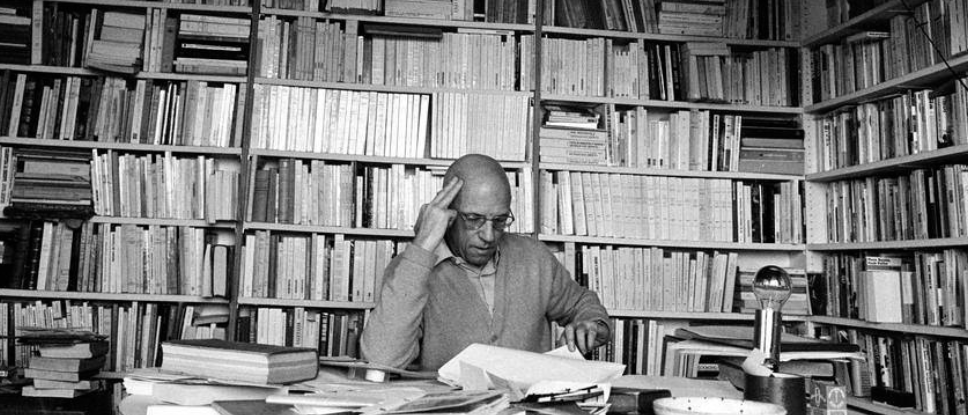

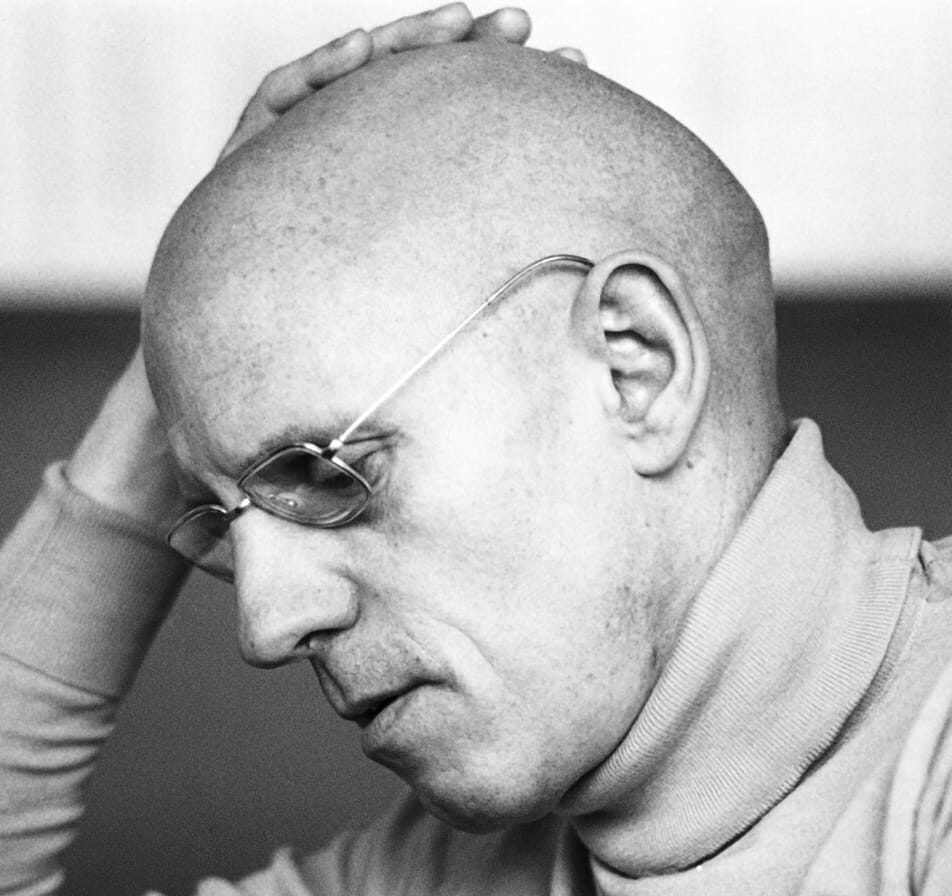

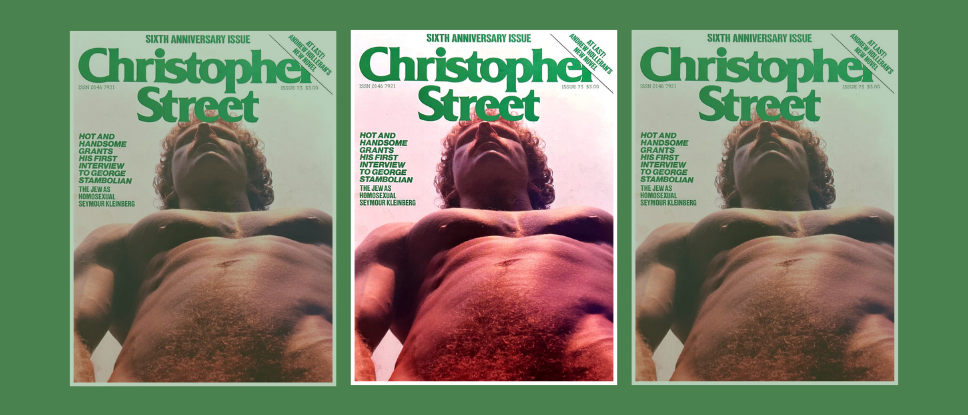

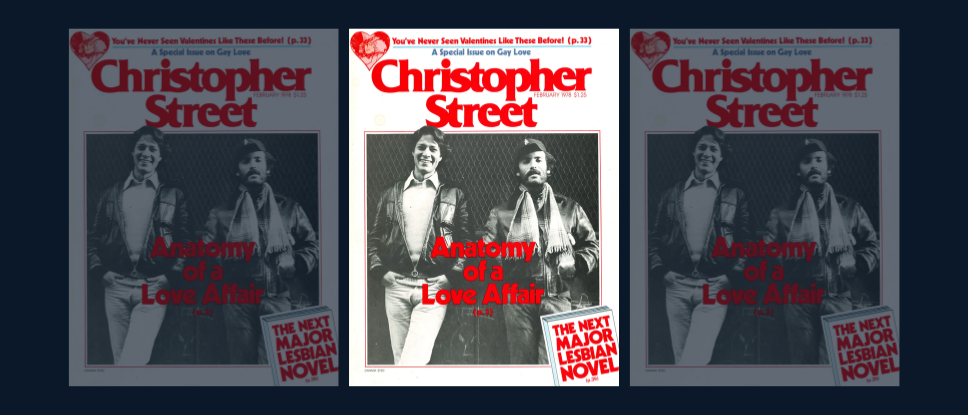

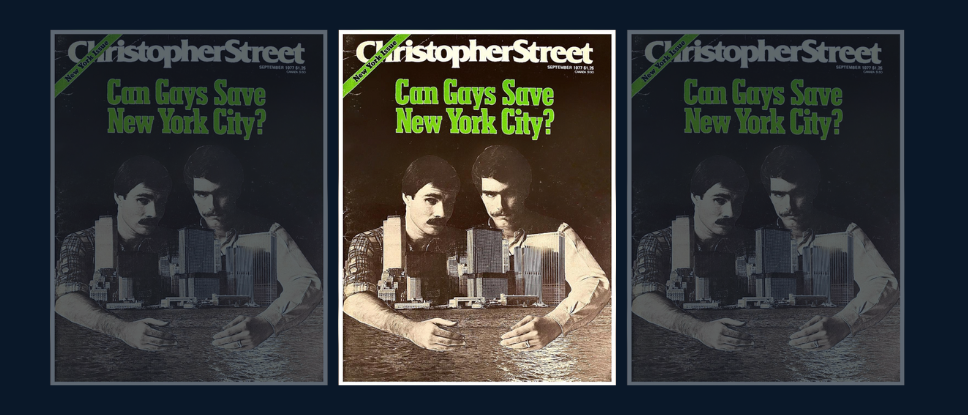

This article originally appeared in the May 1982 issue of Christopher Street, on pages 36-41, under the title "Conversation with Michel Foucault: Triumph of the Sexual Will." The interview was translated by Brendan Lemon and featured photographs by Richard Sennett.

Of all the countercultural and civil rights movements of the 1960s, there is one which seems to have carried over into the 1980s with little difficulty: the homosexual movement, and in a larger sense, gay culture. Why is the gay movement today more dynamic and more promising than the black or women’s movements in the United States, for example? The answer is certainly not found in the degree of solidarity or the degree of oppression, but in the invention by gays of a new relational culture.

For Michel Foucault, one of the most positive and striking traits of gay culture is its discussion of sexuality not only in terms of human rights or tolerance but in terms of existence and relationships. Moreover, by calling themselves gay, homosexuals have chosen to place sexuality elsewhere, outside the area traditionally assigned to sexual relations.

In one sense, the existence and direction of a gay way of life concerns more than gays because it involves or should involve a reworking of relationships within society so that the relations between individuals would no longer be limited by their validity with regard to classic structures of marriage or family.

Gilles Barbedette: Today we no longer speak of sexual liberation in vague terms; we speak of women’s rights, homosexual rights, gay rights, but we don’t know exactly what is meant by “rights” and “gay.” In countries where homosexuality as such is outlawed, everything is clear and everything is yet to be done; but in northern European countries where homosexuality is no longer officially punished, the future of gay rights is posed in different terms.

