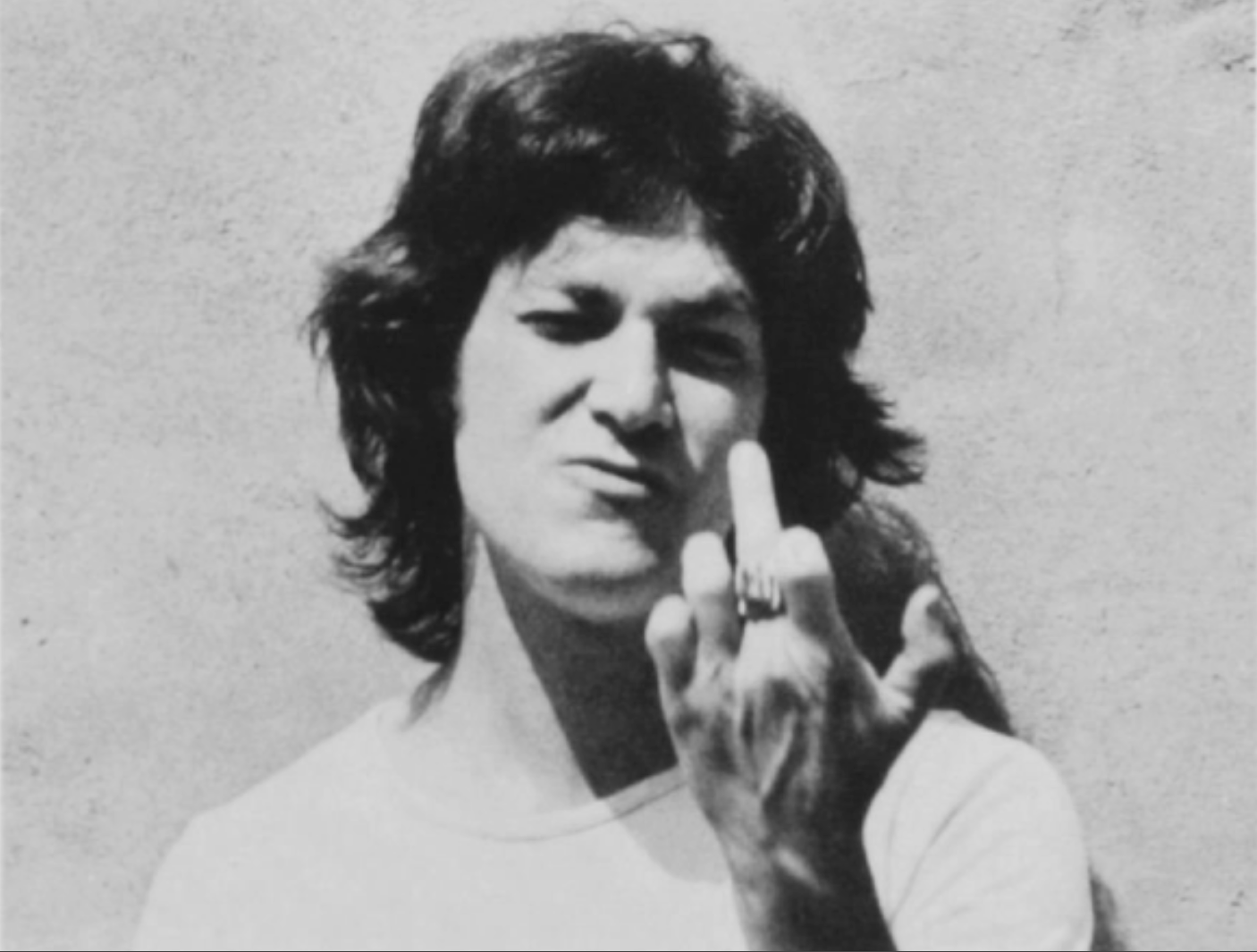

Photograph 4.

Me in the steam. I think Genet was the first person who opened my eyes to the night side, the life that goes on between midnight and dawn. And part of me is obsessed with the Satanic. Like S&M, I’m not into S&M particularly, but I was curious. But I never did it with Philip; I had him on a pedestal. And so whatever might happen in my “fantasy life,” with Philip it was all romance. It was like a nineteenth-century full-blooded romance. He was right out of Botticelli. That’s the only fantasy I had with him really. Botticelli.

This photo is the side of me which Philip felt real ambivalent about. This is the demonic image. The look, the attitude, the demonic attitude, which I can pull off real well. It’s like sweat. Have you ever met people who say they don’t like sweat? Well if somebody ever said that to me, I’d throw them out of bed on the spot, not because I’m obsessed with sweat, but anybody who’d actually delineate the fact that they don’t like sweat belongs out in Scarsdale, sleeping in separate bedrooms, really.

I’ve always seen myself on the fringe, and I’ve always related to the fringe writers like Rimbaud, and I told Philip to take that picture, ’cause that’s how I saw myself really.

Moving right along ... did you have more to say?

Oh I could talk for hours about myself.

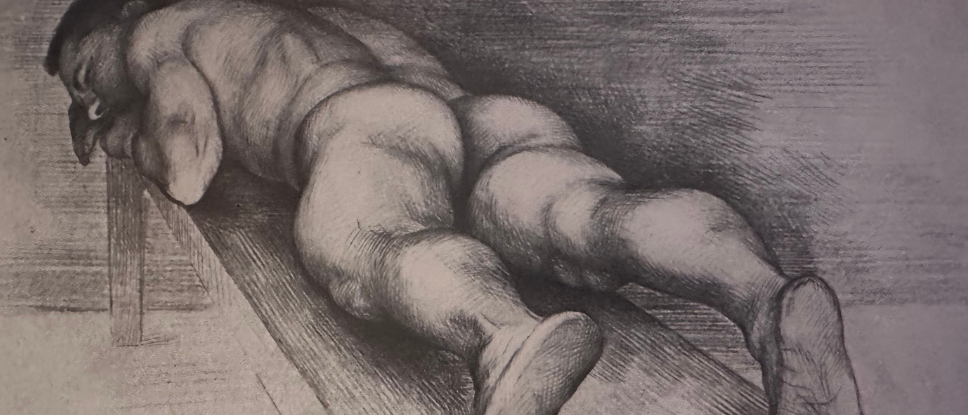

Photo 5—Philip as St. Sebastian.

