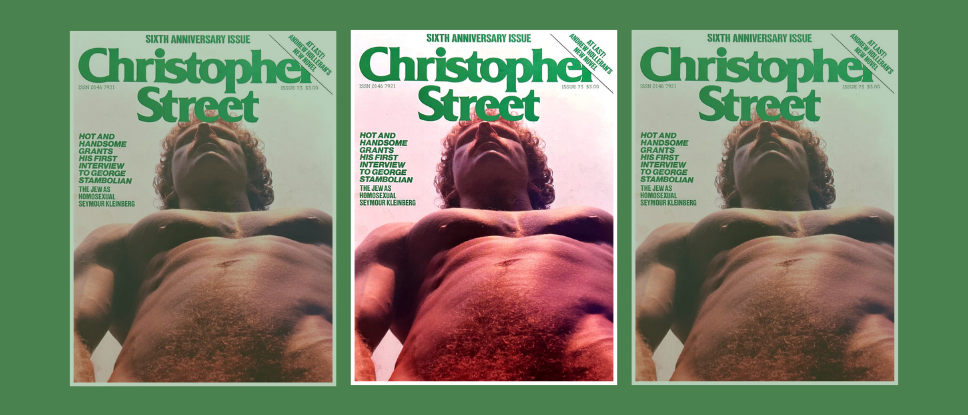

This article originally appeared in the July 1983 issue of Christopher Street, on pages 10-13.

“DON’T TELL ME,” a man standing at the window of a Fifth Avenue bookstore one afternoon this past October said to his friend as they peered at a display of Christmas gift books, “we have to go through this again.”

Yes, unfortunately you do, I wanted to turn and say to him as he straightened up and started walking northward in the warm autumn sunshine. I even wanted to stop him and give him my survivor’s guide to the three holidays that were hardly a month away—but I didn’t. I was too startled—not at the appearance of seasonal merchandise but a more fundamental fact: that Christmas is annual. For as we innocently walked toward Central Park that afternoon I sensed a vast tidal wave forming behind us: a tidal wave of custom, advertising, sentiment, and tribal rite which would crash down on Manhattan in about a month’s time and leave everyone drowning in debris composed in equal parts of Charles Dickens, the Gospels, and the Saks catalogue. I marvel at the holidays that come one after the other in such rapid succession—Thanksgiving (Bam!), Christmas (Pow!), and New Year’s (Biff!)—but have enjoyed them only since a friend gave me some advice one year about how to survive the trio: “The only way to be happy at this time of year, dear,” he said one day, “is to admit you are deeply depressed.”