Michel Foucault: I think we should consider the battle for gay rights as a stage that cannot be the final stage. For two reasons: first because a right, in its real effects, is much more linked to attitudes and patterns of behavior than to legal formulations. There can be discrimination against homosexuals even if such discriminations are prohibited by law. It is therefore necessary to struggle to establish homosexual lifestyles, existential choices in which sexual relations with people of the same sex will be important. It’s not enough as part of a more general way of life, or in addition to it, to be permitted to make love with someone of the same sex. The fact of making love with someone of the same sex will naturally involve a whole series of choices, a whole way of life, and choices for which there are not yet real possibilities. It’s not only a matter of integrating this strange little practice of making love with someone of the same sex into pre-existing cultures; it’s a matter of constructing cultural forms.

But there are things in the course of daily life which obstruct the creation of these ways of living.

Yes, but that’s where there’s something new to be done. That in the name of respect for individual rights someone is allowed to do as he wants, great! But if what we want to do is create a new way of life, then the question of individual rights is not very pertinent. In effect, we live in a legal, social, and institutional world where the only relations possible are extremely few, extremely codified, and extremely poor. There is, of course, the fundamental relation of marriage, and the relations of family, but how many other relations should exist, should be able to find their codes not in institutions but in possible supports, which is not at all the case!

The essential question is that of supports, because the relations exist—or at least they try to exist. The problem comes because certain things are decided not by law-making bodies but by executive order. In Holland, certain legal changes have lessened the power of families and have permitted the individual to feel stronger in the relationships he wishes to form. For example, inheritance laws between people of the same sex not tied by blood are the same as those of a married heterosexual couple.

That’s an interesting example but it represents only a first step, because if you ask people to reproduce the marriage bond for their personal relationship to be recognized, the progress made is slight. We live in a relational world that institutions have considerably impoverished. Society and the institutions which frame it have limited the possibility of relationships because a rich relational world would be very complex to manage. We should fight against the shrinking of the relational fabric. We should secure recognition for relations of provisional coexistence, adoption…

Of children?

Or—why not?—of one adult by another. Why shouldn’t I adopt a friend who’s ten years younger than I am? And even if he’s ten years older? Rather than arguing that rights are fundamental and natural to the individual, we should try to imagine and create a new relational right which permits all possible types of relations to exist and not be prevented, blocked, or annulled by impoverished relational institutions.

More concretely, shouldn’t the legal, financial, and social advantages enjoyed by a married heterosexual couple be extended to all types of relationships? That’s an important practical question, isn’t it?

Certainly, but once again I think that’s hard work, though very, very interesting. Right now I’m fascinated by the Hellenistic and Roman world before Christianity. Take, for example, relations of friendship. They played an important part but there was a supple institutional framework for them—even if it was sometimes constraining—with a system of obligations, tasks, reciprocal duties, a hierarchy between friends, and so forth. I don’t think we should reproduce that model. But you can see how a system of supple and relatively codified relations could exist for a long time and support a certain number of important and stable relations that we now have great difficulty defining. When you read an account of two friends from the period, you always wonder what it really is. Did they make love together? Did they have common interests? No doubt it’s neither of those things—or both.

In western societies, the only notion upon which legislation is based is that of the Citizen, or of the Individual. How do we reconcile the desire to validate relations which have no legal sanction with a law-making body which affirms that all citizens have equal rights? There are still questions with no answers—that of the single person, for example.

Of course. The single person must be recognized as having relations with others that are quite different from those of a married couple, for example. We often say that the single person suffers from solitude because he is suspected of being an unsuccessful or rejected husband.

Or someone with “questionable morals.”

Yes, someone who couldn’t get married. When in reality the life of solitude is often the result of the poverty of possible relationships in our society, where institutions make insufficient and necessarily rare all relations that one could have with someone else and that could be intense, rich—even if they were provisional—even and especially if they took place outside the framework of marriage.

All that makes us foresee that the gay movement has a future which goes beyond gays themselves. In Holland it is surprising to see at what point gay rights interest more than homosexuals, because people want to direct their own lives and their relationships.

Yes, I think that there is an interesting part to play, one which fascinates me: the question of gay culture which not only includes novels written by or about pederasts—I mean pederasts in the large sense—a culture which furnishes ways of relating, types of existence, types of values, types of exchanges between individuals that are really new and are neither the same as, nor superimposed on, existing cultural forms. If that’s possible, then gay culture will be not only a culture of homosexuals for homosexuals. It would create relations that are, at certain points, transferable to heterosexuals. We have to reverse things a bit. Rather than saying what we said at one time: “Let’s try to reintroduce homosexuality into the general norm of social relations,” let’s say the reverse: “No! Let’s escape as much as possible from the type of relations which society proposes for us and try to create in the empty spaces where we are new relational possibilities.” By proposing that new relational right, we will see that non-homosexual people can enrich their lives by changing their own schema of relations.