No. It’s not Philip as St. Sebastian. That’s not St. Sebastian! It’s Botticelli! The Botticelli David. [very long pause]

OK. Would you rather talk about Photo 6?

It shows all my ambivalence and all my anger and all my hurt rolled into one. And it just so happens that I had just got out of the hospital. I was run over on Canal Street and knocked up in the air and down on my head and I had twenty stitches in my head, and my leg was banged up. Now I expected a lot of sympathy when I got out of the hospital. I got to Provincetown and people were treating me as if it was just good old Neil. And here I was having three migraines a day, I was just not in good shape. And I expected to be treated with all due respect.

How did Philip treat you?

[Pause] Philip was petrified. There was a lot of love there, but I just felt that he was treating me like one of Laura’s things in her Glass Menagerie. Like anytime I moved I was gonna break something. He was like almost crying every time I walked. He was always afraid I would knock my head against something. He would almost break into tears.

He was scared?

Yeah. He was real scared. And like he really took care of me, I have to say, he really took care of me. He really thought I was going to die.

What do you think this photo shows about you?

Oh, my sense of eternity. Just eternal longing for something, you know, I’m always longing for some sort of happiness. But to get it, God, the hell you have to go through for a little happiness. You know, it’s like artichokes. Like all there is to the artichoke is the choke basically, and yet you have to go through all this, it’s really heavy when you buy it, and then you suck off the leaves and get to the choke and there’s barely anything at the choke. And it’s like what you have to go through in life; for a little happiness you have to go through so much, so many hours and months of shit ... I remember this guy I was living with in Paris for a while. Said I had the saddest eyes he ever saw in his life. Maybe that’s what this photo shows: the saddest eyes I’ve ever seen in my life. Isn’t that pathetic?

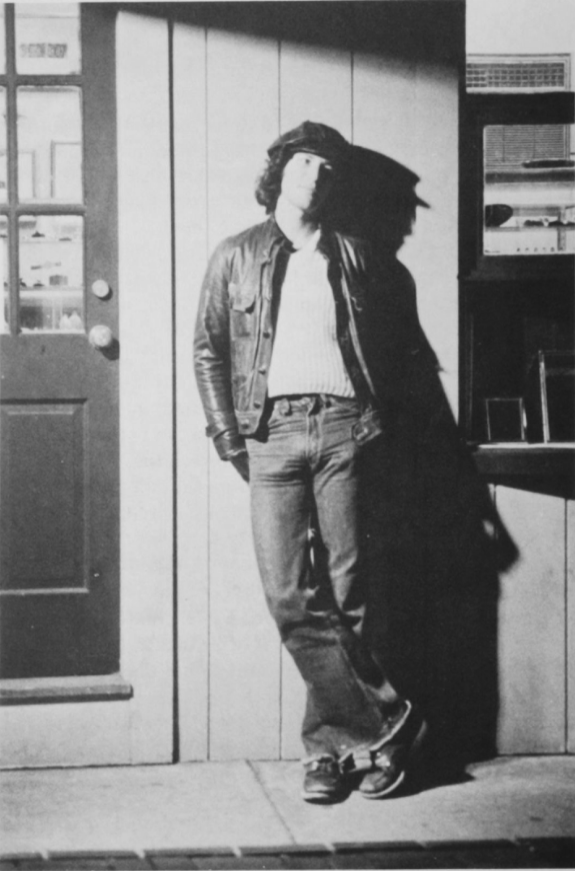

Look at Photo 7.

That’s Neil the iconoclast. ’Cause Neil’s wearing a football shirt and a black leather sports jacket, and his cane (’cause my leg is messed up) and Terry’s cowboy hat, and you know I never fit in. I don’t know why Philip picked that, I can only relate it to the accident, really.

How do you mean, never fit in?

Oh, being gay, being a writer, not having a nine-to-five job. In relation to my parents, it was a lot harder for me to be a writer than to be gay. It’s a lot harder for them to deal with my being a writer, especially a writer who has not sold his first hundred-thousand-dollar novel. You know, my mother listens to these radio shows all the time to get me advice—all these writers whose third-rate novels have sold twenty million copies telling how they actually did it. She wanted me to write about face-lifting! I said, “Look, you want to write about face-lifting, you write about face-lifting. I don’t want to write about face-lifting, I don’t write about those things.” The situation got worse when I started writing exclusively gay stuff ... I’m sorry I did, in a way, but I did and I’ll have to pull out of it. But there was a point where I was doing music reviews for the Voice, I was doing film reviews for Soho—I wasn’t doing gay stuff at all. And then I just got myself very, very involved with the gay stuff. And I started writing exclusively gay stuff and then I got the radio show. I was asked to do WBAI’s gay show. My father and mother didn’t want me to do it. The thing is, I had already promised the listeners that I was going to have my mother on my first show. My father wouldn’t allow that. Still, they had to deal with the fact that their son was doing a gay radio show, their son was a gay media person.

How did you feel about the show? Did it take time away from your work?

The problems got very complex: I had a number of friends from my CR group who were successful writers and who warned me about getting trapped in gay media, becoming typed as a gay writer. But since I could see a wealth of things to write about in the gay world, I wasn’t that concerned. I kept writing different record columns, even if they were for porn magazines. I was still listening to records and keeping in touch with criticism, which pays bills. I always had gigs from the time I met Philip, I always had regular monthly gigs to write. And given my rent—which when I met Phil was seventy-six dollars, which meant thirty-eight dollars apiece—it doesn’t take too many of these gigs to stay afloat. And when I couldn’t stay afloat, I would sell first editions or sell records or something. I just had a knowledge of all these crazy things, which I think freelance people have to have in order to survive being a freelancer.

How did your work affect your relationship?

Well, I made the terrible mistake of trying to write a novel contemporaneous to the facts, of trying to write a novel about my relationship with Philip.

Why did you do that?

It ... it just flowed. When I met Philip, we each read our pieces in class. This guy went bananas over my piece. It was like such an ego trip that I just turned it into a novel. If he likes that, he’s gonna looooove this! In fact, he loved parts and he hated parts. But I can’t take criticism for shit. I don’t think most creative people can ... The relationship was so dramatic from the beginning, it was just so filled with drama—I don’t know if it’s just we were very dramatic people, the fact that we both loved drama. My mother always accuses me of that. Of loving drama. That’s an accusation coming from my mother. The writer in me just saw all these possibilities. Plus I got ego food from my writing mentor, who sent me to an agent—agent number one. [laughs] I also wrote music. I was writing songs about the relationship.