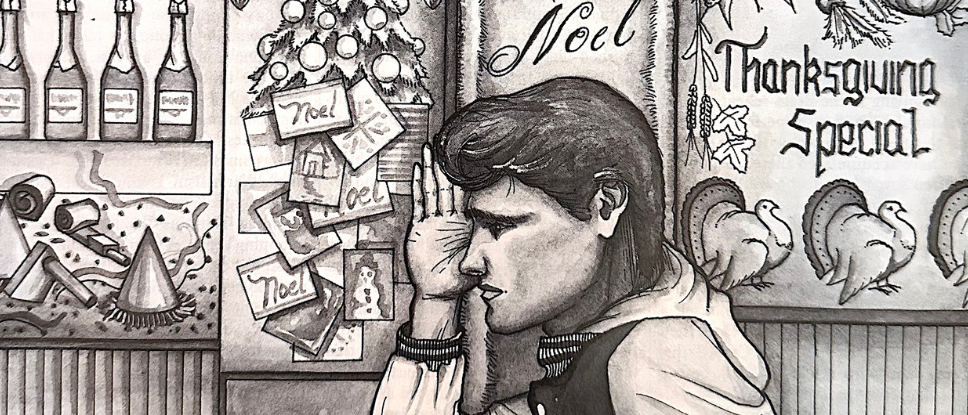

Even as children reading the Christmas cards our parents received by the bushel at this time of year, we suspected there was something odd afoot among adults. The cards were all so cheerful, filled with photographs of other children with their hair combed sitting in the family room so false. The family may have gone bankrupt, moved to another city to avoid the scandal of a divorce, or fought all year with a child who was misbehaving, but the note scribbled on the Christmas card said: “Dick and I had a marvelous trip to St. Maarten in February, the kids are doing fine, and we hope everything is all right with your family, too. Have a happy holiday!” A happy holiday is the last thing anyone was having; in those suburban homes which look so cheerful from the road, with candles in the windows and lighted eaves, under the mistletoe parents were learning that children back from sophomore year in college refuse to go to Mass anymore, have had an abortion, and don’t intend to return to school without a car. No wonder the New York Times runs an annual article—whether it appears under “Relationships” or “Science” or “Behavior”—that tells us family violence increases this time of year. Everyone is apparently depressed—no doubt because they are supposed to be happy—and the sudden compression of a reunited family home for the holidays produces pressures beyond the reach of Tums.

Those outside the house with a turkey in the oven, those who live alone in cities, have their own kind of depression to deal with, of course: that they are not home with people screaming at each other. They are instead walking back from their deserted gym through the grimy streets of lower Manhattan wondering where they will spend Thanksgiving (Bam!), Christmas (Pow!), and New Year’s (Biff!). First, will they have to go home to Baltimore? Second, if they do not, will Ed or Martin or Joe invite them to dinner? The whole thing may seem to an urban homosexual whose routine is suddenly interrupted like one big annoyance. Fighting the phenomenon—trying to make it gay—will not work. The stationery stores on Christopher Street all carry cards with muscular, half-naked Santas sitting on toilets, or holding their dicks, but these are not entirely persuasive. One may even consider going to the baths more frequently as a present to yourself, or tying a ribbon around someone under a tree, but in truth the pagan elements of this holiday—which precede Christendom—do not quite convince us, bombarded as we are by Dickens, St. John, and Monteverdi. It’s fun to look at the naked Santas on the greeting cards but one doesn’t send them—one sends Fra Angelico instead—and when it comes time to go to the baths around Christmas, I go less and less. What would I find when I got there? People hiding from Christmas, I always imagined. The strange pull this holiday has on us was the subject of a film made several years ago with Fannie Flagg, about folks in a gay bar on Christmas Eve. I never saw the movie, but got the idea. Even bars—above all, bars—do not hold up at this particular time of year. Admit it: you’re vulnerable.

And despite this, or because of this, I never want to stay in the city more—for half the angst at this time of year among homosexuals is in having to leave the city to go home. Home you feel is the city. It is not just hating to leave your friends, habits, life, but feeling you are being summoned back to a past, an identity, no longer yours, like an actor adopting a role he is sick of.

Thanksgiving is the dress rehearsal. This first family summons is perhaps the easiest to spend in town with the friends you have accumulated there. At home it is often something to be wary of: fending off, as you pass the mashed potatoes, the inevitable question, “Are you ever getting married?” One goes resentfully at best, so resentfully that for years a friend of mine faked his arrival in a certain Midwestern city to allow himself a few hours to slip into town before he expected him and visit the Club Baths, like a man who needed a drink before he could face the reporters. This was always at three o’clock on a mid-week afternoon, however, and there was seldom anyone there besides the man at the check-in counter. Over the years he slept with the manager, and the manager’s assistant, appearing once a year as seasonally as pumpkin pie. By the time he reached his thirties he was no longer able even to make the gesture of rejoining his family, and said he would visit them after the holidays when things were quieter. That way he avoided the annual party the neighbors gave at which he politely listened to stories of his married classmates and their broods, feeling vaguely like a vampire. There was a certain poignance he felt in not being nine years old anymore when he came home for the holidays. They wanted him home in any state—married or single, with or without kids of his own—but he felt odd. “I just wasn’t a small child anymore,” he said. “I was a large child.” So he dug in his heels, thought of the line of Barry Manilow’s song (“I wanna be somebody’s baby, don’t want a child of my own”) and said he couldn’t get a plane reservation. By the end of his thirties, when he told his parents he wasn’t coming home, he gave no reason; no reason was required; by that time they had conceded to him a life of his own. By the time he was in his forties, it didn’t matter anymore, and he went back home again with no complaints: friends.

