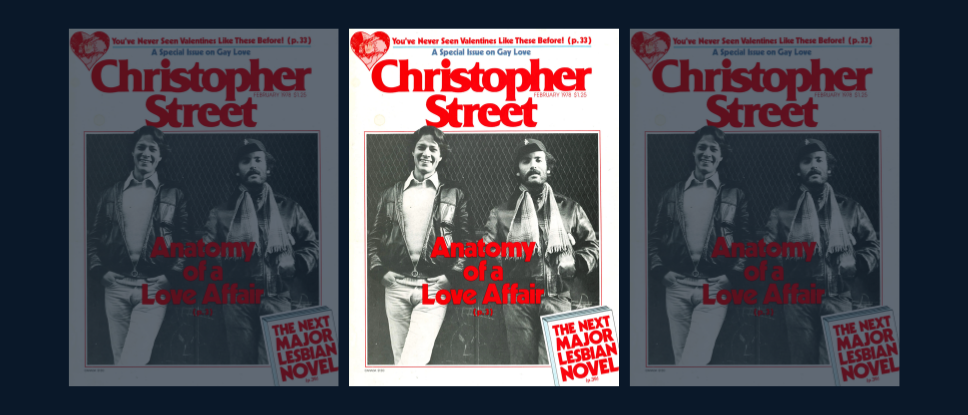

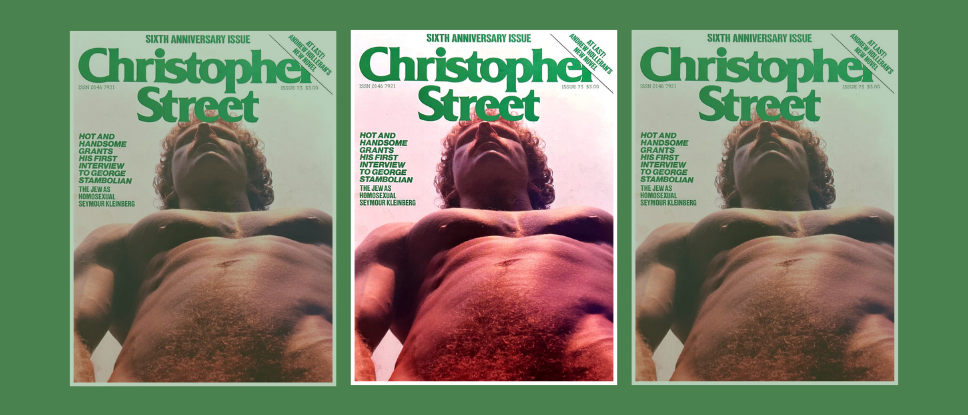

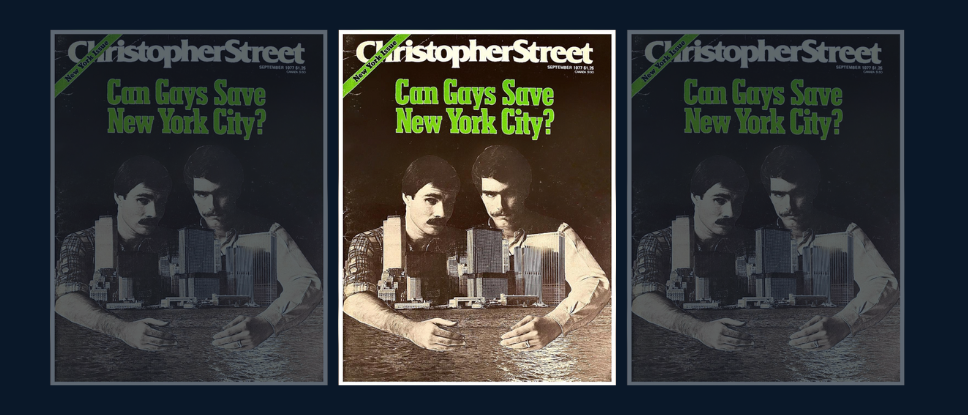

This article originally appeared in the February 1978 issue of Christopher Street on pages 1-2.