How did Philip respond to the writing?

First of all, to get him to read it was a major chore. Because he’d try to find the lamest excuses not to have to read it. I need approval but I also need encouraging approval. Philip didn’t wait to get the feel of anything I was writing, a general overall thing. He would start, you know, he would start, and he was really very critical and that’s not what a writer needs until the final draft. And now I realize that. Now I won’t show anything to anyone until I’ve reached the final draft on it. Because it destroyed me. Plus he didn’t like some of my characterizations of him. And he would be upset. It got crazy. The novel got crazy. I’m still on the third draft, the third draft I did rough, because I didn’t like it. I was bored with the whole thing. I was getting schizophrenic—which is the novel, which is the alleged relationship?—it would drive me bananas.

In general, Philip didn’t respond in ways that gave you much support?

Well, whenever we had a major blowout, I would retreat. I didn’t fight. Now I’m a fighter. I didn’t fight then, at all. My weapon was retreat. I’d just get real silent and not say a word to him. That would freak him out completely, nothing worse than silence. That’s the deadliest weapon you can use with anyone. Eventually we would say that he took it for granted that I was a quality writer, the kind of quality we both liked in writing ... but in fact I needed that encouragement, desperately. I mean God ... you know, creative people need so-o-o-o-o much ego food, it’s unbelievable ... when I think of the ego food I need, and some of the gigs I’ve taken just to see my name in print, because I was working on a long piece and it took a while and I wasn’t getting ego food ... so you write these stupid things ... just to see your name in print in a different type size or something. [Laughter] Philip didn’t understand that ... and Philip also had so many needs of his own—I mean, God, he was 21 when I met him.

How about Philip’s job?

Okay, yeah I think he was working a straight gig, but I mean we both had the perspective on it so that I accepted it in him. I thought it was just a step for him, you know. He also had much more nine-to-five tendencies than I did ... I’ve tried to get a lot of nine-to-five jobs, I really have. I’ve tried for some of the most ridiculous jobs ... and there’s this whole song and dance about being overqualified ... and they are really afraid of people who have interesting credentials. They sort of want dreary kinds of people in corporate jobs. But I wanted one corporate job so badly. I wanted to earn twenty thousand dollars a year. It’s not like I lo-o-o-o-ve being poor—I don’t think anybody poor just loves being poor. But if you have anything that makes you individual ... I don’t even like being an individual. I’ve always tried to look and act like everyone else. I have worked so hard all my life trying to fit in. I have gone to the most outlandish lengths just to fit in ... and nevertheless I apparently don’t. Because I couldn’t get any of these goddamned Newsweek jobs—you know, the president’s twerpy daughter can get these jobs and me with my goddamned degrees and my writing experience, I cannot get a fucking job. You know ... so I, so I accepted the fact that I can’t get a job, and I do my freelance gigs ... but underneath it all I’m a very conservative person who would like a house and would like a lover and would like two dogs and two cars and all this shit, but I don’t know if it’s in the cards ... I really don’t. And that scares me that I don’t even know if it’s in the cards. You know, I, I, I get real depressed, like because—I don’t want to become a businessman and I’m very good at it—I’m very good at business ... I’m very good at buying things real cheap ... I have an interest in antiques and all that crap—you know, and like I have this dread—my great fear is that that’s what I’m going to turn into ... that I’m going to become like all these other frustrated people and turn to these professions not out of desire, but just because I didn’t make it ... I remember in high school all the drama teachers who were, like, failed actors and they were always so goddamned dramatic. Whether they were straight or gay, actors are actors, and failed actors are failed actors, and I didn’t want to be a failed writer, I guess, you know and like ... you try to reinforce yourself by going over all these great writers who were never published in their lifetime, you know, it’s not a question of me not being published in my own lifetime; it’s a question of so much crap coming out ... [long pause]

How about Philip’s work, his photography?

Oh, I pushed him to do it, I pushed him and pushed him and pushed—I loved his work. I didn’t like his garden scenes or anything like that, because the only pictures I like are pictures with people in them. Nothing works for me unless there are human images in it. And of course the only ones Philip liked were the ones with no human beings in them. [laughter] His favorite photos are the ones he took in Paris when he went there before he met me, of the Luxembourg Gardens or something like that, and I just found them boring. Then Philip started taking pictures of me, because he was my lover—lovers take pictures of each other. And I would take pictures of him and I wanted him to teach me how to use the camera, and he didn’t really want to teach me how to use a camera ... You know, he wasn’t a teacher. It’s as simple as that. I would try to go to museums and I wanted to learn from Philip because you get tired of playing a certain role, you want to learn from the person you’re with, and Philip would get into a very pedantic state of mind—and I would storm out of the museum ... But he taught me so much about emotional interaction—that sort of balanced off things. I taught him about everyday realities, like about shopping, and all these crazy things I knew how to do, even about appearance. Now his appearance is much more studied than mine is, but then it was the other way around. I ... I ... always like to think I sculptured him, you know like I created a Frankenstein. [laughter] I always say that. If it wasn’t for me he wouldn’t be involved in this whole ... uptown mentality ... he’s not really involved in it, he sort of has a perspective on it, but he’s ... [pause]

You respect his art?

Oh yeah, yeah, yeah ... we used to fight about hanging things up. I would hang some of his photos and he would rip them down, I would put them up—I would frame a drawing and make these mats. I would spend hours making these goddamned mats. I was a shitty mat-cutter anyway—but, you know, I really loved his drawing. But he wouldn’t even let—this is interesting—he wouldn’t even let me lo-o-o-ok at his photographs without him being there. He had to be sitting right next to me, for me to look at his drawings or his photographs ... and I thought, yeah, I thought this was looney. It’s like—why can’t I just look on my own? I mean that’s really when you look, is on your own. When you’re looking with somebody, especially with the artist there, it could make you a nervous wreck sitting there and you can almost hear him saying: What’s he thinking? What’s he thinking? You know ... so ... there was probably a lot of competition too.

How about Neil the cruiser [Photo 8].

Yeah. Neil is a real hot cruiser. Neil does it with the best of them. Neil knows all the forms; Neil knows all the games. Neil’s best on the street. Neil doesn’t do too well in bars. But on the streets I am real hot, ’cause I just know how to do it, and I’m real quick and I’m real blunt, and I don’t get turned down too often. That is like a big joke to me at this point.