Having survived Thanksgiving with or without these methods, he next had to gird himself for the grand-daddy of them all, however: Christmas. People complain justifiably that Christmas is nothing more than the climax of the retail year. They are right, perhaps, but the trouble is Christmas remains (incredibly, in view of the onslaught) an extraordinary emotional event. It commemorates essentially the birth of a distinguished child to a couple in a motel in Galilee; it is therefore a celebration of the family, a holiday which seems made primarily for small children. Christmas always reminds those who are not, for whatever reason, having children, that they are not, for whatever reason, having children. And if you are not a small child or the parent of a small child, then you may not feel quite right. The men on the Bowery being given Christmas dinner are more destitute but not more forlorn than people without families who can pay their rent. It is the feeling that no one should be homeless at this time of year—and that no one should be home alone. You see what we are dealing with; this time of year is charged with emotions no other time of year is.

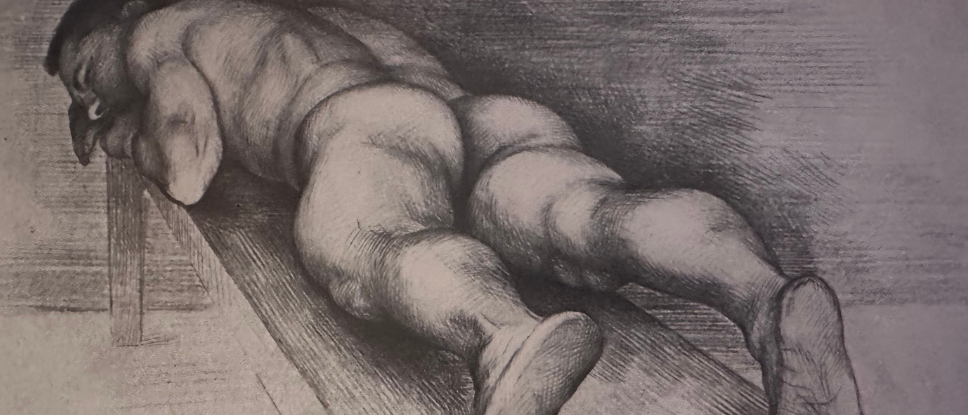

Which may be the reason bachelors not on the Bowery go to San Francisco or San Juan as the Eve approaches; in fact, if Christmas is too much for us then let’s go somewhere—till it’s over. Yet Manhattan is a fine place to be, I think, around the holidays. The little corkboards in the kitchens of those who remain in town are a mass of invitations to parties—never so many as at this time of year—and walking around the city one sees visions. The bongo drums have been replaced by a lighted tree in Washington Square, the skaters are twirling in Rockefeller Center, the lobbies of the big office buildings on Park Avenue are masses of poinsettias, and there is now if you are lucky as you stand peering at the teensy decorations in the windows of Tiffany’s or the toys at F.A.O. Schwarz. On Christmas Eve you have a boy’s choir in a church on Fifth Avenue or a pretty apartment with friends in bow ties looking at the latest issue of Mandate. (Be careful there. If it feels wildly inappropriate to be with nineteen men in an apartment on that evening—if this is too unlike one’s memories of Christmas spent with a family—then just don’t do it.) Always remember—at this time of year, when Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s hit us like three rapid blows to the head and heart, each with its own peculiar memories, customs, desire, and sadness, there is a river running underneath the city, a river that is powerful and deep. We are adrift on a flash flood of images which are all sentimental, familial, tender, and best handled by human beings eight years old. Little do the kids know what heartache Christmas causes among adults. Christmas is not gay. As its Eve approaches, the city seems like a vast playground from which everyone has taken his toys and gone home or at least indoors, except the mother yanking her small son into the last department store to finish her Christmas list. Most public life diminishes. One feels strange going to the gymnasium on December twenty-third. Narcissism is out. Real daddies, the average weightlifter thinks, are not pumping Nautilus machines; they are wrapping presents for their children.

And if the gym seems forlorn the closer one gets to Christmas Eve, one does not want to go into a bar much either, and the baths are utterly off-limits. I have seen people go into the baths on my block on Christmas Eve but I have never had the nerve myself. Christmas Eve is simply not like any other night; I admit it. The city stills as night approaches. The sidewalks empty. The town dies. When you walk across Ninth Street to have dinner at a friend’s or to go to the service at some church on lower Fifth Avenue, you are virtually alone, and the only sound is the hiss of some taxi’s tires turning onto Greenwich Avenue. I don’t want to see an attractive man on the sidewalk when I leave my apartment. I feel sexless on Christmas Eve. Eros withdraws for a moment. Agape takes over: comrades, friends, family, people you have not seen in a long time all occupy the mind. One floats in a warm solution of memory and the lighting is just right: the warm glow of those red and green bulbs on balconies and trees that were the color of Christmases of childhood.