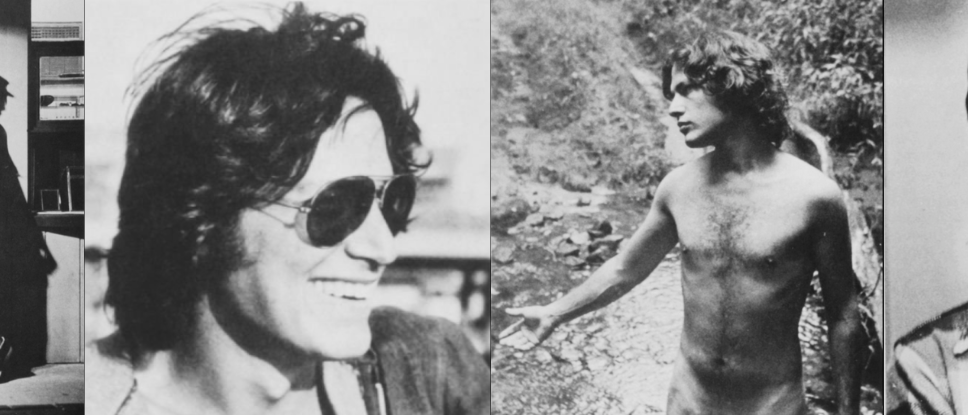

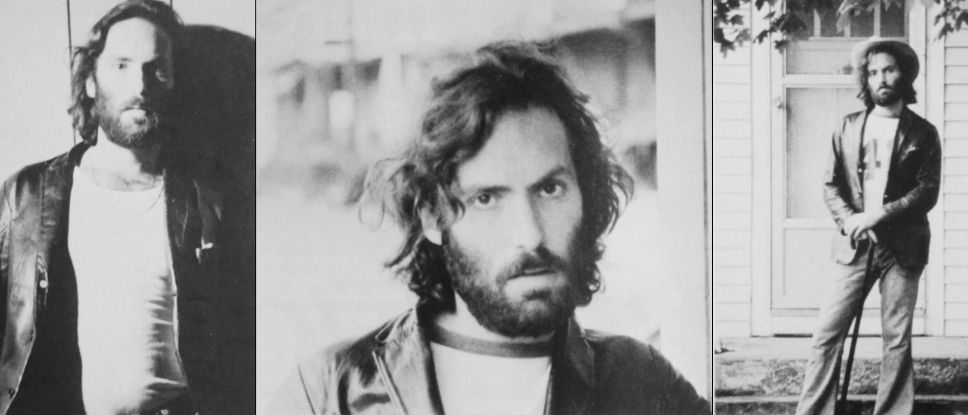

THE ORIGINAL IMPULSE behind this dual interview stemmed from the state I found myself in after three affairs ended “disastrously” within the same number of years. In this situation the mind has a tendency to play the game of “what if?”, to endlessly replay the same themes like a record caught in a groove, idiotically repeating one line—a psychological state caught with numbing precision by Kate Millett in Sita. I had become a burden to my friends and tedious to myself when I met Philip and Neil, whose own love affair had “ended” some six months earlier. I became intrigued by the fact that they had an unusual photo-documentation of the two and a half years of their love affair and even more intrigued to find out whether the themes of discord which had plagued me were totally idiosyncratic or whether they were the particularized expression of difficulties inherent in gay love, or perhaps in the loving of any other person.

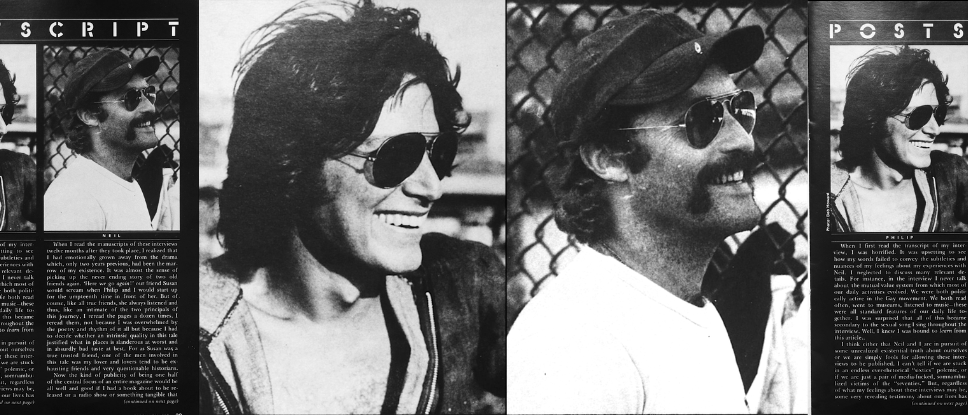

Using a selection of the photographs as a focus, I proceeded to interview each, separately, over a series of occasions; the hundreds of pages of transcript that resulted were then edited down to the present piece. These interviews were conducted under the pressure of strong and unresolved emotions, of late night hours slowly turning to dawn, of the urgency to understand what had happened and why. In the printed interviews I have tried to maintain the surface texture and rhythm of those intimate talks—the confusion and circling around a topic, the pauses and sentence fragments, the contradictions and sudden flashes of insight—for it seemed to me that the living texture of speech was as significant as what was said. This meant running the risk that Philip and Neil would sound less literate and more confused than is usually the case with printed whole sentences and clean paragraphs. This risk seemed insignificant compared to the larger question of whether it was appropriate to make such utterly private matters public.

“All happy families resemble one another,” said Tolstoy, “but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” And in this age of pop psychology and instant sociology, it is refreshing to remember that we read novels—stories of very particular individuals, not of the average person—and they are of some use to us. These are not interviews with a “representative gay couple,” if such should exist; they concern two very definite individuals. Like most individuals they are quite unlike the rest of us. Whether their story can be of use to the rest of us is for the reader to decide.

For my own part, I feel gratitude and honest admiration for their willingness to share this picture of themselves—for it is not their picture; inevitably it is my vision of them and their relationship, and there is no way I can maintain that I was merely a disinterested observer. Since they entrusted their self-presentation to me, I want to caution the reader to avoid hasty judgments. Neil says somewhere that he believes we are all made up of very profound and very superficial motivations and hate to admit the superficial ones—a notion I agree with. These two have been willing to expose both their profound emotions and their superficial feelings; their honesty should give us pause.

It is trite to remark that gay relations are uncharted territory, that none of us knows what we are doing. The following interviews are an attempt by two men to understand what happened to them. ❡