My image had suddenly come into vogue, the image I’ve had now for what, ten years? I always refused to bend too much to what gay society was demanding of me. I had gone through that in ’65, and I just didn’t like it. Like wearing button-downs—it was ludicrous.

Now I did real well. You see that’s not a sexy photo to me now, but I guess it was then. It wasn’t even sexy then. I mean that’s not sexy the way Philip was, that photo of Philip is sexy [Photo 9]. That’s really Philip as a hustler.

Does that turn you on?

Yes. Well, yes and no, I mean, my hustler image in general is much more Italian, much more raunchy, much more mean.

That picture looks to me like he’s trying to ape the type of sexuality that you’re putting on.

He tried to do that every so often. I think he tried to do that because he thought I’d be attracted to it. ’Cause obviously if I was doing it, I’d be attracted to it. His attitude was, anything you did, you were also attracted to. Anything you did in bed, you also wanted done to you. He believes that.

To go back for a minute, what was the context of [Photo 5]?

Ah ... I had a friend named Frank from years ago. Now Frank was just a lovely Italian guy. I happen to think that all Italian guys are lovely on principle. But he was real down-home. He wasn’t intellectual but he had real street smarts. I really dig that. And also we were opposites. We never had an affair, really, but we fucked a couple of times. And he was living with a guy in Connecticut, this guy I wasn’t crazy about actually, from a farm or something. And Philip and I had one ménage with a friend and his lover. And I had the most wonderful time. The four of us were fucking; Philip had something like seven orgasms. Just about went out of his mind. Anyway, next morning we did this Monday-morning quarterbacking and Philip was freaked out of his mind. Absolutely. I couldn’t believe this was the same guy who had such a night, who had so many goddamn orgasms. I can’t have seven orgasms. I can have four maybe, but seven is a lot. And I said, “What’s the matter, Philip?” He said “They were more turned on to you than to me.” I didn’t believe it for a minute. It turned out he was right in a way; it was a little marginal, I mean everybody was fucking around, and my God! It just pinpointed a problem in Philip. I mean, okay, you start off saying all men are competitive, but Philip goes above and beyond that, at least in this relationship. In the beginning he did. And I’m competitive to a degree, but only when I feel my situation is really in danger. That happened later on. But at this point, Philip was real competitive and I couldn’t understand it, because he seemed to be having a good time—but he said he was real uptight. And this is somebody who was preaching all kinds of open relationships and being able to relate to people other than your lover and how it’s valuable and how monogamy sucks, or not so much sucks, but it’s not necessary. I don’t take the position that, philosophically, promiscuity is necessary, it’s just one of my own needs, ’cause I have never met anybody who satisfies me sexually completely.

Wait a minute. The first ménage was a real problem, because Philip was freaked out because he thought the guys were more attracted to you. Then you went up to Connecticut . . .

Then we went up to Connecticut, and I didn’t like the owner of the place from the start. He was real cold and efficient. You know he was butch, butch. And, uh, we eventually fucked and it was a disaster. And I turn around and I see Philip getting fucked by this guy and this guy has an unusually large cock and when I saw Philip being fucked by somebody else, I just—“That’s enough, we have to leave, Philip.” I was absolutely freaked out. Absolutely. I couldn’t believe I was freaked out. Just seeing Philip getting fucked blew my mind. Nobody fucks Philip but me, you know? Nobody does. I tried to be cool; I mean I’m the one who’s arranged the whole thing. I couldn’t get it off with Frank, I mean Frank and I were not relating, and I think this photo [Photo 5] was the next day. Philip and I went into the woods. We got undressed, it was real nice. And I’m not a woodsy type. But it was real nice. We just ran through the woods and we had sex and I asked Philip to pose the way I saw him, which is just like this, and that’s the way I’ll always see him.

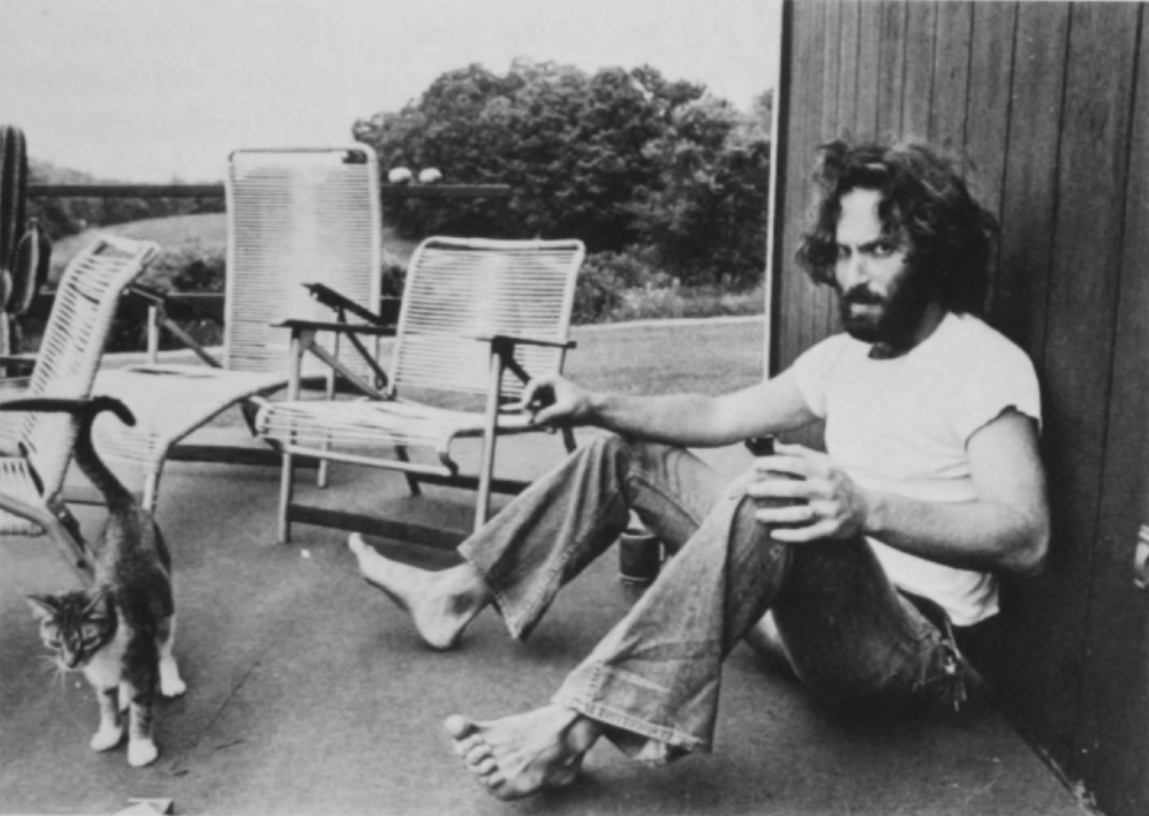

Okay let’s go on, do you want to discuss the picture [Photo 10] of you on the deck? The cat is going by, your feet are curled up.