People will always—as Mr. Sheed said—be kind, and they are never more so than at Christmastime. The friend who vowed he would not have people in this year cannot resist decorating his apartment with wreaths and evergreen, and does. If anything the worry is not being alone but the opposite. Don’t accept an invitation just to go out. Worse than being alone on Christmas Eve is to be with the wrong people. One year I found myself accidentally alone in town at the last minute; I was in limbo; I lighted a candle, read a story in The New Yorker by Nabokov, and went to bed with music on the radio, if not with visions of sugarplums dancing in my head, then the knowledge there was nothing to be afraid of in spending Christmas Eve alone. In fact it was a gentle opportunity to remember other people at that hour; for there is, when all is said and done, something curiously magical, tender, moving about the few hours before midnight on the night of December twenty-fourth. It extends its blessing to everyone on earth, alone or with others. I can’t account for it, but on that night the nastiness of the world is momentarily muffled.

But if you are afraid of its capacity to chill the solitary soul, you who would survive the season, keep one thing in mind as final comfort: on December twenty-sixth, it is over. On December twenty-sixth, you wake to find garbage blowing in the wind down Third Avenue and the local prostitutes on the corner. For the oddest thing about Christmas is that, as magical as it may be, the next day it is gone. The three weeks of increasing sentimentality have all gathered to an ooze and burst. What you have is a dishevelled city essentially normal again: a city still quiet, under an overcast sky, as grimy as the unshaven men standing inside the OTB parlor betting on horses or the lottery. Manhattan has the feeling of a house when everyone in pajamas sits down on wrapping paper and newspapers and eats fudge, gathering strength until it is time to go out to begin the arduous task of exchanging sweaters. The mood prevails until New Year’s in fact: the city may be open all week but it is lightly staffed.

Everyone is relaxed. What do you have to worry about now? New Year’s Eve.

But this is relatively easy, for you are moving already away from the supreme family holiday, toward a feast which is cocktails and Cole Porter. You have survived another Christmas. You can go back to the gym, the bars, the baths. The weather is usually mild and a genial lassitude pervades the metropolis. Santa and Christ no longer preside—a man in a dinner jacket, a woman in rhinestones are the seasonal gods. The skyline of Manhattan at night is perhaps the most elemental image we have of urban sophistication, in fact, and New Year’s Eve is about urban sophistication (even though at home my parents stay in, and toast each other at midnight, a solution that makes sense). But be careful: New Year’s is not without its sentimental undertow. It is a nod to mortality, passing friendships, success or failure. It is a time ideally to be with people one cares for, a moment to reflect, hope, congratulate or comfort, hug and be hugged. It is a time—in the early Seventies—when friends of mine always met their next boyfriend at a particular party a certain professor gave on Madison Avenue. (He still does; do go if you can; next to the Museum.) On the other hand, it can be a frenzied and harassed attempt to have a good time. If you are lucky, you might ring the New Year in as I always do, having changed parties at the wrong time: sitting in the subway, staring at two men sleeping on the seat beside you and four girls in pigtails blowing bubblegum across the aisle. It is dangerous to find oneself at midnight in a crowd of strangers bathed in sentimental warmth. Be careful of Thanksgiving and Christmas and New Year’s, and spend the next day on the phone reviewing the parties you did not attend, and planning a neutral day at the gym, movies, a friend’s apartment. Just be careful in general, because these are five weeks of mood and melancholy, and it is no wonder that a week after they are over, the man I heard ask in front of the bookstore if he had to repeat them again, finds himself sitting in a cold kitchen with the wind rattling the window and his head in his hands, depressed and exhausted, suddenly thinking that the only thing that will do now is to call the airlines and get a plane to a very hot and very empty and very quiet island where he can lie in the sun and bake, as still and warm as—odd, isn’t it, that the holidays make a perfectly nice man wish he were a lizard? ❡