The word “gay” itself is a catalyst which has the power to negate what the word “homosexuality” stood for.

That’s important because by getting away from the categorization “homosexuality-heterosexuality,” I think that gays have taken an important, interesting step; they define their problems differently by trying to create a culture that makes sense only in relation to a sexual experience and a type of relation which is their own. By taking the pleasure of sexual relations away from the area of sexual norms and categories and in so doing making the pleasure the crystallizing point of a new culture, I think that’s an interesting approach.

That’s what interests people, actually.

Today the important questions are no longer linked to the problem of repression, which doesn’t mean that there aren’t still many repressed people, and which above all doesn’t mean that we should overlook that and not struggle so that people stop being oppressed; but of course I don’t mean that. But the innovative direction we’re moving in is no longer the struggle against repression.

The development of what used to be called a “ghetto,” and which now consists of bars, cafes, and baths, has perhaps been a phenomenon as radical and innovative as the struggle against discriminatory legislation. Of course some people would say that the former would exist without the latter, and they’re probably right.

Yes, but I don’t think we should have an attitude toward the last ten or fifteen years which consist of stamping out the past as if it were a long error that we’re finally leaving behind. A lot of change has come about in behavior, and this took courage, but we should no longer have only one model of behavior and one set of problems.

The fact that bars have—for many—stopped being private clubs indicates what transformations are taking place in the way homosexuality is lived. The dramatic part of the phenomenon—making it exist—has become a relic.

Absolutely, but from another point of view, I think that’s due to the fact that we’ve reduced the guilt involved in making a very clear separation between the life of men and the life of women, the “monosexual” relation. With the universal condemnation of homosexuality, there was also a lessening of the monosexual relation—it was permitted only in places like prisons and army barracks. It’s curious to note that homosexuals were also uneasy about monosexuality.

How so?

For a while people were saying that when everyone started having homosexual relations that we could all finally have good relations with women.

Which was of course a fantasy.

That idea seemed to imply a difficulty in admitting that a monosexual relation was possible, and could be perfectly satisfying and compatible with relating to women—if we wanted that. That condemnation of monosexuality is disappearing and we see women also affirming their right and desire for monosexuality. We shouldn’t be afraid of that, even if it reminds us of college dorms, seminaries, army barracks, or prisons. We should acknowledge that “monosexuality” can be something rich.

In the 1960s the integration of the sexes was seen as the only civilized arrangement, and this created in effect a lot of hostility about “monosexual” groups like schools or private clubs.

We were right to condemn institutional monosexuality that was constricting, but the promise that we would love women as soon as we were no longer condemned for being gay was Utopian. And a Utopia in the dangerous sense, not because it promised good relations with women, but because it was at the expense of monosexual relations. In the often negative response some French people have toward certain types of American behavior, there is still that disapproval of monosexuality.

So occasionally we hear: “What? How can you approve of those macho models? You’re always with men, you have moustaches and leather jackets, you wear boots, what kind of masculine image is that?” Maybe in ten years we’ll laugh about it all. But I think in the schema of a man affirming himself as a man there is a movement toward redefining the monosexual relation. It consists of saying: “Yes, we spend our time with men, we have moustaches, and we kiss each other,” without one of the partners having to play the nelly, or the effeminate, fragile boy.

Thus, the criticism of the “machismo” of the new gay man is an attempt to make us feel guilty and is full of the same clichés that have plagued homosexuality up to now?

We have to admit this is all something very new and practically unknown in Western societies. The Greeks never admitted love between two adult men. We can certainly find allusions to the idea of love between young men, when they were soldiers, but not for any others.

This would be something absolutely new?

It’s one thing to be permitted sexual relations, but the very recognition by the individuals themselves of this type of relation, in the sense that they give them necessary and sufficient importance—that they acknowledge them and make them real—in order to invent other ways of life, yes, that’s new.

Why has the idea of a relational right, stemming from “gay rights,” come about first in Anglo-Saxon countries?

That’s linked to many things, certainly to the laws regarding sexuality in Latin countries. We see for the first time a negative aspect of the Greek heritage, the fact that the love of one man for another is only valid in the form of classic pederasty. We should also take into consideration another phenomenon: in countries which are largely Protestant, associative rights were much more developed for obvious religious reasons. I would add, however, that relational rights are not exactly associative rights—the latter are an advance of the late nineteenth century. The relational right is the right to gain recognition in an institutional sense for the relations of one individual for another individual that is not necessarily connected to the emergence of a group. It’s very different. It’s a question of imagining how the relation of two individuals can be validated by society and benefit from the same advantages as the relations—perfectly honorable—which are the only ones recognized: marriage and the family. ❡