Well I don’t like cats. I don’t remember the cat. I was really upset by that point. This was after we got back from the woods.

You were back together again, and you basically had overcome the problems from the night before?

Yeah, I think we had even agreed to leave earlier than we’d planned to, and that made me happy. I don’t know why I was so miserable. I couldn’t stand the guy we were with.

Because he told me that in the morning he’d woken up and he’d gone off to the other bedroom and had sex with this guy once again.

Oh that’s right. I just forget these things. That’s right, he did do that. I was so miserable. You know, I was so unhappy. And the only thing that made me happy was when we went to that flea market that day; I was real happy at the flea market. I just wanted to get out of there. We left that night. I was so miserable. I didn’t want to see him touched by anyone. Didn’t matter to me if he did it and I wasn’t there, but I was there and watched this. And it also wasn’t a ménage the way the four of us had the earlier ménage, always interchanging partners. I really felt the first time that communication was involved. The second time no, even Philip would probably indicate there was no communication involved. It was two people coupled off all the time. I mean Philip has this problem; let me tell you about Philip’s problem. One of Philip’s major problems is that he will experience something and enjoy it, and then the next day decide that maybe he didn’t really enjoy it. In his analysis I will not even recognize what happened half the time. We will discuss his sexual experience of the night before. Like our sex was not good. It wasn’t bad but it was not good.

What was your sex? Who did what to whom?

In the beginning it was pretty loose until he moved in. And then…

What do you mean pretty loose?

Well, we’d reverse position when fucking. And sometimes we weren’t fucking. Sometimes we’d get off other ways. He will never acknowledge that that was a key thing, but it was.

What was a key thing?

His moving in and this whole Monday-morning quarterbacking just made me feel very self-conscious about having sex ... The roots of my sexual problems with Philip go back to the kind of analysis I insisted on—my analyst helped me to relate to men only as sex objects, not emotional objects, not love objects. This was to get me in touch with women as both sex and love objects. It really was the kind of analysis…

Wait. Your shrink was saying it’s all right to sleep with men as long as it’s only for sex?

Right, exactly ... But this is what I wanted. I figured that when I got straight, I’d be a happy bisexual. But the fact of the matter was after a couple of years I was unhappily bisexual. Although I always had heavy emotional relationships with women, I didn’t really have good sexual relationships with women. They were just boring. I lusted after men; women were sexually boring to me at the time, so I stopped the analysis completely and came back to America. ’Cause I also stopped working. I had helped form a public-relations company in England, and after I formed it, I got bored ’cause public relations is really tedious, and I came back to this country. I mean, I was totally screwed up. I was totally screwed up because I was lusting after men but there was no way I could relate on any other level than sex, because I had trained myself not to see them as love objects. And I can’t say heterosexual society was dumping on me, because I made all these decisions. Therefore, I wasn’t bitter, really. I just knew I had to work this thing out. It took years and years and years—and I couldn’t afford analysis, I didn’t want to go back into analysis. I really had to train myself to see men as love objects, and take more and more chances with men sexually and otherwise. I wasn’t particularly in touch with sex when I was twenty-one, twenty-two. I just didn’t think about sex that much. I got off. I guess I would fuck guys; I certainly wouldn’t get fucked. And I had oral sex—I wasn’t really into oral sex the way one can get into oral sex.

I had a strange relationship with this American Indian guy—the loveliest guy I ever knew, the kindest, sweetest man I’ll ever meet, who fell in love with me and I didn’t fall in love with him. I just wanted somebody else to share things with, have a roommate. But he fell in love with me, and I warned him not to fall in love with me, but he fell in love with me. We lived together for six months in the same bed and did not have sex—I can’t even imagine how he dealt with it. At one point he started to throw china at me. I was living on Hudson Street in the Village. I wrote a play and a musical just to escape from him. Eventually I found a place by myself on Crosby Street.

This was right before Philip?

The American Indian? Not right before. I went to India in between this guy and Philip. I went to Greece for six months in between this guy and Philip. And I was a waiter and I sold political buttons. I had these schizy little jobs.

This all resulted from my analysis—my analysis had worked, in fact. Yes, this is why love objects couldn’t be sex objects. But I was working on it. You know, sort of getting closer to men and seeing them as love and sex objects, and being a little looser sexually but not really. And slowly but surely I saw this gradual progress, and much as I’m extremist in life, I was really pleased by this gradual process. I guess that’s maturity, accepting gradual progress as opposed to these really extreme kind of Bette Davis situations. I got into an experimental relationship with two guys and it was very hard. I felt I was a central focus, that these two guys didn’t like each other. I wanted us so badly to like each other and live together for a few weeks. Nothing more. This was a really bizarre relationship. This was sort of my experimental stage.

By the time I met Philip, I was real proud of myself. I had reached a level emotionally which I had never gotten to before.

I had come back a lot from my analysis. I had gotten back in touch with the fact that men were really my sex objects and my love objects. But at the same time I hadn’t really had to deal with any kind of primal relationship. I hadn’t had that in a while. I even had an affair with a woman at the same time I was living with the American Indian. To this day I don’t know how men deal with it. I just put my feelings for women in the closet. I just don’t think about it. It’s hard enough to deal with men, and at least men I know I can get it up for. And so by the time I got to have sex with Philip, it was all well and good until he moved in.

What happened when he moved in, in terms of the sex? Before he moved in you were basically both taking the active and passive roles alternately.

Yeah, well he was taking the active role but he didn’t like it, that was the ironic thing. I was forcing him to be active. Really. He was just out, he wasn’t really gay. I don’t think he’s gay now. A lot of people say this to Philip and he doesn’t quite understand or know how to deal with it, ’cause he sees himself as gay. I don’t see him as gay; I never did, and never will. But he’s Philip. That’s the only way, he’s Philip. Our sex got very routine. Sometimes it took a couple of hours and sometimes it took a couple of minutes. And he loved getting fucked; he loved it. And then one day he grew up and he decided he wanted to fuck as well, and to me it was just a process; I got him when he was in a process of growing. That’s how I see it. A lot of guys when they come out feel they should get fucked. And in a way there was a whole Greek element I think. I was the older, wiser. Yes, he was very in touch with feelings and all that, but his wisdom in dealing with me was lacking. He would throw truth around, and had no regard for my feelings about it. He would be devastating in very negative ways. Believe it or not, I see the relationship as the most positive thing that’s happened in my life. But there were some very heavy negative elements involved. He just went too far most of the time. He had me up against a wall, and you can’t relate when you have one party up against a wall. He was always setting up definitions for how we were gonna talk about our problems.

I want to get back to sex. So you basically were the active person. Did you ever take the passive role?

I felt too threatened. I was afraid of him at first, he was stronger than I was.

In what way?

Physically. He could beat the shit out of me. He’s real strong, physically strong. And I’m not. Now I am ’cause I’ve been working out. Then I wasn’t. I had other attributes. I cooked. I’m a good cook. I cooked up a storm for him. I didn’t cook for me. I didn’t eat. I cooked for him. After a while you’re standing there and you feel you’re like Alice in The Honeymooners.

I don’t think under normal conditions we would have related to each other. We would have seen each other as too powerful. But I think when you meet somebody in a classroom, or in a nonsexual setting, the relationship takes on very different contours than if you were in the baths or in a bar or something. It goes a very different route, I think a more healthy route. I think because I met him in a classroom, the whole thing was not so circumscribed by sex for me as it was for him. I think I was the first serious man in his life. He was the first serious man in my life. I’m basically a family man, there’s no way around it. I want somebody to be there all the time. It’s just too desolate to live alone.

Ever consider pets?

No. I’ve had two dogs. At one point I had two dogs, two rabbits, two finches, twelve old-world lizards—I mean you name it, I’ve had it.

To get back to sex.

My lizards are much more interesting than my sex life.

Who wanted more sex?

Oh he did. Jesus Christ. It’s like it was never enough for him. You know we’d have sex five times a week, he wanted it fifty.

He claimed I wasn’t in touch with anything. I probably wasn’t. But I never had a relationship with a man, so how the hell was I supposed to know what I was supposed to be in touch with? I accepted him…

Wait, wait, wait. You never had a relationship with a man?

Well, not so profound as with Philip. Philip and I had a very desperate relationship. We were both really shooting for the stars. And we reached the stars; but we also reached the pits. Oh God, Neil, you’re really getting tacky. Sex, let me think, sex.

He wanted more sex than you did.

It wasn’t just more, what he wanted was qualitatively different.

How do you mean?

He said I wasn’t tactile enough; he was very into touch. And I always felt that he was too genitally oriented. Like he turned everything into a genital situation as far as I was concerned. I couldn’t lie down with him without getting the sense that he wanted to fuck. I was not all that in touch with my sexuality when I met Philip. I guess I was considered hot sex for a night, but anybody can be hot sex for a night. That doesn’t take much. It takes much more to have sex five or six times a week, which later became two or three times a week, which later became one time a week, which later became nothing. You know. I agreed with Philip that our sex was too routine, but it was so based on what was going on in the relationship.

In a purely sexual setting, there’s no relationship to base anything on really, except the hour or two you talk to somebody. But in the relationship that goes on, the rest of the relationship ends up in bed with you. Everything that goes on in bed ends up in the relationship. And from the time I met him to the time he moved, Philip was working on a job that he hated. You know, he was working at a photography store and then he was working at Time-Life. Time Inc. goes against both our values very heavily. Who takes Time seriously? And what idiots work for that magazine and push that crap on everybody? Philip, that’s who! That’s who does it, Philip! You know, I didn’t taunt him about it because everybody’s got to earn a living and in this society, if you’re not working for a pig you’re very lucky. Philip was very resentful because I didn’t have to work regular hours. And I started getting published in the Voice sometimes. They were doing my music reviews. Until Clay Felker bought it. And then Soho News hired me as their film critic.

But not very well paid.

Well no, the Voice was paying like sixty-five dollars a review.

You think Philip felt resentment because you didn’t leave to go to a nine-to-five job?

Oh he told me he did. We were very blunt about our resentments toward each other, and that was nice, but he wasn’t too blunt about what he loved about me. That’s the irony. Yeah, he was very resentful of the fact that I didn’t work. Or that for instance, my aunt gave me a color TV because my black-and-white broke down. By hook or by crook I get what I want. I find jobs like reviewing, in which you get records for nothing—I’m obsessed with music and I’m obsessed with books. And I’m obsessed with people. So what do you need: you need records and books and people. And chicken’s pretty cheap. So you learn how to cook. Philip’s a little different. Philip’s upwardly mobile and he’s very into sophistication and very attracted to it.

After he moved out I saw some of the guys he was dating and I wasn’t particularly impressed because they were just a bit too sophisticated. They didn’t have the kind of values I adhere to, and they were very apolitical. I can see him dating a guy ’cause he had a nice car. But I’m impressed by certain credentials . . .

Discuss Photo 11.

All right, here was the problem I was talking about before, and that’s primal attraction. There are different theories on primal attraction. I believe that something makes you primally attracted to certain kinds of people. And I happen to be obsessed with dark people—Italians, Greeks, people I consider dark.

Philip, of course, is not dark.

Not at all. Although he could possibly pass for Italian. But it would be a very northern Italian. And Philip’s thighs I thought were real sexy. Like they were hairy and they were big. And I always dug thighs; I still do. But every time I looked at him he had so much longing in his eyes and I felt he wanted much more than I could possibly give him. I didn’t feel up to giving him everything, I just didn’t have it in me. I didn’t have the strength. I thought he was a laid-back Southern boy but it turned out he was a high-pressure New York Jew. Brilliant and everything else, and talented and beautiful, but very high-pressured. And so am I. Not so much. I’m probably more laid-back. And a lot more sensitive to other people’s feelings. He was totally insensitive to my feelings. No, strike totally. Not true. He was pretty insensitive to my feelings.

Why did you take that picture? You took it the same day as the nude picture, right?

Yes.

In Connecticut.

I think harping on that thing is a mistake. That was not the crux of our relationship. Philip happens to believe that unless something traumatic happens in which you prove your love, in a certain way it’s not real. Only when negative feedback happens in a relationship is the relationship valid. He so takes for granted all the positive things.

Philip thought you had enormous sexual power over him.

No, no, no, no, no. I didn’t have enormous sexual power over him. He created that power in his head. And the big difference is I didn’t experience the power. I only experienced the pressure. And the major bone of contention in our relationship was power, and I felt he had the sexual power because he was so able to respond to me sexually, twenty-four hours a day. I thought that was a great power he had, ’cause I was always intimidated by that.

But I got the impression that his demand for sex was...

Inordinate. There was a big power struggle in the relationship. My power was in the kitchen, in the culinary arts and shit like that.

And his power was where?

I don’t know if he had any... Well his power was sexual; not in that I was obsessed with sex with him, but I was guilty about it. I was obsessed with my guilt about our sexual relationship. The fact that he couldn’t understand how I could go out and trick when I wasn’t giving him the sex he wanted. He could never understand that. Philip could not understand that he was not my totality of experience, that I had other needs, fantasy needs. And I didn’t want to mix fantasy and reality with Philip. I was very clear on that. I knew exactly what I was doing. So it wasn’t as if I was stupid about it. I just didn’t want to mix fantasy and reality. I couldn’t picture myself talking dirty to Philip. I mean it was just ludicrous, I couldn’t. I couldn’t really think of doing any kind of “scene” with him. The one time we got even close to it was when we did poppers or we did something, and I got into a heavy aggressive trip with him. But I was freaked out for three days. I could not function for three days. And to treat Philip like that was disgusting. You see I had Philip on a pedestal. And when you have people on a pedestal, you can’t be too carnal with them.

Why’d you put Philip on a pedestal?

He was a god. Philip was a god, and he was physically, visually, a god. He also acted like a god, I mean I always felt inferior. Everything was real theoretical. Philip is a real theoretical person. And I was the exact opposite. I would always say, “Give me an example,” and he never gave me one fucking example of anything! Occasionally he pulled that trick on me and said, “Give me an example,” and I would give him six or seven examples of what I was talking about. And I don’t trust theory. He had so many theories, and every time he changed his mind about what the theory of our relationship was, I was supposed to go along with it.

You said that the power trip was a very important part of your relationship, and I’m curious. Putting him on a pedestal is a power play in a certain way.

Well, he had me on a pedestal too, so to speak. We were both on a pedestal. Yet we were both real, real, real, real. We were exceptionally real with each other. Not one stone lay, to this day, lies, unturned. All he can do with me, all I can do with him, is talk about the relationship. It’s like two historians getting together, two experts.

Once I was working in the London School of Economics in the British Foreign Office library and I met this guy studying “Somalia in January 1889,” and all he could talk about was Somalia. And that’s how I feel with Philip. All we can talk about is the three years of our relationship. We can’t go anywhere. And he admits certain things about our relationship that I was pushing for three years, but why can’t you admit it when it happens?

One of the reasons Philip refused to admit things was that he was younger, too; maybe that’s why. For instance, he would always contest things simply because I had said them. And the only person who does that in my life is my mother. Really. It’s amazing. Amazing. And I didn’t know when I got involved; I didn’t fall in love with my mother. ’Cause he was completely different then. That’s what’s so astonishing, just like a turnabout.

There were lots of power struggles going on in the relationship all the time. Everything we did, everything. I wanted him to start cooking and he would argue because he worked eight hours a day, but he wasn’t giving me the money. He always used this argument he worked eight hours a day, as if I was getting half of his money to cook for him, you know, like a wife. I said, “Look if you give me half your money, I will gladly cook. You don’t give me shit, you don’t give me a cent.” Finally one day I was broke. I was flat broke, and I said, “Philip, you’re going to have to support me, you know.” I was petrified because I’ve never been supported by anybody in my life. And Philip thought it was a wonderful idea, you know, real romantic. Okay, so what does he do? Every time I need thirty-five cents I had to go to him and ask him for the thirty-five cents. I was getting more and more freaked out.

Was that after you came back from France?

No... Yes. It was right after that. I was just broke. I had seen it coming, but I wasn’t really ready for it. And so now I depended on Philip. Now he had the power. And boy, did he misuse that power! You know, I said to him: “Well, why don’t you leave me thirty bucks?” He didn’t want to do it that way; he wanted to dole out dollar by dollar by dollar. So this went on for a month, then I just said forget it. I am not going to rely on you for money. And it really upset me, because he’s really bad with money. I’m not bad with money, actually. I was real lavish with him. And I didn’t care either. When I gave him a big birthday dinner, I spent three hundred dollars. I usually spend forty-six cents on my chicken but I really wanted to, and I spent about four days cooking. Four fucking days. I lived with Indians and Pakistanis and they taught me how to cook real Indian food, and so I cooked like ten different curries, really exotic. Advanced curry cooking. And like all of our friends were there, Philip was there, and it was really a wonderful thing, I thought. And I never quite got the feedback from Philip that I’d hoped I’d get. You know, he might have been a little overwhelmed by it. But it was very hard to get positive feedback. And he later claimed that he couldn’t really deal with how much he loved me because he was afraid of giving me more power. I just thought he was very difficult, that he was very quick with his negative feelings, but his positive feelings were real hard for him.

What was his reaction to this big birthday party?

... I don’t know. He liked it. He was freaked out by it. He was embarrassed. Everybody was paying attention to him. He was real embarrassed by it.

Philip doesn’t like attention?

I don’t know! He likes it until he gets it and then he doesn’t like it. He was very freaked out by it. I don’t think he understands what people see in him. And he never understood why I loved him.

Why did you love him?

I don’t know why. Turn the tape off for a minute.

...

The question was why you loved Philip. Do you want to talk any more about that dinner party?

I throw the best dinner parties. Ask anybody. I really do. It’s one big family. Everybody just stuffs themselves silly. There’s a lot of dope and good conversation. That’s all you need. And you don’t need room either. Everybody has the idea that you need room for a dinner party. You just have to have a table and know how to cook and know interesting people. And anybody can know interesting people if they’re interesting. Why did I love Philip? Philip was everything; he was my life. I wrote a book about him. Why do I love Philip? He was everything a human being should be. He’s so pure and, really, he’s so innocent. It’s unbelievable. Why do I love Philip? Jesus. Can we do that question later? That’s a really…

How about Photo 12?

That’s why I love Philip.

Philip in the cap.

Philip was so arrogant and so sexy and when I would see Philip at a distance, like on a street, I didn’t recognize him, really. I said, Who is that arrogant son of a bitch? Where does he come off walking like that? Then I realized it was Philip. I said, Jesus Christ! He really has this arrogant walk, which is not the Philip I know, really. I’m the only person who knows Philip, really. Nobody else knows him.

I think only children are arrogant. And if you meet somebody who’s fifty and arrogant, he’s just a child. And Philip was a child in our whole relationship, which was probably the problem.

He was so self-righteous. I always felt he was never asking me a question to get an answer. He was only asking a question so that I could say, “Well, what do you think, Philip?” and he would tell me the real answer. We would go through this process where he would ask me a question and I would give him what I felt was my answer and then he would go right around and tell me what he really thought I was saying. Nothing to do with what I was saying. And this happened all the time, day in and day out. I don’t know. I was happier then. I was. It’s like with all this shit I was so happy, I was so content. [long pause]

And we were very silly together; we had a whole language. I was Baby and he was Duck. He was Weiner Duck, he wasn’t just Duck, he was Weiner Duck. And whenever we didn’t want to deal with anything we just jumped into our baby talk.

Only when you didn’t want to deal ... ?

No, no, sometimes it was just a closeness. Like we were two kids together. In the beginning it was real nice, it was two kids playing with each other. But then we had discovered something that we could use when we just didn’t want to deal with the reality of the relationship, all the shit that went down and everything. And so then we just started using baby talk just at every excuse under the sun. We really became obsessive. Now it’s the only way we talk to each other. Not all the time, but it’s as if we cannot be real with each other now with our feelings. I mean I’ve just come through six months of a totally fucked-up stomach. I’m sleeping alone. I’m miserable. Now is that justice? I ask you, is that justice?

You expect justice?

Yes! I always expect justice, I never get it. I am desolate here. He’s in love. He’s not only not desolate, he’s in love. I’ll never forget what he said when he called me up two months ago. He said, “Neil, I don’t think I can ever fall in love again.” I said: “Oh, really Philip. Really now. Give yourself a little time. In a couple of years maybe we’ll both get over it and fall in love.” Sure enough, last Friday, he broke the news to me ... I owned him. I owned every inch of him. Every secret. It’s the little things, not the big things, the little things, the little secrets you tell each other. It’s waking up next to him, knowing his smell so well, incorporating him, thinking like him. That’s what it was. See, he wanted everything, he wanted to mold me. That’s what he wanted to do.

He wanted to mold you?

Yes, he wanted to mold me. I’m a rationalist, I guess. I see what somebody’s about and I weigh things all the time—is the good outweighing the bad?—and if it is, fine. I’ll accept the bad. But I accept the bad. He doesn’t, you see. He really wants God. And he wanted to mold me into the kind of image he had of me. Just somebody who’s like super-open and super in touch with all his feelings all the time. I mean part of his attraction to me was my distance. And he’ll never accept that. He thinks it’s all vulnerability, that’s what attracted him—that’s bullshit. I mean you know my physical image. That was always my physical image, like distance. I don’t perpetrate it, it’s just that I’m real uncomfortable with a crowd. Some people when they’re uncomfortable do certain things. I keep a distance. I look real unhappy, or mean. Not usually mean, just real unhappy, and most people don’t like that.

Did you have friends in common?

Oh, yeah. Well, I had a friendship of thirteen years, starting in seventh grade, and we both eventually came out and we were only gay together a couple of years, but we went through the sixties together. Philip hated this guy. By the time I had met Philip, I had also outgrown this guy. It started out, we were sort of surrogate lovers for ten years, we never had sex—we never discussed sex. We had a world of our own. We really did a whole trip together. And it was as close to a love affair as you can imagine, except there was no sex—there was a real bond, a real spiritual kinship. And Philip reacted violently to this guy. Everybody reacted violently to us together. The two of us had such a world of our own together over so many years, nobody could come near us. We were two kids in bliss; we had our own language. Phil hated him. It just so happened that I had seen myself really outdistancing this guy. When he came out, he went bananas, he went crazy gay. I didn’t go crazy gay. It was real gradual for me. So I had outgrown him, and Phil was a good excuse to break away. And in that sense I was glad that Philip was so adamant about not being around him. Philip really could not deal with him.

And then Philip and I were both in the Gay Academic Union, and I’d been told later that we were viewed as the model couple. For some reason gay academics don’t seem to have—or didn’t then have—a very high sexual self-image. Sort of dowdy and dull, scholarly. Philip and I weren’t like that at all. We were brash about our sexuality. We were intelligent, we were as intelligent as they were, certainly. We were real friendly; we had these dinner parties with them.

Also we had CR groups. Consciousness-raising groups which—everyone pooh-poohs them now—but they need it now more than ever. It’s so obvious—all over the place. And Phil was in one; I was in the other. So Philip formed all these bonds in his CR group and he bitched like hell to them—and he created an image of me. They hated me. They kept asking him why he was still in this relationship. Like, I had some mortal enemies in his CR group who under no circumstances was I going to allow in the apartment, even though Philip liked them a lot. So he had a couple of friends whom I disliked intensely. Because I knew they were against the relationship. They were threatening me and I didn’t like it. It was almost at the point where I was going to ask him to leave the CR group if it got too threatening. I watched his situation very carefully.

My CR group—we had an amazing CR group. It was like seven Jewish guys and one Italian who acted like a Jewish guy. In Phil’s CR group you could only ask questions of clarification. My CR group, you could give opinions. There were weeks I wouldn’t go in, I was so frightened to deal with some of those people. It got so heavy people would not show up at our CR group. It was a wonderful ... it went on for two years. Everybody was on the raft of the Medusa. That’s what it felt like, every week. It was an exciting, wonderful, important experience. And out of it, we moved in that circle—the politico-academic kind of circle.

And then there was Philip’s—did I have any friends?—there was Philip’s friend Susan from work, and I still have a very difficult time with her. She’s the most insightful woman I’ve ever met and I have enormous respect for her. And I even have very powerful love feelings for her. She was hot for Philip when she met him. Of course, I was a rival. We acted like rivals whenever the three of us were in public together. And Susan and I still have this love-hate, this push-pull thing for each other. So that was always a volatile relationship. I didn’t quite trust Susan, either. I saw Susan as a vulture. I really felt like a medieval knight. Protecting-my-fiefdom kind of thing: I have to protect what’s mine. If there are any threats to me, I’m going to take care of the situation. I will tell Philip who we can and who we can’t see. Depending on how threatening they are to me and how hostile they are to me.

Did you see a lot of friends? Did they constitute a society, a social context?